2017

The Faroese National Costume II

Date Of Issue 02.10.2017

Date Of Issue 02.10.2017

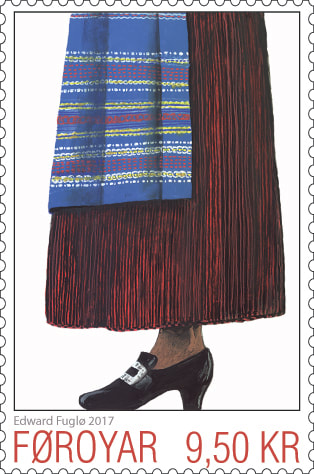

The Female Dress

The Skirt

Nowadays the traditional skirt is black with red stripes. The material used was the so-called "linsey", i.e. originally homespun flax with wool, but now machine-woven cotton with wool is being used. In recent years traditionalists have levelled some criticism at this trend. Young women especially have chosen other colours, for example black with green stripes or black with yellow stripes.

The sources, however, tell us that from times of old different colours have been used. In his description of the Faroes, dating back to 1800, pastor Jørgen Landt (1751 - 1804) reports that the skirts were brown with white stripes for everyday use and yellow-striped for special occasions. The tailor Hans Marius Debes (1888 - 1978) writes that formerly the skirts were dark blue in basic hue rather than black, with light blue, white, red, yellow or green stripes. Debes also writes that the skirt should be fitted with 13 pleats, the reason being the common practice of girls getting their skirts around the age of confirmation and as their bodies developed the pleats would gradually even out.

The Apron

The apron, of course, is a remnant of the old everyday dress and served the purpose of protecting the skirt from dirt and wear. It's easier to wash an apron than a skirt – and the apron can be replaced in a trice. Folklore researcher J. C. Svabo (1746-1824) stated that the aprons were made of blue-striped canvas, while H. M. Debes, a few centuries later, stated that they were made of muslin, silk or some similar fabric. In the past aprons were shorter than nowadays when they are worn exclusively for decorative purposes. Much attention is often paid to the apron’s embellishment, usually by using embroideries which, incidentally, have to match the scarf.

Socks and Shoes

Underneath the skirt girls and women wore black or gray socks, most likely knitted with Faroese yarn. Since then socks have become daintier, made of silk and nylon, and nowadays black nylon stockings or panty hoses are used.

The shoes were originally of traditional Faroese cowhide or sheepskin shoes, or clogs and galoshes. Besides, shoes of foreign origin have undoubtedly been used as well.

Today, the most commonly worn shoes are black semi-high heeled patent leather shoes with wide shoe buckles made of silver.

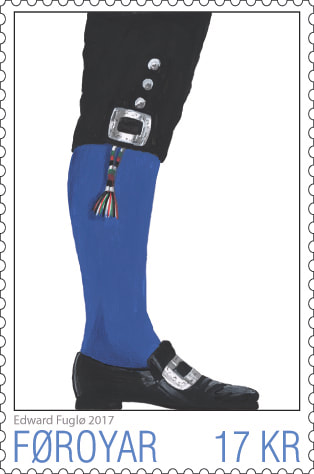

The Male Dress

The Breeches

One of the most distinctive features of the men's traditional costume are the black breeches. J. C. Svabo gives quite a humorous description of Faroese trousers used in his own times. He writes that they are black and wide, open below the knee and fastened about the leg with drawstrings. The fly was in front without any buttons, always open and extra visible because of the white undergarment. It would have been more befitting, in Svabo’s opinion, to use a flap or a panel to cover the front opening of the pants - but he doubted that this would happen.

Chances have actually happened since the times of Svabo. Today, the pants have a flap in front which is fastened up with silver buttons on the sides. The modern breeches are also tighter, made of black homespun cloth and they are also fitted with buttons in the seams just below the knees.

The reason for the traditional use of breeches is a practical one. Coming home after a hard day’s work it was easier to change socks than pants since work often meant getting your feet and legs wet.

The Stockings

The socks, or rather the stockings, are long, reaching up above the knee and held in place with a so-called garter, preferably woven in coloured patterns. The stockings date back to ancient times, most often brown or grey in colour. On festive occasions men often used blue or white stockings - which is also the case today. The stockings are usually blue, but they can be white or brown as well.

Footwear

Traditionally, cowhide or sheepskin shoes with long laces wrapped up around the legs were used almost exclusively. For festive occasions some men may have worn shoes of foreign make, but this would have been very rare.

As the national costume became distinct from everyday clothing in the late 1800’s, people started using "Danish shoes" which were more refined leather or patent leather shoes with a wide silver buckles, often decorated with shaded ornaments.

The Skirt

Nowadays the traditional skirt is black with red stripes. The material used was the so-called "linsey", i.e. originally homespun flax with wool, but now machine-woven cotton with wool is being used. In recent years traditionalists have levelled some criticism at this trend. Young women especially have chosen other colours, for example black with green stripes or black with yellow stripes.

The sources, however, tell us that from times of old different colours have been used. In his description of the Faroes, dating back to 1800, pastor Jørgen Landt (1751 - 1804) reports that the skirts were brown with white stripes for everyday use and yellow-striped for special occasions. The tailor Hans Marius Debes (1888 - 1978) writes that formerly the skirts were dark blue in basic hue rather than black, with light blue, white, red, yellow or green stripes. Debes also writes that the skirt should be fitted with 13 pleats, the reason being the common practice of girls getting their skirts around the age of confirmation and as their bodies developed the pleats would gradually even out.

The Apron

The apron, of course, is a remnant of the old everyday dress and served the purpose of protecting the skirt from dirt and wear. It's easier to wash an apron than a skirt – and the apron can be replaced in a trice. Folklore researcher J. C. Svabo (1746-1824) stated that the aprons were made of blue-striped canvas, while H. M. Debes, a few centuries later, stated that they were made of muslin, silk or some similar fabric. In the past aprons were shorter than nowadays when they are worn exclusively for decorative purposes. Much attention is often paid to the apron’s embellishment, usually by using embroideries which, incidentally, have to match the scarf.

Socks and Shoes

Underneath the skirt girls and women wore black or gray socks, most likely knitted with Faroese yarn. Since then socks have become daintier, made of silk and nylon, and nowadays black nylon stockings or panty hoses are used.

The shoes were originally of traditional Faroese cowhide or sheepskin shoes, or clogs and galoshes. Besides, shoes of foreign origin have undoubtedly been used as well.

Today, the most commonly worn shoes are black semi-high heeled patent leather shoes with wide shoe buckles made of silver.

The Male Dress

The Breeches

One of the most distinctive features of the men's traditional costume are the black breeches. J. C. Svabo gives quite a humorous description of Faroese trousers used in his own times. He writes that they are black and wide, open below the knee and fastened about the leg with drawstrings. The fly was in front without any buttons, always open and extra visible because of the white undergarment. It would have been more befitting, in Svabo’s opinion, to use a flap or a panel to cover the front opening of the pants - but he doubted that this would happen.

Chances have actually happened since the times of Svabo. Today, the pants have a flap in front which is fastened up with silver buttons on the sides. The modern breeches are also tighter, made of black homespun cloth and they are also fitted with buttons in the seams just below the knees.

The reason for the traditional use of breeches is a practical one. Coming home after a hard day’s work it was easier to change socks than pants since work often meant getting your feet and legs wet.

The Stockings

The socks, or rather the stockings, are long, reaching up above the knee and held in place with a so-called garter, preferably woven in coloured patterns. The stockings date back to ancient times, most often brown or grey in colour. On festive occasions men often used blue or white stockings - which is also the case today. The stockings are usually blue, but they can be white or brown as well.

Footwear

Traditionally, cowhide or sheepskin shoes with long laces wrapped up around the legs were used almost exclusively. For festive occasions some men may have worn shoes of foreign make, but this would have been very rare.

As the national costume became distinct from everyday clothing in the late 1800’s, people started using "Danish shoes" which were more refined leather or patent leather shoes with a wide silver buckles, often decorated with shaded ornaments.

Natural Dye

Date Of Issue 27.02.2017

Date Of Issue 27.02.2017

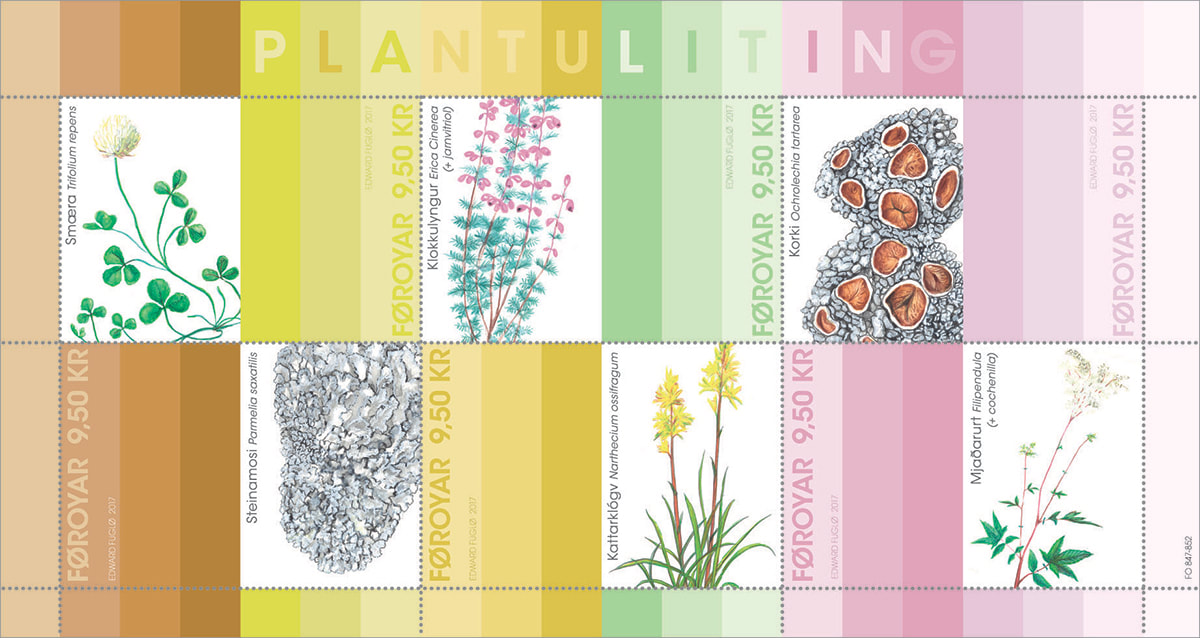

Natural Dye

One of mankind’s most distinctive features is that we are able to change and improve our appearance. This characteristic has a multitude of quite different expressions, most of which have to do with our clothes, the materials, design and colours.

From archaeological excavations in Europe, we know that the Neanderthal and Cro Magnon cultures used ocher, among other things, to sprinkle on the dead. Later, about 17,000-15,000 years ago, our distant ancestors used variants of ocher, colouring the cave paintings in France and Spain. Along with colourful jewelry of various natural materials and minerals, we assume that our ancestors used colours, first for body decorations, then decorations on clothes and dyeing.

Dyeing of clothes, as we know it today, has its origin thousands of years ago. Given that we started to manufacture textiles from natural materials, which in itself has different shades of natural colours, it was not a long step to dye the spun yarn or woven clothes.

Even in the Faroe Islands, home-dyeing of wool and clothes was a common practice. It was mostly natural dyeing with local plants, but later on people also imported dyes like for instance Cochineal, a sessile parasite that lives on cacti in South America, for bright red – and indigo for the bright blue colours.

Natural dye from plants does not give bright colours, but enough to make it worthwhile. On the stamp sheet, the artist Edward Fuglø presents some colour examples based on the book ”Plantuliting” (Plant Dyeing), written by the handicraft teacher and weaver, Katrina Østerø, known as Katrina av Trøllanesi, born in 1897. Katrina was especially interested in wool dyeing – and besides her own knowledge and experiences on the subject, she also collected recipes from other women on the Faroe Islands.

The colour samples on the stamps are :

Smæra – White Clover (Trifolium repens), which give pale yellow hues.

Klokkulyngur – Bell Heather (Erica cinerea), which gives light green hues.

Korki – Ochrolechia (Ochrolechia tartarea), a lichen that grows on rocks and stones and gives purple hues.

Steinamosi – Salted Shield Lichen or Crottle (Parmelia saxatilis), also a lichen that grows on rocks and stones, which gives brownish hues.

Kattarklógv – Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum), gives more dusty yellow hues than White Clover.

Mjaðarurt – Meadowsweet or Mead Wort (Filipendura ulmaria), which gives a slightly brighter purple than the Ochrolechia.

The Dye Process

The process of plant dyeing was largely this: The plants were washed and soaked for a day. If it was heather, it was cut into pieces before soaking. Then the plants were boiled for an hour in the same water (one to three hours in case of heather or bryophytes). Then the water was sieved and the liquor set to cool. When it had cooled down to 35 degrees Celsius, the wool yarn was put into the dye and boiled for another hour. After that, the wool yarn had to stand in the liquor for a day, after which it was washed several times, first in cold water, then in a mild soap solution and then again in clean water. The yarn should then be left in the last rinse water for a few hours, before it was taken up and dried.

Red and Blue

As mentioned before, there were no natural dye in the Faroes for the bright red and blue colours. Instead red was dyed with imported cochineal. The process was virtually the same as described above – one should, however, consider that the clothes could shrink when dyed with cochineal.

There are no indications of blue dye in the Faroes before indigo was available for import. The dye required a special approach, which most people probably did not care for, namely a lye of fermented urine. We shall not describe the process here as it is slightly off topic, but the price for the beautiful blue colour is said to have been a rather nasty smell of urine, which was difficult to wash out of the clothes again.

One of mankind’s most distinctive features is that we are able to change and improve our appearance. This characteristic has a multitude of quite different expressions, most of which have to do with our clothes, the materials, design and colours.

From archaeological excavations in Europe, we know that the Neanderthal and Cro Magnon cultures used ocher, among other things, to sprinkle on the dead. Later, about 17,000-15,000 years ago, our distant ancestors used variants of ocher, colouring the cave paintings in France and Spain. Along with colourful jewelry of various natural materials and minerals, we assume that our ancestors used colours, first for body decorations, then decorations on clothes and dyeing.

Dyeing of clothes, as we know it today, has its origin thousands of years ago. Given that we started to manufacture textiles from natural materials, which in itself has different shades of natural colours, it was not a long step to dye the spun yarn or woven clothes.

Even in the Faroe Islands, home-dyeing of wool and clothes was a common practice. It was mostly natural dyeing with local plants, but later on people also imported dyes like for instance Cochineal, a sessile parasite that lives on cacti in South America, for bright red – and indigo for the bright blue colours.

Natural dye from plants does not give bright colours, but enough to make it worthwhile. On the stamp sheet, the artist Edward Fuglø presents some colour examples based on the book ”Plantuliting” (Plant Dyeing), written by the handicraft teacher and weaver, Katrina Østerø, known as Katrina av Trøllanesi, born in 1897. Katrina was especially interested in wool dyeing – and besides her own knowledge and experiences on the subject, she also collected recipes from other women on the Faroe Islands.

The colour samples on the stamps are :

Smæra – White Clover (Trifolium repens), which give pale yellow hues.

Klokkulyngur – Bell Heather (Erica cinerea), which gives light green hues.

Korki – Ochrolechia (Ochrolechia tartarea), a lichen that grows on rocks and stones and gives purple hues.

Steinamosi – Salted Shield Lichen or Crottle (Parmelia saxatilis), also a lichen that grows on rocks and stones, which gives brownish hues.

Kattarklógv – Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum), gives more dusty yellow hues than White Clover.

Mjaðarurt – Meadowsweet or Mead Wort (Filipendura ulmaria), which gives a slightly brighter purple than the Ochrolechia.

The Dye Process

The process of plant dyeing was largely this: The plants were washed and soaked for a day. If it was heather, it was cut into pieces before soaking. Then the plants were boiled for an hour in the same water (one to three hours in case of heather or bryophytes). Then the water was sieved and the liquor set to cool. When it had cooled down to 35 degrees Celsius, the wool yarn was put into the dye and boiled for another hour. After that, the wool yarn had to stand in the liquor for a day, after which it was washed several times, first in cold water, then in a mild soap solution and then again in clean water. The yarn should then be left in the last rinse water for a few hours, before it was taken up and dried.

Red and Blue

As mentioned before, there were no natural dye in the Faroes for the bright red and blue colours. Instead red was dyed with imported cochineal. The process was virtually the same as described above – one should, however, consider that the clothes could shrink when dyed with cochineal.

There are no indications of blue dye in the Faroes before indigo was available for import. The dye required a special approach, which most people probably did not care for, namely a lye of fermented urine. We shall not describe the process here as it is slightly off topic, but the price for the beautiful blue colour is said to have been a rather nasty smell of urine, which was difficult to wash out of the clothes again.

The Eider

Date Of Issue 27.02.2017

Date Of Issue 27.02.2017

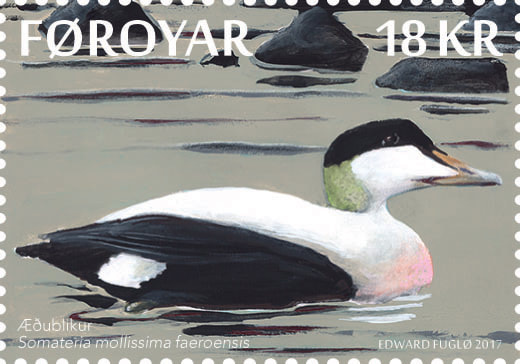

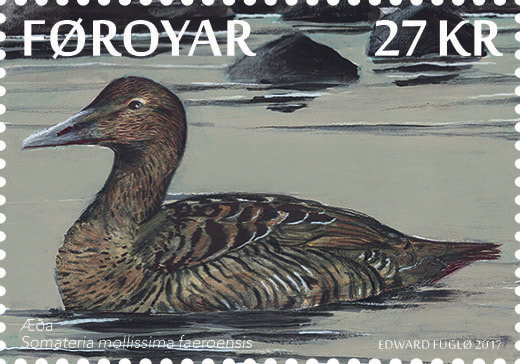

The Eider

The Faroes are a seabird country. Magnificent bird cliffs where fulmars, guillemots and similar birds whirl before landing on narrow ledges, provide excellent and dramatic images. This is the country of puffins with grassy hillsides sloping towards the sea, where clumsy but charming puffins dig their holes - or the Mykines islet which in summer is white with large nesting gannets – these images describes almost perfectly the outside world’s view of Faroese nature.

It is therefore no wonder that viewers tends to overlook one of the most common bird in the islands. Everywhere, in the fjords along the coasts and in port facilities, you will see large and small flocks of eiders gently swaying on the waves in all kinds of weather - the males in their beautiful black and white pairing suits, with a hint of pale green at the back of their cheeks and neck, sometimes with a touch of pale red on the chest, and the females with their discrete gaudy plumage in light and dark shades of brown, the perfect camouflage when they hatch in nests.

The Faroese eider is a subspecies of Somateria mollissima (Somateria mollissima faeroensis), found only in the Faroe Islands. It is a non-migratory bird, seen along coastal areas in the islands all year round, being the Faroes’ most widespread and largest wild duck (size up to 58 cm).

The eider’s hatching period stretches from the end of April until early September. Due to its relatively docile nature, it most often builds its nest by the shore – while sometimes also laying its egg in the outfield. Generally, however, the eiders brood in colonies, so-called “varp” where they are better protected against predatory birds. The nest consists of torn grass and moss, and when the female has laid its 4-5 eggs, it lines them with down, plucking it from its breast. When the parent bird leaves the nest to forage, it covers the eggs with down to keep them warm.

Traditionally eider down has been a valuable resource, being used as stuffing in duvets. In some areas of the islands islets and skerries where eider brooded have been protected in order to reap the down. It helped that the eider is unusually tame - there are stories of reapers effortlessly lifting the bird from the nest, gathering the down and putting the bird back on the eggs, causing no further drama. The eider then plucks its breast, wadding the nest anew.

As soon as the young are hatched, they are ready for life at sea and leave the nest with their mother. Eiders and their young gather in flocks along the coasts where they feed on isopods (Idotea), crustaceans, small crabs and fish. The eider is an excellent swimmer and can dive to a depth of between 3 and 20 meters. The adult eider may seem rather ungainly in flight, flying low above sea level, sometimes touching the water with its feet in order to pick up speed. However, I know from personal experience that the eider can fly with an impressive speed. Years ago I was driving along the coast of Skálafjørður, where an eider took off from the water and flew a few kilometers parallel to the car. All the way it kept pace with vehicle at a speed of 80 km per hour, using only a few meters to land next to another eider.

In summer, the males lose their splendid plumage for a short period and start looking more like the females. But at the end of the summer, they regain their colourful plumage. You will then be able to distinguish between the sexes as the chest of the young males gradually becomes white.

As stated above, the Faroese eider is a sedentary bird found in the Faroes all year round. It has no need of migrating to warmer countries since the warm Gulf Stream keeps the waters along the coasts at a fairly constant temperature. You will therefore be able to see this beautiful bird in all seasons. Even in stormy weather flocks of eiders can be seen swaying in turbulent seas, almost as a symbol of the calm, almost phlegmatic temperament needed to survive out here in the powerful grips of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Faroes are a seabird country. Magnificent bird cliffs where fulmars, guillemots and similar birds whirl before landing on narrow ledges, provide excellent and dramatic images. This is the country of puffins with grassy hillsides sloping towards the sea, where clumsy but charming puffins dig their holes - or the Mykines islet which in summer is white with large nesting gannets – these images describes almost perfectly the outside world’s view of Faroese nature.

It is therefore no wonder that viewers tends to overlook one of the most common bird in the islands. Everywhere, in the fjords along the coasts and in port facilities, you will see large and small flocks of eiders gently swaying on the waves in all kinds of weather - the males in their beautiful black and white pairing suits, with a hint of pale green at the back of their cheeks and neck, sometimes with a touch of pale red on the chest, and the females with their discrete gaudy plumage in light and dark shades of brown, the perfect camouflage when they hatch in nests.

The Faroese eider is a subspecies of Somateria mollissima (Somateria mollissima faeroensis), found only in the Faroe Islands. It is a non-migratory bird, seen along coastal areas in the islands all year round, being the Faroes’ most widespread and largest wild duck (size up to 58 cm).

The eider’s hatching period stretches from the end of April until early September. Due to its relatively docile nature, it most often builds its nest by the shore – while sometimes also laying its egg in the outfield. Generally, however, the eiders brood in colonies, so-called “varp” where they are better protected against predatory birds. The nest consists of torn grass and moss, and when the female has laid its 4-5 eggs, it lines them with down, plucking it from its breast. When the parent bird leaves the nest to forage, it covers the eggs with down to keep them warm.

Traditionally eider down has been a valuable resource, being used as stuffing in duvets. In some areas of the islands islets and skerries where eider brooded have been protected in order to reap the down. It helped that the eider is unusually tame - there are stories of reapers effortlessly lifting the bird from the nest, gathering the down and putting the bird back on the eggs, causing no further drama. The eider then plucks its breast, wadding the nest anew.

As soon as the young are hatched, they are ready for life at sea and leave the nest with their mother. Eiders and their young gather in flocks along the coasts where they feed on isopods (Idotea), crustaceans, small crabs and fish. The eider is an excellent swimmer and can dive to a depth of between 3 and 20 meters. The adult eider may seem rather ungainly in flight, flying low above sea level, sometimes touching the water with its feet in order to pick up speed. However, I know from personal experience that the eider can fly with an impressive speed. Years ago I was driving along the coast of Skálafjørður, where an eider took off from the water and flew a few kilometers parallel to the car. All the way it kept pace with vehicle at a speed of 80 km per hour, using only a few meters to land next to another eider.

In summer, the males lose their splendid plumage for a short period and start looking more like the females. But at the end of the summer, they regain their colourful plumage. You will then be able to distinguish between the sexes as the chest of the young males gradually becomes white.

As stated above, the Faroese eider is a sedentary bird found in the Faroes all year round. It has no need of migrating to warmer countries since the warm Gulf Stream keeps the waters along the coasts at a fairly constant temperature. You will therefore be able to see this beautiful bird in all seasons. Even in stormy weather flocks of eiders can be seen swaying in turbulent seas, almost as a symbol of the calm, almost phlegmatic temperament needed to survive out here in the powerful grips of the Atlantic Ocean.