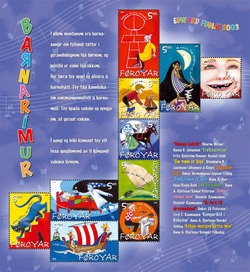

2003

Children’s songs

Date Of Issue 14.04.2003

Date Of Issue 14.04.2003

Children’s songs

“Rura, rura barnið” (lull my baby to sleep) or “Góða mamma, kom nú og set teg her hjá mær” (Oh, Mummy, come now and sit beside me) are the sort of songs many Faroese children know by heart. Their parents have hummed them over and over again to soothe them, keep them happy, lull them to sleep or just for the fun of singing.

The oldest nursery rhymes we know are probably poems or songs for children which were recited or sung to very simple tunes. In the Faroese dictionary published by Føroya Fróðskaparfelag we can see that these were “old rhymes passed on by oral tradition, which were sung repeatedly for children.” Examples of these children’s songs are: “Rógva út á krabbaskel” (Rowing out to “Krabbaskel”) and “Kú mín í garði” (My cow in the yard).

In the first publicly run schools to be established on the Faroes the children probably sang Danish songs. The well-known Faroese writer William Heinesen gives the following quite amusing description of singing lessons at the beginning of the 20th century: “Pastor Jacob Dahl also took us for singing. In these lessons we were only allowed to sing Danish songs of course, and practically the whole school would be squeezed into a single room. It was quite indescribably stuffy, and no one could ever forget the commotion. It was obviously impossible for a single teacher to keep thirty or forty imps under control when they were only interested in mischief. Pastor Dahl always tried first to be good natured, but failed nearly every time, so then he would change tactics and become strict, making threats and giving bad marks on the slightest pretext, and striking out at the nearest troublemakers with his violin bow. As a result, the bow would fray until at times it was quite unusable. Another feature of these chaotic lessons was that inevitably one or two of the violin strings broke, occasionally all four of them, to the boundless amusement of everyone attending. Every time I see a book on art history with a reproduction of Michelangelo’s painting of the Day of Judgement, I cannot help remembering these singing lessons – all the miserably crowded and cramped bodies, sitting, lying or standing on tables and benches, deafened and stifled, bawling at the tops of their voices “Vift stolt på Codans bølger” (Proudly fly over the waves of Codan), and at the same time hurling balls of paper or flicking rubbers at each other or scuffling and nursing nosebleeds, while the helpless teacher, sweating profusely, tried to reattach his broken violin strings.”

Songs specifically for children came clearly into focus when the poet Hans Andrias Djurhuus published his rhymes for children in the “Varðin” series of books in 1914 to 1919. Several different composers have set the popular poet’s words to music. The poet Regin Dahl brought out a record in the 1960s with songs written by H. A. Djurhuus. Hans Andrias’s songs, with their bright, cheerful verses and tunes were really the only songs to be sung right up to the 70s.

In fact, not many Faroese song books existed. Songbók Føroya Fólks (The Faroese people’s song book), Føroysk Songløg 1 og 2 (Faroese songs 1 and 2) by Waagstein and what was known as the Starabókin (the Starling book), were published by teachers from Klaksvík. There were no others.

In the mid-70s the first Faroese children’s record appeared, with Annika Hoydal singing songs by Hans Andrias and Gunnar Hoydal. This was the start of a new era when people took a lively interest in Faroese children’s songs. New books of songs were published, such as 100 sangir (100 songs) and Heiðaljóð (Sounds of the heath) by Andrias Andreassen and Kannubjølluvísur (Mare’s tail rhymes) and Barnabros (Children’s smiles) by Alexandur Kristiansen. No less than three CDs have appeared with songs by Alexandur Kristiansen, called Eplapetur (Potato Peter), Grísaflísapætur (Slice of Pork Peter) and Mánadagsmortan (Monday Martin). Alexandur truly masters the art of playing with words and witty proverbs.

Several collections of Christian songs have appeared, and a kindergarten has made a CD of the children singing. Besides these, a number of children’s songs appeared which have really caught on with the children. They include Á veg til dreymalands (On the way to dreamland) by Terji Rasmussen and Anker Eli Petersen, and Syngja sama lag (Sing the same song) by Ólav Jacobsen. Several are sung in schools and other groups, but have not appeared on CDs, such as Sleðurokk (Toboggan rock) by Regin Paturson.

In the last few years a group who call themselves “Kular Røtur” (“Cool Guys”) from Klaksvík have attracted a lot of attention with three new CDs. The very newest arrival is Brandur Enni, aged only thirteen, whose songs are really for teenagers rather than children.

It is a good question which directions Faroese children’s songs will take in the future. Will children sing Faroese songs, or will they choose lyrics in English from MTV? Does it matter at all whether children and adults sing? Some people believe that singing lessons in primary schools will die out, but can this be true? I am optimistic about the future, because surely our own language must be closest to our hearts? Texts and melodies change, quite naturally, which is right and proper – everything develops and changes in time. And that is certainly true of Faroese children’s songs.

Pauli Hansen

The Christmas Seal 2003

Jólatrøll

The sheet of Christmas seals 2003 shows 30 different patterns for boatmen’s jerseys. The pattern around the edge of the sheet is called the “ring dance”.

As usual, the profit of the sale goes to The Christmas Seal Foundation, which supports children- and youth work in the Faroe Islands.

Parts of the material in this brochure have been taken from the book “Føroysk Bindingarmynstur” (Faroese Knitting Patterns). © Føroyskt Heimavirki

“Jólatrøll” means commenced work (for example knitwork) that a person has not managed to finish in time for Christmas. It was regarded as a great disgrace for the person in question. The half-finished work was hung on display in the “roykstova” (the workroom and living room) of the farm to expose the person in question to public derision.

The term “Juletrold” is still used on the Faroe Islands.

The talented young artist who has designed this year’s Christmas seals is Edward Fuglø, who also designed the seals in 1997, 1999 and 2001.

Edward was born (in 1965) and grew up in Klaksvík, where he has now established himself as a professional artist who repeatedly surprises us with his creative originality and versatile neo-realistic style.

Trained at the Danish School of Art and Design (1987-1991), his artistic talent embraces several genres. Scenography, costume design, painting, book and stamp illustration – just to give some examples. In 2001 Edward Fuglø was awarded the Nordic Children’s Book Prize for his work.

Most linguists agree that the name “Færøerne” (the Faroe Islands) means fåreøerne (sheep islands). In Faroese, the word “seyður” (isl. sauður, no. sau / saud) is used in the same sense as the word “får” (sheep), which is the common term in the Eastern Nordic language area, i.e. in Danish and Swedish.

In the Old Norse language, the islands were called “Færeyjar”, a name that, according to oral tradition, they were reportedly given because of the many sheep that existed on the islands already when the first Norsemen arrived.

Before the Faroese acquired ships and became engaged in sea fishery, the Faroe Islands was a peasant society that was fairly isolated from the surrounding world. The society was based on fishing with open boats and sheep breeding. Sheep were of particular importance, as they provided both meat and wool.

There is an old Faroese saying that “ull er Føroya gull” (wool is Faroese gold), and, as an excellent example of the truth of this saying, it can be mentioned that the most important export article to Denmark in the 17th and 18th centuries was knitted socks.

Virtually all clothing was made of sheepswool. The clothes were both woven and knitted. Especially in connection with knitting, there were many different patterns for both men and women. Even underwear came in many different patterns. The men’s jerseys for use on the sea could have many different patterns, and this was, of course, also true of women’s jerseys. Patterns for borders were also available in many versions. Documents from the 17th century show that the use of patterns was common at the time, but, around a hundred years ago, the custom of knitting patterned jerseys was disappearing in line with plain jerseys becoming increasingly popular.

Around 1915, the librarian M.A. Jacobsen and the farmer in the village of Skælingur, Jógvan á Skælingi, met in Tórshavn. During their conversation, they started talking about old customs that were dying out, for example the old knitting patterns. They agreed that Jógvan was to try to gather old patterns in the northern part of Streymoy.

He got hold of thirty patterns. He acquired most of them in the village of Leynar from Rakul Egholm, who also knitted a long white jersey sleeve for him with all the patterns in purple. All these patterns with the accompanying names were donated to the Faroese museum Føroya Forngripagoymsla in 1921. They were part of a sales exhibition in 1927 in connection with Sankt Olai, the Faroese national day.

The second time the patterns were exhibited was at the Institute of Technology in Copenhagen. The many visitors included Queen Alexandrine, who was greatly impressed and who asked the tailor Hans M. Debes, who was also present, whether she could buy these patterns. As this was not possible, she asked him to try to have them published.

The result of this was that Hans Marius Debes, who had great respect for old Faroese culture, travelled around the islands to gather knitting patterns. He succeeded in gathering more than a hundred patterns in addition to the above thirty patterns, and the book “Føroysk bindingarmynstur” (Faroese Knitting Patterns) was published in 1932.

He primarily acquired the patterns from old worn-out garments, so it was probably at the last minute that the knitting patterns were published because people had long been knitting clothes without hardly any use of patterns.

We probably cannot say that all the patterns are of Faroese origin, but they feel so personal and familiar with names that are attached to appearance, village, place or woman that they have gradually become national property and part of the national heritage.

Hans M. Debes dedicated his book to Her Royal Highness, Queen Alexandrine, in deferential gratitude for her support and encouragement to gather these patterns.

The 30 patterns on the sheet are shown below

Eyðunsstovumynstrið, Audun’s / Eiden’s + living room = house + the pattern

Skankarnir, The shanks

Billumynstur, Sibylla’s pattern

Gomlustovumynstur, Old + living room = house + pattern

Bløðini, The leaves

Krókarnir, The hooks / corners

Kettunøsin, The cat’s nose

Pikkini, The dots

Gásareygað, The goose eye

Lítla skák og teinur, Small oblique stroke and small stripe

Katrinarmynstur, Katrine’s / Karen’s pattern

Rokkarnir, The spinning wheels

Havbylgjan, The sea wave

Dagur og nátt, Day and night

Lítla skák aftur og fram, Small oblique stroke backwards and forwards

Skjøldrarnir, The gables

Puntarnir, The points / spots / dots

Hundagongan, The pack of dogs

Krúnan, The crown

Naddarnir, Difficult to provide a brief translation of this

Heila stjørna, Whole star

Rossagronin, “Horse face”

Rútarnir, The squares

Gásaryggur, Goose back

Kollafjarðarskákið, Kollefjord’s oblique strok

Barbustovumynstrið, Barbara’s + living room = house + the pattern

Krossarnir, The crosses

Skákapikkið, Oblique dots

Blóman, Floral

The translation is subject to reservations. A lengthy explanation is often needed. Many of the words have several meanings, and it is often impossible to say which meaning is the correct one or how a name is to be understood.

The sheet of Christmas seals 2003 shows 30 different patterns for boatmen’s jerseys. The pattern around the edge of the sheet is called the “ring dance”.

As usual, the profit of the sale goes to The Christmas Seal Foundation, which supports children- and youth work in the Faroe Islands.

Parts of the material in this brochure have been taken from the book “Føroysk Bindingarmynstur” (Faroese Knitting Patterns). © Føroyskt Heimavirki

“Jólatrøll” means commenced work (for example knitwork) that a person has not managed to finish in time for Christmas. It was regarded as a great disgrace for the person in question. The half-finished work was hung on display in the “roykstova” (the workroom and living room) of the farm to expose the person in question to public derision.

The term “Juletrold” is still used on the Faroe Islands.

The talented young artist who has designed this year’s Christmas seals is Edward Fuglø, who also designed the seals in 1997, 1999 and 2001.

Edward was born (in 1965) and grew up in Klaksvík, where he has now established himself as a professional artist who repeatedly surprises us with his creative originality and versatile neo-realistic style.

Trained at the Danish School of Art and Design (1987-1991), his artistic talent embraces several genres. Scenography, costume design, painting, book and stamp illustration – just to give some examples. In 2001 Edward Fuglø was awarded the Nordic Children’s Book Prize for his work.

Most linguists agree that the name “Færøerne” (the Faroe Islands) means fåreøerne (sheep islands). In Faroese, the word “seyður” (isl. sauður, no. sau / saud) is used in the same sense as the word “får” (sheep), which is the common term in the Eastern Nordic language area, i.e. in Danish and Swedish.

In the Old Norse language, the islands were called “Færeyjar”, a name that, according to oral tradition, they were reportedly given because of the many sheep that existed on the islands already when the first Norsemen arrived.

Before the Faroese acquired ships and became engaged in sea fishery, the Faroe Islands was a peasant society that was fairly isolated from the surrounding world. The society was based on fishing with open boats and sheep breeding. Sheep were of particular importance, as they provided both meat and wool.

There is an old Faroese saying that “ull er Føroya gull” (wool is Faroese gold), and, as an excellent example of the truth of this saying, it can be mentioned that the most important export article to Denmark in the 17th and 18th centuries was knitted socks.

Virtually all clothing was made of sheepswool. The clothes were both woven and knitted. Especially in connection with knitting, there were many different patterns for both men and women. Even underwear came in many different patterns. The men’s jerseys for use on the sea could have many different patterns, and this was, of course, also true of women’s jerseys. Patterns for borders were also available in many versions. Documents from the 17th century show that the use of patterns was common at the time, but, around a hundred years ago, the custom of knitting patterned jerseys was disappearing in line with plain jerseys becoming increasingly popular.

Around 1915, the librarian M.A. Jacobsen and the farmer in the village of Skælingur, Jógvan á Skælingi, met in Tórshavn. During their conversation, they started talking about old customs that were dying out, for example the old knitting patterns. They agreed that Jógvan was to try to gather old patterns in the northern part of Streymoy.

He got hold of thirty patterns. He acquired most of them in the village of Leynar from Rakul Egholm, who also knitted a long white jersey sleeve for him with all the patterns in purple. All these patterns with the accompanying names were donated to the Faroese museum Føroya Forngripagoymsla in 1921. They were part of a sales exhibition in 1927 in connection with Sankt Olai, the Faroese national day.

The second time the patterns were exhibited was at the Institute of Technology in Copenhagen. The many visitors included Queen Alexandrine, who was greatly impressed and who asked the tailor Hans M. Debes, who was also present, whether she could buy these patterns. As this was not possible, she asked him to try to have them published.

The result of this was that Hans Marius Debes, who had great respect for old Faroese culture, travelled around the islands to gather knitting patterns. He succeeded in gathering more than a hundred patterns in addition to the above thirty patterns, and the book “Føroysk bindingarmynstur” (Faroese Knitting Patterns) was published in 1932.

He primarily acquired the patterns from old worn-out garments, so it was probably at the last minute that the knitting patterns were published because people had long been knitting clothes without hardly any use of patterns.

We probably cannot say that all the patterns are of Faroese origin, but they feel so personal and familiar with names that are attached to appearance, village, place or woman that they have gradually become national property and part of the national heritage.

Hans M. Debes dedicated his book to Her Royal Highness, Queen Alexandrine, in deferential gratitude for her support and encouragement to gather these patterns.

The 30 patterns on the sheet are shown below

Eyðunsstovumynstrið, Audun’s / Eiden’s + living room = house + the pattern

Skankarnir, The shanks

Billumynstur, Sibylla’s pattern

Gomlustovumynstur, Old + living room = house + pattern

Bløðini, The leaves

Krókarnir, The hooks / corners

Kettunøsin, The cat’s nose

Pikkini, The dots

Gásareygað, The goose eye

Lítla skák og teinur, Small oblique stroke and small stripe

Katrinarmynstur, Katrine’s / Karen’s pattern

Rokkarnir, The spinning wheels

Havbylgjan, The sea wave

Dagur og nátt, Day and night

Lítla skák aftur og fram, Small oblique stroke backwards and forwards

Skjøldrarnir, The gables

Puntarnir, The points / spots / dots

Hundagongan, The pack of dogs

Krúnan, The crown

Naddarnir, Difficult to provide a brief translation of this

Heila stjørna, Whole star

Rossagronin, “Horse face”

Rútarnir, The squares

Gásaryggur, Goose back

Kollafjarðarskákið, Kollefjord’s oblique strok

Barbustovumynstrið, Barbara’s + living room = house + the pattern

Krossarnir, The crosses

Skákapikkið, Oblique dots

Blóman, Floral

The translation is subject to reservations. A lengthy explanation is often needed. Many of the words have several meanings, and it is often impossible to say which meaning is the correct one or how a name is to be understood.

|

All Issues Copyright Posta, www.stamps.fo

|