2007

Life in a stone fence

Date Of Issue 01.10.2007

Date Of Issue 01.10.2007

Stone wall enclosed inlying fields All Faroese villages are surrounded by dry stone walls, which are often many hundreds of years old. The walls separate the inlying fields from the outlying fields, which is an important feature of Faroese agriculture. The winters are so mild here that sheep are kept outdoors all year round. However, from 15 May to 20 October the gates to inlying fields are closed to sheep, so that the grass remains undisturbed, can grow and in the autumn can be harvested for hay or silage. After the last of the hay and all potatoes have been cleared from the inlying fields, the gates are opened once again and sheep can enjoy the last of the summer grass. The grass also grows in the mild winter, particularly in low inlying fields which are also fertilized each year. You can in some villages see how the dry stone walls have been gradually developed over time, as more and more land has been included into the inlying fields. The first walls were ‘cow high’, to prevent cows that are herded into the outlying fields in the summer months, getting in. The walls were then made ‘sheep high’, so that sheep could not jump over them and get to the luxuriant inlying field grass in the summer. In a village such as Velbastaður, directly west of Tórshavn, you can still clearly see the inlying field development. The dry stone walls of the inlying fields are a typical biological marginal zone. This means that they form a transition zone between two completely different environments - the outlying fields and the inlying fields. The marginal zones contain a unique plant and animal life, which also means that there can be a wider diversity and different species of plants and animals in the marginal zone than on each side of the wall. Species diversity is therefore greater in the marginal zone than in the zones on each side. A further marginal zone is found when moving up into the mountains, at the height where the vegetation changes from being low land temperate to arctic mountain vegetation. We find greater species diversity in this zone than both at lower and higher altitudes. Other Faroese marginal zones are bird cliffs and the shore zone. The animal and plant life of dry stone walls A wide diversity of plant species are found along dry stone walls and on the ledges between wall stones, some of the most common being the red flowering grass red fescue (Festuca rubra) and the yellow flower species hawkweed (Hieracium spp.), autumn hawkbit (Leontodon autumnalis) and also early in the summer, the common dandelion (Taraxacum vulgaris). Dry stone walls are ideal haunts for small birds, which use the walls as a place to sit when singing to attract a mate and later when the female broods, from where the male sings to keep other males at bay and to assert his territory. Small birds also build their nests between the stones to prevent cats getting to eggs and chicks. Here you can find the winter wren (Troglodytes troglodytes), the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris), the northern wheateater (Oenanthe oenanthe) and the meadow pipit and the rock pipit (Anthus pratensis and A. petrosus). On the islands, where there are no rats, dry stone walls are the classic breeding ground for the little European storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus). On cold mornings you can even see common snipe (Gallinago gallinago) and common redshank (Tringa totanus) sitting on the walls. In the shadows between wall stones you can find several types of larger and smaller ferns, the most common being deer fern (Blechnum spicant) and fragile fern (Cystopteris fragilis). Old walls are usually overgrown with moss and lichen, including the light coloured species of crabseye lichen (Ochrolechia spp.) and species of the light grey foliose lichens (Parmelia spp.). If the affects of bird fertilization are strong, the walls can be turned completely yellow with the common maritime sunburst lichen (Xanthoria parietina) and brown with the foliose brown fringe lichen Anaptychia runcinata. There are large numbers of insects among the moss and lichen, which birds also eat. You can see crane fly, earwigs, millipede and centipede and several types of beetle including the very common ground beetle, Nebria rufescens, which is unique by either having red or black legs. In the damp moss you can also find slugs, both the small brown-grey slug, the larger black European black slug (Arion ater) and unfortunately also in recent years the Spanish slug (Arion lucitanicus), which has become far too common. If the around the dry stone walls is damp, you can also find the red marsh willowherb (Epilobium palustre), which is however also common in wet surroundings along streams. On warm sunny days the air above the walls teams with large number of midges, which again are food for small birds.

Dorete Bloch and Anna Maria Fosaa

Dorete Bloch and Anna Maria Fosaa

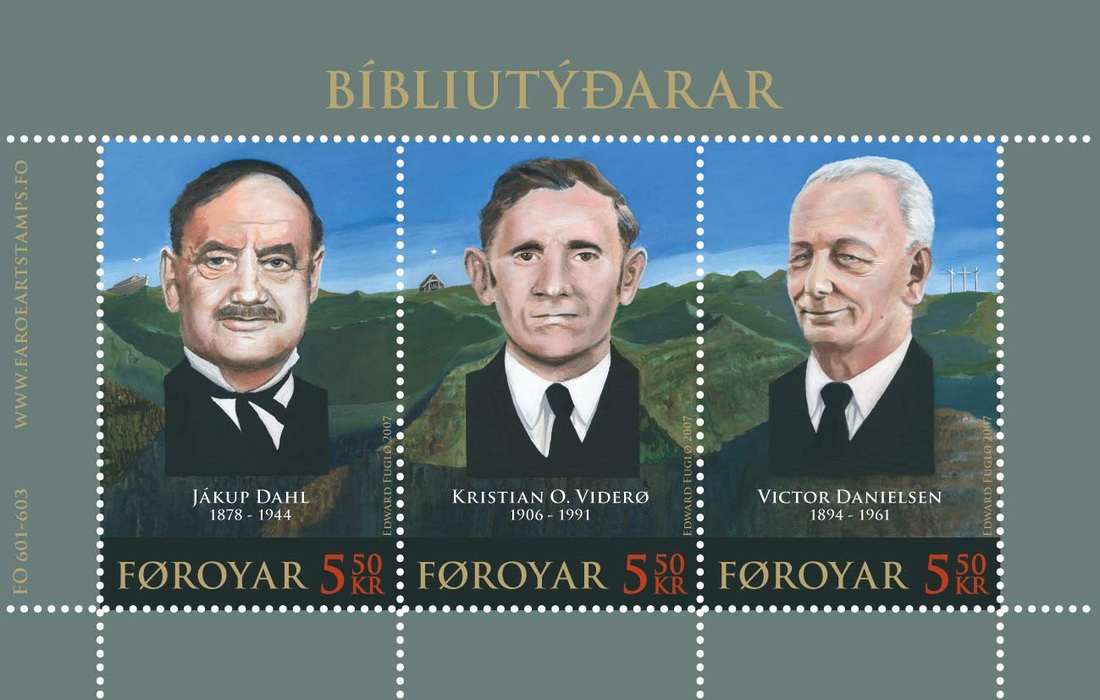

Bible Translators

Date Of Issue 11.06.2007

Date Of Issue 11.06.2007

Jákup Dahl

Jákup Dahl was born in 1878 in the village Vágur on Suðuroy. He was the son of a local merchant. In 1893 the 15 years old Dahl went to Tórshavn to the College of Education. In 1897 Dahl went to Denmark, where he first took a high school education and then, in 1899 started his theological studies at the University of Copenhagen, where he graduated in 1905. In 1907-08, Dahl worked as a teacher at Karise folk high school in Denmark, whereupon he went back to the Faroe Islands and became a teacher at the junior high school and the College of Education. In those days, it was forbidden to teach in the native language, but Dahl ignored this ban and teached his Faroese students in Faroese, until he left the position in 1912. Later the same year, Jákup Dahl became vicar in Tórshavn parish. Six years later, in 1918, he was appointed as rural dean for the Faroe Islands, and held this position until his death in 1944. Even from his younger days, Jákup Dahl was engaged by the new nationalistic currents. Like many other vicars - among others, his friend from the student days and predecessor as rural dean, A. C. Evensen (1874-1917) - Dahl wanted the liturgical language translated into Faroese. In 1918-19 he had translated the “rituals”, but because of political disputes over them, they were not printed until 1929 and authorized in 1930. He started to translate the New Testament from Greek, and the different chapters were published in booklets in the period from 1923 to 1936. In 1937 he published a final version of the New Testament. Back in 1921 Dahl had translated The Psalms from the Old Testament. By other works for ecclesiastical- and educational purposes, Dahl translated Luther’s Catechism (1922), Balslev’s book of Bible’s stories (1924) and some devotional books and books of sermons for the parish clerks.

In addition to his other ecclesiastical works, Dahl also wrote a series of hymns, and translated about 70–80 hymns from other languages, all part of the Faroese hymn book. As early as in 1908, Dahl wrote a grammar for schoolchildren, which has been used in Faroese schools until recently.

Apart from his ecclesiastical and linguistic works, Jákup Dahl also left a great amount of secular prose and poetry behind.

K. O. Viderø

Kristian Osvald Viderø was born in the village Skálavík on Sandoy in 1906.

Like most of his contemporaries, K. O. Viderø started as a fisherman at a very young age. But in the twenties, he went to Copenhagen, where he, despite great misery, got a high school degree in 1930 and a degree in divinity in 1941. The relative long period of study was caused by Viderø’s restless nature and was interrupted by long journeys, which brought him all over Europe. He visited the Sami in Northern Norway, went as far east as to the Volga River, to Balkan, Middle East and even Northern Africa. His wanderlust made the eloquent Viderø a popular storyteller among his fellow students in Copenhagen, where the colourful stories from his travels made the listeners gape by surprise or scream of laughter. In the period from 1947 to 1977, K. O. Viderø was vicar at several churches on the Faroe Islands. His last parish was the northern parish of Suðuroy, where he worked from 1969 until his retirement in 1977.

There are a vast number of anecdotes about Viderø as a vicar, about his absent minded personality and fabulating sermons, which mostly were performed without a manuscript. After J. Dahl’s death, the task of finishing the translation of the Bible fell on Viderø, who translated from Hebrew. This great work resulted in the authorized version of the Bible, published by the established church in 1961.

After his retirement in 1977, Viderø started to travel again in Southern Europe, the Middle East and Asia, and never returned to the Faroe Islands. He died in Copenhagen in 1991.

Victor Danielsen

Victor Danielsen was born in the village Søldarfjørður on Eysturoy in 1894. In 1911, Danielsen went to the College of Education in Tórshavn and graduated in 1914. That same year, he became a teacher at the small village schools in Søldarfjørður, Glyvrar and Lambi, but quit his job after only six or seven months to become a missionary. In 1916, Danielsen left the established church and became a member of the Free Church called Brøðrasamkoman (A Faroese counterpart to the “Plymouth Brethrens”, established on the Faroes by the Scottish missionary William Sloan).

In 1920 Victor Danielsen married his wife Henrikka Malena, and in 1928 they moved to Fuglafjørður, where he worked as a preacher and missionary for “Brøðrasamkoman”. In 1930, the participants of a conference at “Brøðrasamkoman” in Tórshavn agreed to ask Danielsen to translate the Epistle of the Galatians into Faroese. The congregation became so enthusiastic by the result, that they asked Danielsen to translate the rest of the New Testament. This translation was published in March 1937, a few weeks before J. Dahl’s Authorized Version.

After the work of translating the New Testament, he started to translate the rest of the Bible, and already in 1939 he had finished his task, based on translations to other Nordic languages. But because of the outbreak of World War II, Danielsen’s translation was not published before 1949 – and this involuntary delay gave Danielsen an opportunity to revise the linguistic form of his translation.

Victor Danielsen was an extraordinary energetic and productive man. Apart from his translations of the New Testament and the Bible, he wrote 27 hymns and translated more than 800 hymns and songs. He also wrote two novels with spiritual content.

Victor Danielsen died in 1961.

Three outstanding and quite different personalities. But all three of them pushed onwards by energy, national feelings and a common desire to give the Faroese the opportunity to read the Bible in their own language.

More comprehensive descriptions of the three Bible translators and the circumstances which caused their enormous tasks are available at www.faroeartstamps.fo.

Jákup Dahl was born in 1878 in the village Vágur on Suðuroy. He was the son of a local merchant. In 1893 the 15 years old Dahl went to Tórshavn to the College of Education. In 1897 Dahl went to Denmark, where he first took a high school education and then, in 1899 started his theological studies at the University of Copenhagen, where he graduated in 1905. In 1907-08, Dahl worked as a teacher at Karise folk high school in Denmark, whereupon he went back to the Faroe Islands and became a teacher at the junior high school and the College of Education. In those days, it was forbidden to teach in the native language, but Dahl ignored this ban and teached his Faroese students in Faroese, until he left the position in 1912. Later the same year, Jákup Dahl became vicar in Tórshavn parish. Six years later, in 1918, he was appointed as rural dean for the Faroe Islands, and held this position until his death in 1944. Even from his younger days, Jákup Dahl was engaged by the new nationalistic currents. Like many other vicars - among others, his friend from the student days and predecessor as rural dean, A. C. Evensen (1874-1917) - Dahl wanted the liturgical language translated into Faroese. In 1918-19 he had translated the “rituals”, but because of political disputes over them, they were not printed until 1929 and authorized in 1930. He started to translate the New Testament from Greek, and the different chapters were published in booklets in the period from 1923 to 1936. In 1937 he published a final version of the New Testament. Back in 1921 Dahl had translated The Psalms from the Old Testament. By other works for ecclesiastical- and educational purposes, Dahl translated Luther’s Catechism (1922), Balslev’s book of Bible’s stories (1924) and some devotional books and books of sermons for the parish clerks.

In addition to his other ecclesiastical works, Dahl also wrote a series of hymns, and translated about 70–80 hymns from other languages, all part of the Faroese hymn book. As early as in 1908, Dahl wrote a grammar for schoolchildren, which has been used in Faroese schools until recently.

Apart from his ecclesiastical and linguistic works, Jákup Dahl also left a great amount of secular prose and poetry behind.

K. O. Viderø

Kristian Osvald Viderø was born in the village Skálavík on Sandoy in 1906.

Like most of his contemporaries, K. O. Viderø started as a fisherman at a very young age. But in the twenties, he went to Copenhagen, where he, despite great misery, got a high school degree in 1930 and a degree in divinity in 1941. The relative long period of study was caused by Viderø’s restless nature and was interrupted by long journeys, which brought him all over Europe. He visited the Sami in Northern Norway, went as far east as to the Volga River, to Balkan, Middle East and even Northern Africa. His wanderlust made the eloquent Viderø a popular storyteller among his fellow students in Copenhagen, where the colourful stories from his travels made the listeners gape by surprise or scream of laughter. In the period from 1947 to 1977, K. O. Viderø was vicar at several churches on the Faroe Islands. His last parish was the northern parish of Suðuroy, where he worked from 1969 until his retirement in 1977.

There are a vast number of anecdotes about Viderø as a vicar, about his absent minded personality and fabulating sermons, which mostly were performed without a manuscript. After J. Dahl’s death, the task of finishing the translation of the Bible fell on Viderø, who translated from Hebrew. This great work resulted in the authorized version of the Bible, published by the established church in 1961.

After his retirement in 1977, Viderø started to travel again in Southern Europe, the Middle East and Asia, and never returned to the Faroe Islands. He died in Copenhagen in 1991.

Victor Danielsen

Victor Danielsen was born in the village Søldarfjørður on Eysturoy in 1894. In 1911, Danielsen went to the College of Education in Tórshavn and graduated in 1914. That same year, he became a teacher at the small village schools in Søldarfjørður, Glyvrar and Lambi, but quit his job after only six or seven months to become a missionary. In 1916, Danielsen left the established church and became a member of the Free Church called Brøðrasamkoman (A Faroese counterpart to the “Plymouth Brethrens”, established on the Faroes by the Scottish missionary William Sloan).

In 1920 Victor Danielsen married his wife Henrikka Malena, and in 1928 they moved to Fuglafjørður, where he worked as a preacher and missionary for “Brøðrasamkoman”. In 1930, the participants of a conference at “Brøðrasamkoman” in Tórshavn agreed to ask Danielsen to translate the Epistle of the Galatians into Faroese. The congregation became so enthusiastic by the result, that they asked Danielsen to translate the rest of the New Testament. This translation was published in March 1937, a few weeks before J. Dahl’s Authorized Version.

After the work of translating the New Testament, he started to translate the rest of the Bible, and already in 1939 he had finished his task, based on translations to other Nordic languages. But because of the outbreak of World War II, Danielsen’s translation was not published before 1949 – and this involuntary delay gave Danielsen an opportunity to revise the linguistic form of his translation.

Victor Danielsen was an extraordinary energetic and productive man. Apart from his translations of the New Testament and the Bible, he wrote 27 hymns and translated more than 800 hymns and songs. He also wrote two novels with spiritual content.

Victor Danielsen died in 1961.

Three outstanding and quite different personalities. But all three of them pushed onwards by energy, national feelings and a common desire to give the Faroese the opportunity to read the Bible in their own language.

More comprehensive descriptions of the three Bible translators and the circumstances which caused their enormous tasks are available at www.faroeartstamps.fo.

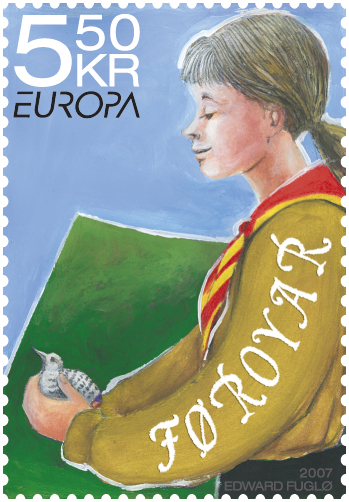

Europa 2007 – 100 Years Of The Scout Movement

Date Of Issue 10.04.2007

Date Of Issue 10.04.2007

European postal operators, organised under PostEurop, conclude an annual agreement on the publication of common European stamps with a specific theme. This year’s European stamps are based on the theme of “100 years of the Scout Movement”. What does it mean to be a scout? “Scouting is a game with a purpose,” said Baden-Powell, the founder of the scout movement. On 29 July 1907, he organised the first ever scout camp on Brownsea Island in the UK. In 1908, he published a book entitled “Scouting for Boys”. The scout movement spread fast throughout the world and soon became the largest child and youth movement in the world. Today, 100 years after its foundation, the scout movement is in rude health, with over 28 million scouts in more than 216 countries. The fundamental concept of the scout movement has remained unchanged over the years, despite various ups and downs and changes. The aim of the Scout movement is to contribute to the development of young people so that they can realise their full physical, intellectual, social and spiritual potential as individuals, as responsible citizens and as members of their local, national and international communities. One of the fundamental principles is that children develop when they are shown trust and when they have challenges in which they can test their scouting skills. The rules according to which scouts around the world work are enshrined in the scout law and scout promise. Three international principles form the basis of the work of the scout movement: • The individual: scouts are responsible for their own development • The environment: scouts show respect for their fellow human beings, are helpful and act responsibly in relation to nature and the society we are part of • The spiritual: scouts aim to find a belief, a spiritual principle, that is greater than human beings Scouts around the world have many other common characteristics, for example the scout uniform, the training system, the scout greeting, the scout law, the scout promise and the scout motto, “be prepared”. Scouts Scout life is fun, inventive, motivational and adapted to the age group, so that everyone can participate. Scouts learn to be out in the countryside together with others and to cope in society on their own. They are also able to test themselves in competitions, exercises and camps. Children must be 10 years old to become scouts. On Saint George’s Day on 23 April, all scouts around the world make their scout promise. A special ceremony is held for those who are making the scout promise for the first time and thus becoming members of one of the scout patrols. The scout patrol is one of the cornerstones of scout work and has been since the foundation of the scout movement 100 years ago. In a patrol, the scouts work together under the leadership of a patrol leader, who is a person with experience and abilities. The patrol leader and the older scouts must help and train the younger scouts. A patrol of scouts of different ages works best because the younger ones have something to live up to. There are always competitions of various kinds. Scouts also go for walks in the countryside at all times of the year. Camps Camps are also a regular part of scouting life. There are usually two troop camps a year. The entire troop is together at a troop camp and there is always something exciting on the programme. Patrol camps are organised by individual patrols. Each patrol has a tent and a patrol box with everything it needs in a camp. When there are association camps, all troops and patrols in the association attend. Sometimes there are joint camps with all the scouts in the Faroes. It is also possible to go to a camp abroad. As a rule, scouts can go to a camp abroad twice while they are scouts. Once during their time as scouts, they can also go on a World Jamboree. The Jamboree is held every four years and is for scouts throughout the world. The Scout Movement in the Faroes The scout movement came to the Faroes in 1926. Boys had previously attempted to create their own scout patrols but they failed every time. But then four boys in Torshavn decided to start a scout group. Eskild Christiansen was the pioneer and the idea was to stop the fights that then took place between the different quarters in Torshavn. The scouts met in the basement of Eskild’s grandfather’s house and they got a Dane, Henning Aage Holm (Bomme), to be troop leader. This was the beginning of Skótafylki Sigmunds Brestisonar (Sigmunds Brestisson Scout Association) and the Faroese scout movement. There are now four different associations and 30 scout groups around the country, with a total of 1500 scouts.www.scout.fo

The seal woman

Date Of Issue 12.02.2007

Date Of Issue 12.02.2007

The legend of the seal-woman is well known in all the North Atlantic coastal regions. It is a moving story of a situation that people from all maritime cultures can recognise.

It touches on the great mysteries of life: love and betrayal, evil and death, beauty and wickedness, purity and faithfulness. There is a meaning in it for everyone, so it has always been popular. Even modern people are still fascinated by the haunting tale.

Two Faroese villages are particularly associated with the legend. The most famous version comes from Mikladalur on the island of Kalsoy, because this is the one reproduced by V. U. Hammershaimb in his Faroese Anthology in 1891. The story is also known from an ancient ballad. It is the tale of a farmer’s son from Mikladalur, who steals the skin of a young seal-girl, leaving her naked, so that she cannot return to the sea. She is forced to live as his wife for many years, until one day she finds her lost sealskin locked away. She puts it on and is able to return to her seal mate, who has been waiting for her all this time by the landing place. It is said that the descendants of the farmer’s son and the seal-woman have hands that look like a seal’s flippers. A similar version of the tale is told about the villagers from Hamar in Skálavík on Sandoy.

The version from Mikladalur ends in the worst imaginable tragedy. According to this legend, the men of the village decided to go seal hunting. The night before the hunt, the seal-woman returns in a dream to her husband and begs him to spare her mate and their two new-born seal pups. She tells him where they are sheltering in a breeding cave, so that he can recognise them. But instead of sparing them, the man finds and kills her mate and the pups. Then he cooks the meat for supper and eats it with his children. The seal-woman comes back once more, this time in the form of a fearsome she-troll, and warns them of her terrible revenge. Men will fall from the cliffs as they gather birds’ eggs, or drown while fishing, or die in other ways out in the wild elements, until there are enough of them to reach all the way round Kalsoy arm in arm. That number has still not been reached to this day.

This terrible ending is not known everywhere, and not in the version from the village of Skálavík, for instance.

In the broadest sense, this is a tale of humans and nature. Mother Nature gives, and takes back what she has given. Humans depend on nature, and should never defy its power. It is not for them to rule over Nature, and if anyone tries to do so, the consequences may be as disastrous as in the legend. It can also be regarded as a religious parable, as a warning not to challenge God, the creator who holds everything in his power.

The idea of the seal as a person comes naturally to those who live close to seals and are familiar with them. It is easy to imagine a human side to such beautiful, graceful creatures. Stories of familiar animals leaving their natural surroundings and appearing in human form are passed down everywhere in oral traditions and poetry.

Sadly, the moral of the story applies as much as ever to the way humans treat nature in our own time. Not surprisingly, many people still feel this fable is highly relevant. We are most deeply concerned about the threats of global warming and the climatic changes that will follow. The most pessimistic predictions are that nature’s revenge may be far more terrible than the seal-woman’s. Societies fighting for a cleaner environment and more respectful treatment of nature could perhaps make use of this Faroese legend in their campaigns.

It touches on the great mysteries of life: love and betrayal, evil and death, beauty and wickedness, purity and faithfulness. There is a meaning in it for everyone, so it has always been popular. Even modern people are still fascinated by the haunting tale.

Two Faroese villages are particularly associated with the legend. The most famous version comes from Mikladalur on the island of Kalsoy, because this is the one reproduced by V. U. Hammershaimb in his Faroese Anthology in 1891. The story is also known from an ancient ballad. It is the tale of a farmer’s son from Mikladalur, who steals the skin of a young seal-girl, leaving her naked, so that she cannot return to the sea. She is forced to live as his wife for many years, until one day she finds her lost sealskin locked away. She puts it on and is able to return to her seal mate, who has been waiting for her all this time by the landing place. It is said that the descendants of the farmer’s son and the seal-woman have hands that look like a seal’s flippers. A similar version of the tale is told about the villagers from Hamar in Skálavík on Sandoy.

The version from Mikladalur ends in the worst imaginable tragedy. According to this legend, the men of the village decided to go seal hunting. The night before the hunt, the seal-woman returns in a dream to her husband and begs him to spare her mate and their two new-born seal pups. She tells him where they are sheltering in a breeding cave, so that he can recognise them. But instead of sparing them, the man finds and kills her mate and the pups. Then he cooks the meat for supper and eats it with his children. The seal-woman comes back once more, this time in the form of a fearsome she-troll, and warns them of her terrible revenge. Men will fall from the cliffs as they gather birds’ eggs, or drown while fishing, or die in other ways out in the wild elements, until there are enough of them to reach all the way round Kalsoy arm in arm. That number has still not been reached to this day.

This terrible ending is not known everywhere, and not in the version from the village of Skálavík, for instance.

In the broadest sense, this is a tale of humans and nature. Mother Nature gives, and takes back what she has given. Humans depend on nature, and should never defy its power. It is not for them to rule over Nature, and if anyone tries to do so, the consequences may be as disastrous as in the legend. It can also be regarded as a religious parable, as a warning not to challenge God, the creator who holds everything in his power.

The idea of the seal as a person comes naturally to those who live close to seals and are familiar with them. It is easy to imagine a human side to such beautiful, graceful creatures. Stories of familiar animals leaving their natural surroundings and appearing in human form are passed down everywhere in oral traditions and poetry.

Sadly, the moral of the story applies as much as ever to the way humans treat nature in our own time. Not surprisingly, many people still feel this fable is highly relevant. We are most deeply concerned about the threats of global warming and the climatic changes that will follow. The most pessimistic predictions are that nature’s revenge may be far more terrible than the seal-woman’s. Societies fighting for a cleaner environment and more respectful treatment of nature could perhaps make use of this Faroese legend in their campaigns.