2008

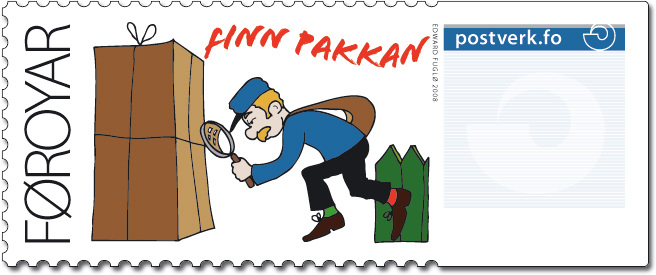

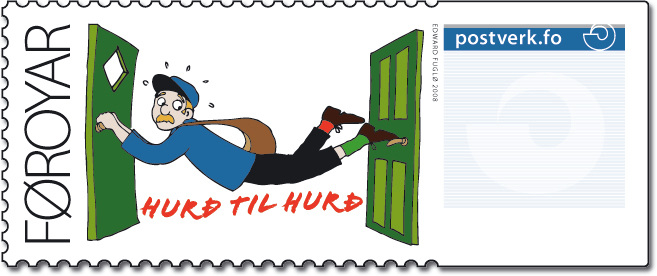

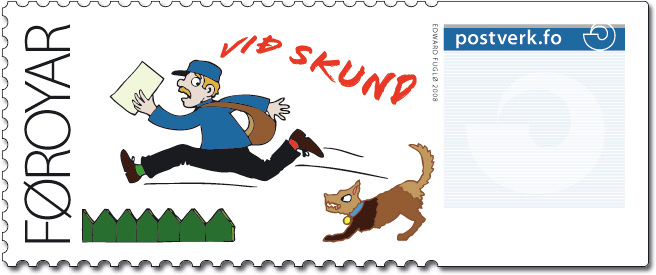

Franking Labels 2008

Date Of Issue 09.10.2008

Date Of Issue 09.10.2008

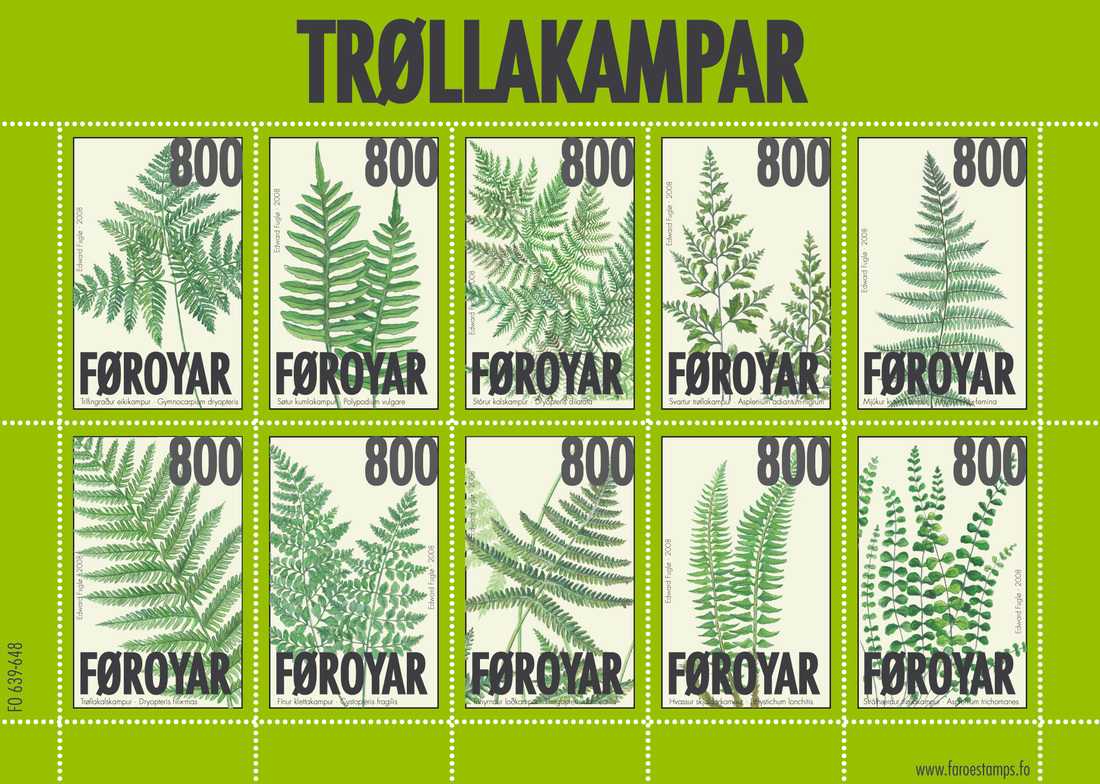

Ferns

Date Of Issue 22.09.2008

Date Of Issue 22.09.2008

Ferns are flowerless plants

Ferns belong to the group of plants that are known as flowerless. There are about 20,000 different kinds of fern and this group is the biggest after the group of flowering plants, which numbers 250,000 different kinds. Most ferns are found in the tropics and thrive best in damp surroundings.

Ferns are considered primitive plants that are closely related to primeval plants. They have neither flowers nor seeds and reproduce with the help of spores which, in some kinds, accumulate in spore clusters on the underside of fronds and are protected by a shield that opens when the spores have matured so that they can spread. In other kinds, the spores are attached to the edges of the fronds that are curled inwards as long as the spores have not matured.

Some kinds have two kinds of frond: a sterile frond and a fertile frond. The fertile fronds of some ferns may have a completely different appearance than the sterile fronds. A fern can produce millions of spores, but few of them become new plants.

Spores have different shapes. They can be kidney-shaped or round, of different colours – light or dark – and these differences are often used to identify them.

Fronds also differ. They may be subdivided into one, two, or more leaflets, or not subdivided at all. An important characteristic of ferns is that they resemble a fiddlehead before they are fully grown due to their special growth conditions.

The Faroese name for fern is 'trøllakampar', which means 'troll's beard' and not 'troll's comb' as is often heard.

Ferns were very common in the Faroes before the 'landnam' period. This can be seen from seed corn surveys. All plant growth in the Faroes depends on sheep grazing and this is the way it has been since people first came to the islands. The sheep they brought with them immediately began to gorge themselves on the lush vegetation that was found on the islands at that time. This vegetation rapidly disappeared and was replaced by the 'close-cropped' appearance we are familiar with today.

But the sheep could not eat everything, so it is possible to see the remains of the original vegetation in ravines and on ledges that they could not reach. Here, the vegetation is luxuriant and varied and surveys have shown that the plants have lived in these locations for a long time – precisely because they were out of the reach of sheep and people.

Many kinds of fern can be found in steep terrain. Most prominent are the big male ferns (dryopteris filix-mas) and the almost equally big female fern (athyrium filix-femina). Seed corn surveys have shown that the occurrence of ferns was reduced dramatically after people settled in the Faeroes with their domestic animals.

There are fifteen kinds of fern in the Faroes. Most of them grow in clefts in rocks where there is moisture and shade, but they can also be found in stony and steep terrain and ravines. The most common Faroese fern is the 'fragile fern' (cystopteris fragilis). 'Black spleenwort' (asplenium adiantum-nigrum) and 'maidenhair spleenwort' (asplenium trichomanes), on the other hand, are very rare and can be found in only one place. A new fern was discovered in 2007 at Norðuroyggjar. This was a 'hart's tongue fern' (asplenium scolopendrium), which is also rare in the Nordic countries.

Anna Maria Fosaa

Ferns belong to the group of plants that are known as flowerless. There are about 20,000 different kinds of fern and this group is the biggest after the group of flowering plants, which numbers 250,000 different kinds. Most ferns are found in the tropics and thrive best in damp surroundings.

Ferns are considered primitive plants that are closely related to primeval plants. They have neither flowers nor seeds and reproduce with the help of spores which, in some kinds, accumulate in spore clusters on the underside of fronds and are protected by a shield that opens when the spores have matured so that they can spread. In other kinds, the spores are attached to the edges of the fronds that are curled inwards as long as the spores have not matured.

Some kinds have two kinds of frond: a sterile frond and a fertile frond. The fertile fronds of some ferns may have a completely different appearance than the sterile fronds. A fern can produce millions of spores, but few of them become new plants.

Spores have different shapes. They can be kidney-shaped or round, of different colours – light or dark – and these differences are often used to identify them.

Fronds also differ. They may be subdivided into one, two, or more leaflets, or not subdivided at all. An important characteristic of ferns is that they resemble a fiddlehead before they are fully grown due to their special growth conditions.

The Faroese name for fern is 'trøllakampar', which means 'troll's beard' and not 'troll's comb' as is often heard.

Ferns were very common in the Faroes before the 'landnam' period. This can be seen from seed corn surveys. All plant growth in the Faroes depends on sheep grazing and this is the way it has been since people first came to the islands. The sheep they brought with them immediately began to gorge themselves on the lush vegetation that was found on the islands at that time. This vegetation rapidly disappeared and was replaced by the 'close-cropped' appearance we are familiar with today.

But the sheep could not eat everything, so it is possible to see the remains of the original vegetation in ravines and on ledges that they could not reach. Here, the vegetation is luxuriant and varied and surveys have shown that the plants have lived in these locations for a long time – precisely because they were out of the reach of sheep and people.

Many kinds of fern can be found in steep terrain. Most prominent are the big male ferns (dryopteris filix-mas) and the almost equally big female fern (athyrium filix-femina). Seed corn surveys have shown that the occurrence of ferns was reduced dramatically after people settled in the Faeroes with their domestic animals.

There are fifteen kinds of fern in the Faroes. Most of them grow in clefts in rocks where there is moisture and shade, but they can also be found in stony and steep terrain and ravines. The most common Faroese fern is the 'fragile fern' (cystopteris fragilis). 'Black spleenwort' (asplenium adiantum-nigrum) and 'maidenhair spleenwort' (asplenium trichomanes), on the other hand, are very rare and can be found in only one place. A new fern was discovered in 2007 at Norðuroyggjar. This was a 'hart's tongue fern' (asplenium scolopendrium), which is also rare in the Nordic countries.

Anna Maria Fosaa

The marsh marigold

Date Of Issue 19.05.2008

Date Of Issue 19.05.2008

The marsh marigold, the national flower of the Faroes

The marsh marigold is the most prominent flower in the lowlands and the harbinger of spring.

In the words of the song ”Sóljugentan” about a little girl who has picked a bouquet of these flowers, the marsh marigold, ”sóljan”, is the first greeting from the spring. It grows in large groups and is therefore very striking in the landscape. There can be few people who would not be delighted at the sight of them. Tales of the marsh marigold can be found in many places in literature – both in poems and songs. It has also played an important part in children’s games. Whistles can be made from the stalks as related in the song of the little brother who must not cry, but blow on the whistle instead, a whistle made from the stalk of a marsh marigold.

The scientific Faeroese name is ”Mýrisólja”, Caltha palustris L. in Latin. The first part of the name indicates that the plant grows in damp areas, while the second means ”sun eye”. In Faroese, it is therefore usually called ”sólja” or ”sóleyga”. It is a perennial that belongs to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae) and can be distinguished from the creeping buttercup and the lesser spearwort by its greater robustness, its characteristic, kidney-shaped leaves and big yellow flowers.

The marsh marigold was common on all of the islands about 10,000 years ago during the preboreal period, but almost disappeared because it was destroyed permanently in the Faroes during the 7th to 9th centuries. The entire plant is poisonous and is therefore left in peace by horses, who become sick if they eat it. But the large leaves of the marsh marigold are especially popular with sheep and cows so it disappears in the places where these animals can get to it. After the colonisation, this was particularly the case where it was not protected against grazing.

The Faroes’ mild, oceanic climate with its warm winters means that sheep can be out of doors all year round, but they are kept out of the home fields from 15 May to 20 October so that the grass can grow unmolested and later be used as hay or silage. If the sheep were allowed into the home fields throughout the year, the marsh marigold would probably die out according to ”Studies in the vegetational history of the Faroe and Shetland Islands” by Jóhannes Johansen.

The plant is common in the lowlands, but can also be found in the mountains in places inaccessible to sheep. The marsh marigold grows predominantly along the streams in the lowlands, but also grows in waterlogged fields. It flowers from May to the beginning of June and is widespread in many places around the world in the temperate and Arctic vegetation belt, both north and south of the Faroes.

The marsh marigold was nominated as the national flower of the Faroes in 2005 in a vote on the Internet that everybody could take part in. There was an option of eight different plants and the marsh marigold won, thereby becoming our national flower.

Anna Maria Fosaa

The marsh marigold is the most prominent flower in the lowlands and the harbinger of spring.

In the words of the song ”Sóljugentan” about a little girl who has picked a bouquet of these flowers, the marsh marigold, ”sóljan”, is the first greeting from the spring. It grows in large groups and is therefore very striking in the landscape. There can be few people who would not be delighted at the sight of them. Tales of the marsh marigold can be found in many places in literature – both in poems and songs. It has also played an important part in children’s games. Whistles can be made from the stalks as related in the song of the little brother who must not cry, but blow on the whistle instead, a whistle made from the stalk of a marsh marigold.

The scientific Faeroese name is ”Mýrisólja”, Caltha palustris L. in Latin. The first part of the name indicates that the plant grows in damp areas, while the second means ”sun eye”. In Faroese, it is therefore usually called ”sólja” or ”sóleyga”. It is a perennial that belongs to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae) and can be distinguished from the creeping buttercup and the lesser spearwort by its greater robustness, its characteristic, kidney-shaped leaves and big yellow flowers.

The marsh marigold was common on all of the islands about 10,000 years ago during the preboreal period, but almost disappeared because it was destroyed permanently in the Faroes during the 7th to 9th centuries. The entire plant is poisonous and is therefore left in peace by horses, who become sick if they eat it. But the large leaves of the marsh marigold are especially popular with sheep and cows so it disappears in the places where these animals can get to it. After the colonisation, this was particularly the case where it was not protected against grazing.

The Faroes’ mild, oceanic climate with its warm winters means that sheep can be out of doors all year round, but they are kept out of the home fields from 15 May to 20 October so that the grass can grow unmolested and later be used as hay or silage. If the sheep were allowed into the home fields throughout the year, the marsh marigold would probably die out according to ”Studies in the vegetational history of the Faroe and Shetland Islands” by Jóhannes Johansen.

The plant is common in the lowlands, but can also be found in the mountains in places inaccessible to sheep. The marsh marigold grows predominantly along the streams in the lowlands, but also grows in waterlogged fields. It flowers from May to the beginning of June and is widespread in many places around the world in the temperate and Arctic vegetation belt, both north and south of the Faroes.

The marsh marigold was nominated as the national flower of the Faroes in 2005 in a vote on the Internet that everybody could take part in. There was an option of eight different plants and the marsh marigold won, thereby becoming our national flower.

Anna Maria Fosaa

Europa 2008 – Letter

Date Of Issue 19.05.2008

Date Of Issue 19.05.2008

Letters and haste

Why do older people find it so hard to accept new things and methods that emerge? Why are they unsure instead of applauding every advance and welcoming innovations with open arms? Maybe it’s because they don’t miss these useful items because they have never had them and find them completely superfluous. Or maybe they are scared of the new but unable to put why they think it’s dangerous into words. They are perhaps thinking of the old proverb with its admonitory undertones: “You can’t have your cake and eat it”. It’s not really surprising, as in recent years things have come and gone at such a rate that many people simply can’t keep up with all the things you simply have to have if you want to be able to live your life at all.

Somewhere, at the back of our minds, we have the occasional inkling of a hollow cry for help, which is stifled immediately, because we all have to keep up with the times, don’t we, or we will end up as grumpy old relics. So many older people are obediently learning to key text messages into their mobiles.

No one asks who is controlling all the waves that come crashing over us. Nor does anyone seem to be in any doubt about whether this is the only right thing for heart and soul. Maybe we should in fact ask ourselves from time to time what it is doing to us and our lives. Everything has to go faster and faster. Traffic and all communication between people. But why all the haste? What are we running after? Where are we heading?

Email is really clever – you can send messages all over the globe. It only takes a couple of seconds for the email to reach the person it was sent to. But what do these emails contain? Mostly just short messages and inquiries.

What about the other letters? The ones that reflect another century, a time that is past. Has that sort of letter disappeared for good together with a time that we whipped to a froth because we never had enough of it? Isn’t time something you take. For example, you take a moment when a letter arrives in the post. You gaze at the envelope, look at the address and the stamp. You open the envelope and take out the letter itself. A voice speaks to you, tells you various things and maybe philosophises a bit before bidding you a cordial farewell. You can put the letter back in the envelope, keep it and take it out again several years later to relive the words and remember the time when it was written. Just like hearing an old tune that brings back memories.

Life shouldn’t just be made up of memories and we shouldn’t spend all our time thinking about the past, but isn’t it important too to be left with something once the years have rolled by? Or should everything simply be controlled by technology and deleted with a keystroke once the message has been sent?

It isn’t really possible to stop development, but wouldn’t it be better if we were in control of these conveniences instead of them controlling us. Don’t let the living letter disappear, the letter that someone has penned by hand, then written your name on the envelope, written where you live and stuck a stamp in the top right-hand corner. It’s a much too important – and basically very reassuring – part of our everyday life to let it just disappear into the clamour of our age.

It would be a great shame.

Marianna Debes Dahl

Why do older people find it so hard to accept new things and methods that emerge? Why are they unsure instead of applauding every advance and welcoming innovations with open arms? Maybe it’s because they don’t miss these useful items because they have never had them and find them completely superfluous. Or maybe they are scared of the new but unable to put why they think it’s dangerous into words. They are perhaps thinking of the old proverb with its admonitory undertones: “You can’t have your cake and eat it”. It’s not really surprising, as in recent years things have come and gone at such a rate that many people simply can’t keep up with all the things you simply have to have if you want to be able to live your life at all.

Somewhere, at the back of our minds, we have the occasional inkling of a hollow cry for help, which is stifled immediately, because we all have to keep up with the times, don’t we, or we will end up as grumpy old relics. So many older people are obediently learning to key text messages into their mobiles.

No one asks who is controlling all the waves that come crashing over us. Nor does anyone seem to be in any doubt about whether this is the only right thing for heart and soul. Maybe we should in fact ask ourselves from time to time what it is doing to us and our lives. Everything has to go faster and faster. Traffic and all communication between people. But why all the haste? What are we running after? Where are we heading?

Email is really clever – you can send messages all over the globe. It only takes a couple of seconds for the email to reach the person it was sent to. But what do these emails contain? Mostly just short messages and inquiries.

What about the other letters? The ones that reflect another century, a time that is past. Has that sort of letter disappeared for good together with a time that we whipped to a froth because we never had enough of it? Isn’t time something you take. For example, you take a moment when a letter arrives in the post. You gaze at the envelope, look at the address and the stamp. You open the envelope and take out the letter itself. A voice speaks to you, tells you various things and maybe philosophises a bit before bidding you a cordial farewell. You can put the letter back in the envelope, keep it and take it out again several years later to relive the words and remember the time when it was written. Just like hearing an old tune that brings back memories.

Life shouldn’t just be made up of memories and we shouldn’t spend all our time thinking about the past, but isn’t it important too to be left with something once the years have rolled by? Or should everything simply be controlled by technology and deleted with a keystroke once the message has been sent?

It isn’t really possible to stop development, but wouldn’t it be better if we were in control of these conveniences instead of them controlling us. Don’t let the living letter disappear, the letter that someone has penned by hand, then written your name on the envelope, written where you live and stuck a stamp in the top right-hand corner. It’s a much too important – and basically very reassuring – part of our everyday life to let it just disappear into the clamour of our age.

It would be a great shame.

Marianna Debes Dahl

Klaksvík 100 Years

Date Of Issue 11.02.2008

Date Of Issue 11.02.2008

As the earliest records from 1584 show, there are five villages/districts in Klaksvík: í Gerðum, á Myrkjanoyri, á Uppsølum, í Vági and á Norðoyri. The location was called Bø by people from the Northern Isles and by those from the east side of Eysturoy, while people from other places used the name í Vági or Norðuri í Vági.

The first settlement at Klaksvík dates back to Viking times, but it was not before the 20th century that the districts merged to form a large, modern, Faroese town that became the cultural and commercial centre for the Northern Isles and the Faroes as a whole. Klaksvík, which was amalgamated in a joint municipality with the rest of the Northern Isles in 1873, became an independent municipality in 1908. At the time, about 700 people lived in the parish, but 50 years later, the population of Klaksvík had risen to more than 4,000. During the first half of the 20th century Klaksvík was that town in the Faroes that enjoyed the greatest commercial success.

The town grew from five small districts in the Northern Isles in the middle of the 19th century to the best fishing port in the country around 1960. It was quite natural for Klaksvík, which is located next to one of the best harbours in the Faroes, to become the commercial centre of the region. Today, 5,000 people live in the biggest fishing community in the Faroes and several municipalities in the Northern Isles have chosen to merge with Klaksvík Municipality.

It could quite well be the case that the Northern Isles will soon be a single municipality once again. If this proves to be the case, the municipality will have a population of 6,000. New challenges and opportunities lie ahead for Klaksvík Municipality. In 2006, the Northern Isles became connected with the central Faroes via the undersea Norðoya tunnel to Leirvík on Eysturoy.

This presented Klaksvík with a challenge as the natural centre of the northern part of the Faroes. But is also provided Klaksvík with an opportunity to become the centre of a powerful northern region that can compete with the central Faroes in the globalised community where there are no longer geographical limitations.

Hans Andrias Sølvará

The first settlement at Klaksvík dates back to Viking times, but it was not before the 20th century that the districts merged to form a large, modern, Faroese town that became the cultural and commercial centre for the Northern Isles and the Faroes as a whole. Klaksvík, which was amalgamated in a joint municipality with the rest of the Northern Isles in 1873, became an independent municipality in 1908. At the time, about 700 people lived in the parish, but 50 years later, the population of Klaksvík had risen to more than 4,000. During the first half of the 20th century Klaksvík was that town in the Faroes that enjoyed the greatest commercial success.

The town grew from five small districts in the Northern Isles in the middle of the 19th century to the best fishing port in the country around 1960. It was quite natural for Klaksvík, which is located next to one of the best harbours in the Faroes, to become the commercial centre of the region. Today, 5,000 people live in the biggest fishing community in the Faroes and several municipalities in the Northern Isles have chosen to merge with Klaksvík Municipality.

It could quite well be the case that the Northern Isles will soon be a single municipality once again. If this proves to be the case, the municipality will have a population of 6,000. New challenges and opportunities lie ahead for Klaksvík Municipality. In 2006, the Northern Isles became connected with the central Faroes via the undersea Norðoya tunnel to Leirvík on Eysturoy.

This presented Klaksvík with a challenge as the natural centre of the northern part of the Faroes. But is also provided Klaksvík with an opportunity to become the centre of a powerful northern region that can compete with the central Faroes in the globalised community where there are no longer geographical limitations.

Hans Andrias Sølvará

All Issues Copyright Posta, www.stamps.fo