2006

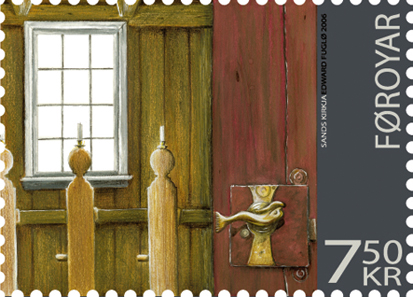

The church in Sandur

Date Of Issue 18.09.2006

Date Of Issue 18.09.2006

The First Church in the Faroes

It is hard to tell, where the first Faroese church was built. According to local tradition, the so-called “Sigmundarsteinur” (Sigmund’s Stone) on the island “Skúvoy” was a part of the church which was built by the Viking chief Sigmundur Brestisson. It was Sigmundur who brought Christianity to the Faroe Islands.

The Churches of Sandur

The oldest Faroese church we know of, is in the village of Sandur on the island of Sandoy. During an excavation below the present church in Sandur, the archaeologists found relics from not less than five older churches.

In the lowest layer there were pole-holes, a stone floor and a foundation stone from a stave church, which seems to be from the earliest days of Faroese Christianity, i. e. about year 1000 AD. The nave of the church was 5 x 4 metres and the choir was 2.5 x 2 metres. The entrance was in the western end of the church.

The Second Church

The second church was a bit larger than the first one. This was also a stave church, but covered with a stone wall at every side, except at the western house end. The church was built in the same way as the Greenlandic Middle Age churches from the 11th - 13th century, and is believed to date from that period. In this church several artefacts from the Catholic era were found, among others a holy water stoup made of stone, a censer made of bronze and a small oil lamp made of tuff.

Below the wooden floor, the archaeologists found 26 graves from the Middle Ages. There were both men, women and children among the buried, and it is therefore assumed that this was a privately owned church, and the dead bodies are from the family who owned the church. Several coins were also found, 33 of them from the period when the church was still in use. Most of the coins were Norwegian and derived from the period 1220 AD to 1300 AD.

It was in this second church where the infamous priest “Kálvur lítli” (Little Calf) worked.

The Third Church

The third church was built about year 1600 AD and was still standing in 1709 – 10, where it was mentioned in a report where all the Faroese churches are mentioned.

In this third church, another notorious vicar, “Harra Klæmint” (Clemen Laugesen Follerup from Jutland, Denmark) worked. It is said about him, that he easily carried his entire earthly belongings on his back when he arrived on the Faroes, but when he died he was the greatest landowner on the islands. The stories about his greed still live among the Faroese, and he rarely acquired his estates through fair play. “Harra Klæmint” had 23 children when he died.

The Fourth Church

The fourth church was built shortly after year 1710 AD, and this was the first church with an entrance hall. In this church a son of “Harra Pætur”, Peder Clemensen, worked. According to the tradition, he was considerably more sympathetic than his father.

The Fifth Church

In 1763 another new church was built. There is not much to tell about this church, other than that it was larger than the previous and also had an entrance hall and a choir.

The Sixth Church

In 1839 a new church was built again, this time even larger and with a belfry. This church stood until 1988, when a part of it it unfortunately burned in a deliberately started fire. It was rebuilt and the present church is an exact replica of the church from 1839.

The Coin Find

One day in 1863, the local sheriff M. A. Winther walked along the graveyard, where some men were about to dig a grave. He spotted something in the soil, which turned out to be the only significant hoard of coins found on the Faroes. There were 98 coins from the period between year 1000 and 1090 AD, i. e. from the era of the first stave church. A closer inspection showed that the coins were not buried in the church itself, but in a residential house close to the church. The coins came from Ireland, England, Germany, Hungary, Norway and Sweden.

It is hard to tell, where the first Faroese church was built. According to local tradition, the so-called “Sigmundarsteinur” (Sigmund’s Stone) on the island “Skúvoy” was a part of the church which was built by the Viking chief Sigmundur Brestisson. It was Sigmundur who brought Christianity to the Faroe Islands.

The Churches of Sandur

The oldest Faroese church we know of, is in the village of Sandur on the island of Sandoy. During an excavation below the present church in Sandur, the archaeologists found relics from not less than five older churches.

In the lowest layer there were pole-holes, a stone floor and a foundation stone from a stave church, which seems to be from the earliest days of Faroese Christianity, i. e. about year 1000 AD. The nave of the church was 5 x 4 metres and the choir was 2.5 x 2 metres. The entrance was in the western end of the church.

The Second Church

The second church was a bit larger than the first one. This was also a stave church, but covered with a stone wall at every side, except at the western house end. The church was built in the same way as the Greenlandic Middle Age churches from the 11th - 13th century, and is believed to date from that period. In this church several artefacts from the Catholic era were found, among others a holy water stoup made of stone, a censer made of bronze and a small oil lamp made of tuff.

Below the wooden floor, the archaeologists found 26 graves from the Middle Ages. There were both men, women and children among the buried, and it is therefore assumed that this was a privately owned church, and the dead bodies are from the family who owned the church. Several coins were also found, 33 of them from the period when the church was still in use. Most of the coins were Norwegian and derived from the period 1220 AD to 1300 AD.

It was in this second church where the infamous priest “Kálvur lítli” (Little Calf) worked.

The Third Church

The third church was built about year 1600 AD and was still standing in 1709 – 10, where it was mentioned in a report where all the Faroese churches are mentioned.

In this third church, another notorious vicar, “Harra Klæmint” (Clemen Laugesen Follerup from Jutland, Denmark) worked. It is said about him, that he easily carried his entire earthly belongings on his back when he arrived on the Faroes, but when he died he was the greatest landowner on the islands. The stories about his greed still live among the Faroese, and he rarely acquired his estates through fair play. “Harra Klæmint” had 23 children when he died.

The Fourth Church

The fourth church was built shortly after year 1710 AD, and this was the first church with an entrance hall. In this church a son of “Harra Pætur”, Peder Clemensen, worked. According to the tradition, he was considerably more sympathetic than his father.

The Fifth Church

In 1763 another new church was built. There is not much to tell about this church, other than that it was larger than the previous and also had an entrance hall and a choir.

The Sixth Church

In 1839 a new church was built again, this time even larger and with a belfry. This church stood until 1988, when a part of it it unfortunately burned in a deliberately started fire. It was rebuilt and the present church is an exact replica of the church from 1839.

The Coin Find

One day in 1863, the local sheriff M. A. Winther walked along the graveyard, where some men were about to dig a grave. He spotted something in the soil, which turned out to be the only significant hoard of coins found on the Faroes. There were 98 coins from the period between year 1000 and 1090 AD, i. e. from the era of the first stave church. A closer inspection showed that the coins were not buried in the church itself, but in a residential house close to the church. The coins came from Ireland, England, Germany, Hungary, Norway and Sweden.

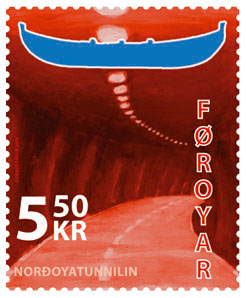

The Norðoya Tunnel

Date Of Issue 12.06.2006

Date Of Issue 12.06.2006

e tunnel – the way to the future

Some people have always tried to extend boundaries, although others feel safest inside well-defined limits.

Hans Christian Andersen’s 200th birthday was celebrated recently, and in his day, with the means of transport available at the time, the world was far larger and presented a much greater challenge than the world of today. Yet he is remembered for the maxim: “To travel is to live!” He took advantage of this urge and satisfied it on the one hand by getting to know the world around him with its different cultures, and by getting to know himself on the other. On his travels he gathered inspiration for his life and his writings. He became international – without being conscious of it himself.

Nowadays perhaps we say conversely: “In order to live, it is necessary to travel!” Time is money! From that point of view the tunnel is both necessary and practical. It facilitates access to the future. The advantages of modern technology are enhanced for the business world as well as for society as a whole. The day’s programme can be planned out differently – people are more free – and can more easily come and go as they choose without delays and detours.

But this freedom also carries with it a responsibility for planning the time to benefit your company, society, yourself and the entire world in your thoughts. Where do you go for entertainment? Close to home? Or way out of town? Does your town have anything special to offer in the way of entertainment? Can it provide enough to satisfy the young people? Or is the tunnel a good route to “the world of dreams”?

At this point the challenge lies in finding the right balance between on the contrasting possibilities of providing something for every individual and of confining oneself within the limits of the town.

We should exploit the tunnel as a useful route to all-round development and the challenge here becomes exciting as well as necessary. We are linked to the centres of activities – and they are linked to us. We need to listen to common sense to reap the best advantages from this tunnel.

One thing is certain, however! As far as Klaksvík, on the island of Borðoy, is concerned, the tunnel is the biggest and most significant development in living memory, as the future will confirm in full. The tunnel is part of the process of internationalisation.

Facts about the tunnel

The specific plans for a tunnel to connect the island of Eysturoy and the island of Borðoy are not entirely new. In 1988 Landsverkfrøðingurin (the national engineer) carried out a number of seismic investigations in Leirvíksfjørður (the strait between the two islands). A year earlier, an engineer had drawn up an overall plan showing alternative sites for constructing tunnels.

Further surveys in 1988 confirmed that the tunnel plans were considered to be economically viable. Fifteen years after the first surveys, work began on boring the tunnel between Eysturoy and Borðoy.

The tunnel is 6.3 km long and goes down to a depth of 150 metres below sea level. The maximum gradient will be about 6 per cent.

If all goes according to plan, the tunnel will be opened on 29 April 2006.

Some people have always tried to extend boundaries, although others feel safest inside well-defined limits.

Hans Christian Andersen’s 200th birthday was celebrated recently, and in his day, with the means of transport available at the time, the world was far larger and presented a much greater challenge than the world of today. Yet he is remembered for the maxim: “To travel is to live!” He took advantage of this urge and satisfied it on the one hand by getting to know the world around him with its different cultures, and by getting to know himself on the other. On his travels he gathered inspiration for his life and his writings. He became international – without being conscious of it himself.

Nowadays perhaps we say conversely: “In order to live, it is necessary to travel!” Time is money! From that point of view the tunnel is both necessary and practical. It facilitates access to the future. The advantages of modern technology are enhanced for the business world as well as for society as a whole. The day’s programme can be planned out differently – people are more free – and can more easily come and go as they choose without delays and detours.

But this freedom also carries with it a responsibility for planning the time to benefit your company, society, yourself and the entire world in your thoughts. Where do you go for entertainment? Close to home? Or way out of town? Does your town have anything special to offer in the way of entertainment? Can it provide enough to satisfy the young people? Or is the tunnel a good route to “the world of dreams”?

At this point the challenge lies in finding the right balance between on the contrasting possibilities of providing something for every individual and of confining oneself within the limits of the town.

We should exploit the tunnel as a useful route to all-round development and the challenge here becomes exciting as well as necessary. We are linked to the centres of activities – and they are linked to us. We need to listen to common sense to reap the best advantages from this tunnel.

One thing is certain, however! As far as Klaksvík, on the island of Borðoy, is concerned, the tunnel is the biggest and most significant development in living memory, as the future will confirm in full. The tunnel is part of the process of internationalisation.

Facts about the tunnel

The specific plans for a tunnel to connect the island of Eysturoy and the island of Borðoy are not entirely new. In 1988 Landsverkfrøðingurin (the national engineer) carried out a number of seismic investigations in Leirvíksfjørður (the strait between the two islands). A year earlier, an engineer had drawn up an overall plan showing alternative sites for constructing tunnels.

Further surveys in 1988 confirmed that the tunnel plans were considered to be economically viable. Fifteen years after the first surveys, work began on boring the tunnel between Eysturoy and Borðoy.

The tunnel is 6.3 km long and goes down to a depth of 150 metres below sea level. The maximum gradient will be about 6 per cent.

If all goes according to plan, the tunnel will be opened on 29 April 2006.

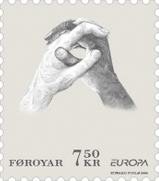

Europa 2006 – Integration

Date Of Issue 12.06.2006

Date Of Issue 12.06.2006

Integration

Each year the European postal collaboration under the auspices of PostEurop makes arrangements to publish joint European postage stamps with varying themes. This year's European stamps have “Young People and Integration” as their common theme.

Over the past few decades, immigration from third-world countries has presented the established societies in Europe with considerable challenges. In spite of the best intentions where peaceful integration is concerned, the difficulties have proved to be greater than anticipated. Culture, language, and not least religion, have turned out to be more of a hindrance than most people might have imagined just one or perhaps two generations ago.

The word 'integration' comes from Latin, and means acceptance (into a community) or gathering (into a unity or a whole). Such a unity is only possible in a future perspective and therefore belongs to the young.

Young people are quite prepared to associate with newcomers. There are many foreigners who are members of our sports associations, for example, where they are very welcome. They bring inspiration and knowledge to Faroese sport.

This gives food for thought concerning the great difficulties that the Faroese authorities are capable of causing what are in reality the very few foreigners who choose to live in the Faroes.

The older generation is much more likely to take a restrictive attitude to new citizens than are young people.

Young people of today take a more relaxed view of their native culture. They travel around the world freely and want to experience foreign customs and cultures. And they have no experience of the old Faroese society, which is now a thing of the past. They do not feel the loss that the older generation feels more or less acutely. And modern youngsters have grown up with the Internet so they can travel virtually all over the world – every day.

Older people talk about hospitality when the discussion turns to immigrants. In the old days, hospitality was almost a characteristic quality of Faroese culture. A number of phrases express this attitude. A poet puts it as follows, "Tá stongd var ei bóndans stova, um ókunnufólk kom á leið." (Then, the farmer's door was not locked when strangers came by). Foreign accounts of travelling in the Faroes, old as well as new, often mention how hospitable the Faroese are. They also suggest that rich and poor alike should be treated equally where hospitality is concerned. We gain a view of a society in which residents are equals and everybody is of equal value.

But hospitality and integration are not the same. Guests go back home again. Immigrants settle in their new country. They are not guests, but residents. This is where older people's ideas of hospitality begin to fail. Integration is not simply a question of others adapting to our society. It is a mutual process, and this makes things far more difficult. But this is precisely where the real challenge lies in Europe today. There can be no doubt that the same challenge will make itself felt in the Faroes.

Young people today hardly see integration as a threat. They do not share the view of hospitality that was current in the past. This implies an idea of reality that divides people into "us" and "them" (the strangers who we must show hospitality), which appears to be in decline. Older people really see people from other countries as strangers, whereas young people do not feel they are so different. The old idea of hospitality makes an undesirable distinction between "us" and "guests".

For the present, it is not possible to talk about immigration of any extent in the Faroes. And, in the meantime, we can reflect over our own, internal integration. Are all Faroese integrated into Faroese society? What about the people with physical handicaps, who are unable to enter schools and other public buildings? The reason may often be as banal as a staircase or a door that is slightly too narrow. A handicap can rob people of every opportunity, even though very little may be necessary to improve these opportunities. People may be obliged to stay in their homes simply because a kerb is too high. We avoid people with mental illnesses and build institutions where we can hide them away. They must be integrated yet again.

The discussion on immigrants and integration has made this issue of internal integration more topical and created more understanding of the need to improve conditions for our own, silent, non-integrated people. While we await the arrival of more immigrants, it would be appropriate for us to sweep in front of our own door.

Each year the European postal collaboration under the auspices of PostEurop makes arrangements to publish joint European postage stamps with varying themes. This year's European stamps have “Young People and Integration” as their common theme.

Over the past few decades, immigration from third-world countries has presented the established societies in Europe with considerable challenges. In spite of the best intentions where peaceful integration is concerned, the difficulties have proved to be greater than anticipated. Culture, language, and not least religion, have turned out to be more of a hindrance than most people might have imagined just one or perhaps two generations ago.

The word 'integration' comes from Latin, and means acceptance (into a community) or gathering (into a unity or a whole). Such a unity is only possible in a future perspective and therefore belongs to the young.

Young people are quite prepared to associate with newcomers. There are many foreigners who are members of our sports associations, for example, where they are very welcome. They bring inspiration and knowledge to Faroese sport.

This gives food for thought concerning the great difficulties that the Faroese authorities are capable of causing what are in reality the very few foreigners who choose to live in the Faroes.

The older generation is much more likely to take a restrictive attitude to new citizens than are young people.

Young people of today take a more relaxed view of their native culture. They travel around the world freely and want to experience foreign customs and cultures. And they have no experience of the old Faroese society, which is now a thing of the past. They do not feel the loss that the older generation feels more or less acutely. And modern youngsters have grown up with the Internet so they can travel virtually all over the world – every day.

Older people talk about hospitality when the discussion turns to immigrants. In the old days, hospitality was almost a characteristic quality of Faroese culture. A number of phrases express this attitude. A poet puts it as follows, "Tá stongd var ei bóndans stova, um ókunnufólk kom á leið." (Then, the farmer's door was not locked when strangers came by). Foreign accounts of travelling in the Faroes, old as well as new, often mention how hospitable the Faroese are. They also suggest that rich and poor alike should be treated equally where hospitality is concerned. We gain a view of a society in which residents are equals and everybody is of equal value.

But hospitality and integration are not the same. Guests go back home again. Immigrants settle in their new country. They are not guests, but residents. This is where older people's ideas of hospitality begin to fail. Integration is not simply a question of others adapting to our society. It is a mutual process, and this makes things far more difficult. But this is precisely where the real challenge lies in Europe today. There can be no doubt that the same challenge will make itself felt in the Faroes.

Young people today hardly see integration as a threat. They do not share the view of hospitality that was current in the past. This implies an idea of reality that divides people into "us" and "them" (the strangers who we must show hospitality), which appears to be in decline. Older people really see people from other countries as strangers, whereas young people do not feel they are so different. The old idea of hospitality makes an undesirable distinction between "us" and "guests".

For the present, it is not possible to talk about immigration of any extent in the Faroes. And, in the meantime, we can reflect over our own, internal integration. Are all Faroese integrated into Faroese society? What about the people with physical handicaps, who are unable to enter schools and other public buildings? The reason may often be as banal as a staircase or a door that is slightly too narrow. A handicap can rob people of every opportunity, even though very little may be necessary to improve these opportunities. People may be obliged to stay in their homes simply because a kerb is too high. We avoid people with mental illnesses and build institutions where we can hide them away. They must be integrated yet again.

The discussion on immigrants and integration has made this issue of internal integration more topical and created more understanding of the need to improve conditions for our own, silent, non-integrated people. While we await the arrival of more immigrants, it would be appropriate for us to sweep in front of our own door.

The Christmas Seal 2006

Christmas Bakery

The motifs on the 2006 Christmas seals are cakes and biscuits drawn by the artist Edward Fuglø. The idea came almost automatically, because baking is simply part of Christmas. Some of these cakes and cookies are only ever baked at Christmas time, so they radiate Christmas spirit.

We all love to be hospitable at Christmas and have something to offer visitors who drop in. You are practically certain to be offered a cup of coffee and biscuits when-ever you visit friends and relations.

There is still a very strong tradition on the Faroes that it brings bad luck to “carry Christmas out” after visiting a house, so it is considered bad manners to leave without tasting what is offered.

The motifs on the 2006 Christmas seals are cakes and biscuits drawn by the artist Edward Fuglø. The idea came almost automatically, because baking is simply part of Christmas. Some of these cakes and cookies are only ever baked at Christmas time, so they radiate Christmas spirit.

We all love to be hospitable at Christmas and have something to offer visitors who drop in. You are practically certain to be offered a cup of coffee and biscuits when-ever you visit friends and relations.

There is still a very strong tradition on the Faroes that it brings bad luck to “carry Christmas out” after visiting a house, so it is considered bad manners to leave without tasting what is offered.

All Issues Copyright Posta, www.stamps.fo