2005

The Faroese Hare

Date Of Issue 18.04.2005

Date Of Issue 18.04.2005

Hares live in woods and on moors, and the female, called the doe, leaves her leverets hiding in hollows called forms between stones and rocks, while she searches for food. The Faroese “snow hare” (Lepus timidus) becomes greyish white in winter nowadays, and not snow white, like its ancestors who were introduced into the Faroes in 1855. The hares of today are “blue hares” like those in Scotland.

The original Canadian polar hare (Lepus arcticus) is found in Greenland. The biology of this species is similar to that of the northern European snow hare. Polar hares and snow hares are both 46-61 cm long and weigh 3.5-4.2 kg (about 4-9 lb). In Greenland they tend to be larger the further north they live. Both types have short, wide ears with black tips.

Polar hares turn completely white in the winter, but there are two varieties of snow hares. On the Faroes, in Scotland (including the Isles), and in Ireland, Sweden and southern Norway there are blue hares with a greyish white winter coat. In the rest of Norway their winter coat is snow white, while in the summer both varieties have brown or light greyish brown coats.

Hares are widespread in northern countries, but there are no hares in Iceland. Snow hares are found on the Faroes, in Scotland (and on the Isles), in Ireland and Norway and in the Alps, and they are common on many of the Faroe Islands. Polar hares are found in northern coastal regions in Canada and Greenland, but not around Melville Bay and in South east Greenland. Archaeologists have found remains of the bones of hares in the Northmen’s medieval settlements.

Four snow hares from Kragerøen in the Oslo fjord were introduced on the Faroes in August 1855 and released on the cliffs of Kirkjubøreyn west of Tórshavn. In the first winters they were completely white like snow hares, but as early as the 1860s the first greyish winter hares were seen, the so-called blue hares. Their numbers increased rapidly and they supplanted the white snow hares completely. The last completely white snow hare was shot in the winter of 1916-17.

Breeding tests with snow hares and blue hares have revealed that genetically, the white winter coat is always dominant. Kragerøen in particular is a borderline area with snow hares high up on the cliffs and blue hares lower down. If just one of the original four hares had carried the blue hare genes, the result would not be seen before the third generation at the earliest. But then the blue hares had all the advantages on the Faroes in the mild Atlantic winters.

Blue hares on the Faroes drop leverets three times a year, but it is by no means certain that the leverets from all three litters will survive. Snow hares on the other hand only have two litters, and their coats turn white relatively early in the autumn, while the blue hare’s winter coat appears later. Where the snow does not often lie for long, a snow hare cannot hide as easily from hunters as a blue hare.

When snow hares were moved to an area with a coastal climate, the advantages of the white winter coat became disadvantages. This was why only 60 years passed before the dominant snow hares were completely exterminated and replaced by animals with the recessive blue hare genes. It is simply a textbook example of natural selection and adaptation to the environment.

Polar hares and snow hares live in the woods where they can – or on heather-covered moors close to the snow line. The hares feed on various plants, grasses and sedges, (Carex), roots and ferns, supplementing them with leaf and flower shoots from bushes and trees. Polar hares and snow hares are most active at dusk, but in the mating season the bucks can be seen pursuing the does in broad daylight as well.

The does are pregnant for about seven weeks. Polar hares and the snow hares with completely white winter coats that live farthest north only breed once a year. Further south they have two litters a year, while the blue hares drop three litters a year consisting of two or three leverets each. All the same, the weather conditions are seldom so favourable that all the leverets survive. Polar hares in Greenland have five to seven leverets, which reach sexual maturity at eight months old. In other words, they can start breeding themselves when they are a year old.

Polar hares and snow hares are hunted for their delicious meat. It has been estimated that the population of hares on the Faroes was at least five thousand in 1997. However, it is very difficult to obtain accurate figures for the number of hares shot on the Faroes each year, because this is the only country in Northern Europe where hunters are not obliged to obtain a game licence. Hares may be hunted on the Faroes from 2 November until 31 December.

The original Canadian polar hare (Lepus arcticus) is found in Greenland. The biology of this species is similar to that of the northern European snow hare. Polar hares and snow hares are both 46-61 cm long and weigh 3.5-4.2 kg (about 4-9 lb). In Greenland they tend to be larger the further north they live. Both types have short, wide ears with black tips.

Polar hares turn completely white in the winter, but there are two varieties of snow hares. On the Faroes, in Scotland (including the Isles), and in Ireland, Sweden and southern Norway there are blue hares with a greyish white winter coat. In the rest of Norway their winter coat is snow white, while in the summer both varieties have brown or light greyish brown coats.

Hares are widespread in northern countries, but there are no hares in Iceland. Snow hares are found on the Faroes, in Scotland (and on the Isles), in Ireland and Norway and in the Alps, and they are common on many of the Faroe Islands. Polar hares are found in northern coastal regions in Canada and Greenland, but not around Melville Bay and in South east Greenland. Archaeologists have found remains of the bones of hares in the Northmen’s medieval settlements.

Four snow hares from Kragerøen in the Oslo fjord were introduced on the Faroes in August 1855 and released on the cliffs of Kirkjubøreyn west of Tórshavn. In the first winters they were completely white like snow hares, but as early as the 1860s the first greyish winter hares were seen, the so-called blue hares. Their numbers increased rapidly and they supplanted the white snow hares completely. The last completely white snow hare was shot in the winter of 1916-17.

Breeding tests with snow hares and blue hares have revealed that genetically, the white winter coat is always dominant. Kragerøen in particular is a borderline area with snow hares high up on the cliffs and blue hares lower down. If just one of the original four hares had carried the blue hare genes, the result would not be seen before the third generation at the earliest. But then the blue hares had all the advantages on the Faroes in the mild Atlantic winters.

Blue hares on the Faroes drop leverets three times a year, but it is by no means certain that the leverets from all three litters will survive. Snow hares on the other hand only have two litters, and their coats turn white relatively early in the autumn, while the blue hare’s winter coat appears later. Where the snow does not often lie for long, a snow hare cannot hide as easily from hunters as a blue hare.

When snow hares were moved to an area with a coastal climate, the advantages of the white winter coat became disadvantages. This was why only 60 years passed before the dominant snow hares were completely exterminated and replaced by animals with the recessive blue hare genes. It is simply a textbook example of natural selection and adaptation to the environment.

Polar hares and snow hares live in the woods where they can – or on heather-covered moors close to the snow line. The hares feed on various plants, grasses and sedges, (Carex), roots and ferns, supplementing them with leaf and flower shoots from bushes and trees. Polar hares and snow hares are most active at dusk, but in the mating season the bucks can be seen pursuing the does in broad daylight as well.

The does are pregnant for about seven weeks. Polar hares and the snow hares with completely white winter coats that live farthest north only breed once a year. Further south they have two litters a year, while the blue hares drop three litters a year consisting of two or three leverets each. All the same, the weather conditions are seldom so favourable that all the leverets survive. Polar hares in Greenland have five to seven leverets, which reach sexual maturity at eight months old. In other words, they can start breeding themselves when they are a year old.

Polar hares and snow hares are hunted for their delicious meat. It has been estimated that the population of hares on the Faroes was at least five thousand in 1997. However, it is very difficult to obtain accurate figures for the number of hares shot on the Faroes each year, because this is the only country in Northern Europe where hunters are not obliged to obtain a game licence. Hares may be hunted on the Faroes from 2 November until 31 December.

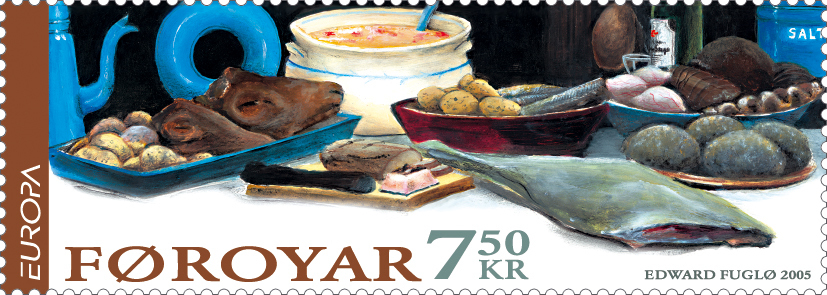

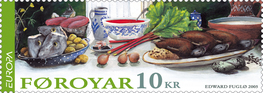

Europa 2005 – Gastronomy

Date Of Issue 18.04.2005

Date Of Issue 18.04.2005

All over the world the provision and preparation of food have always been an important part of national culture, with countless variations being shaped by the possibilities to hand.

Climate has been crucial in terms of the type of food it was possible to produce. Living in tropical countries and having to survive in the polar regions will always be different, of course.

The original food on the Faroes came for the most part from the animal population on the island, mainly sheep in the upland pastures, birds on the bird cliffs and fish in the sea. The climate is not the best for cultivating cereals, vegetables, etc., so they were not of great importance.

Potatoes did not become a regular ingredient in the daily diet until the late 19th century, although people had long been familiar with them. Instead they used to boil Faroese swedes (Brassica) for dinner, for example.

The seasons set their stamp on eating habits. Fish was more or less available all year round, but mostly in the spring, when it provided roe in addition to liver. The opportunity to eat other fresh food arrived at the same time as spring fishing (March – April). Cows usually calved in spring, so there was most milk in summer. Birding and egg collecting (nest plundering on the bird cliffs) were also part of the summer, while the chances of catching pilot whales are greatest in August, when people could also go out into the potato fields and pick new potatoes. In autumn the men went up into the mountains to bring the sheep in for slaughtering. Nearly every bit of a slaughtered sheep was put to good use. As well as the meat, people used the head, trotters, liver, lungs, heart, stomach and blood (the collective Faroese word for which is avroð).

Since ancient times the only way to keep most foodstuffs was to salt or dry them. Salt was in short supply for a long time, so drying was the commonest method for preserving food. There were two salting methods, pickling in brine and dry-curing, with barrels being used for both.

Meat, whale, fowl and fish were all dried. Once gutted, sheep were hung up to dry in the wind in a single piece. Before birds were hung up, they were split along the back and tied together in pairs. Fish too were hung up to dry in pairs, while whale meat was cut into loops before hanging.

The autumn weather had a major impact on whether what had been hung up to dry tasted right. The drying process itself can be divided into three stages: visnað (lightly dried), ræst (semi-dried/seasoned) and dried. These terms refer to flavour, appearance and smell. What we can call “lightly dried” is achieved in just a few days and is much faster for fish than for whale meat. The word visnað is not generally used about meat.

The change to ræst is slow, but if the air suddenly turns cold, whatever has been hung up to dry can jump this stage and never gets the real semi-dried/seasoned flavour. If, on the other hand, the air is too warm, the dried meat can become too ræst and so end up with a harsh or rank flavour. Meat is normally dried until Christmas.

Mutton, fish, fowl and whale meat are eaten at all three stages of the process (and fresh too, of course). Visnað and ræst have to be cooked. Dried meat is eaten as it is. For food to have the best possible flavour, it has to be treated correctly, of course. In particular you have to make sure that flies are kept away, especially in mild autumn weather, or there is a risk of the food being spoiled by maggots.

Mealtimes vary from country to country. In days gone by there were three main mealtimes on the Faroe Islands: morgunmatur (lunch) at around 9 – 10 am, døgurði (dinner) at around 2 – 3 pm and nátturði (supper) at 9 pm or later. Normally there were also two smaller mealtimes: ábit (breakfast), which people ate when they got up early in the morning, and millummáli (tea), which came between dinner and supper.

For lunch people used to eat drýlur (cylindrical, unleavened bread, originally baked in the embers of the fire). Later, rye bread made from rye and wheat flour became more common. An accompaniment would be served with the unleavened bread. These days it is sliced meats and the like, but back then it was most likely to be a piece of mutton.

Dinner usually consisted of boiled fish, whale meat and blubber or fowl. In the late 19th century it became common for people to eat potatoes for dinner. On Sundays and festivals those who could (i.e. farmers) would have ræst meat and súpan – soup, specifically meat soup (made from preserved meat with flour or grains, etc., added). Cooked fish was also considered to be a good Sunday meal.

Supper nearly always took the form of spoon food, i.e. milk products of various sorts in summer and soup in winter. When the cow had calved there would be ketilost, a cold dish of heat-thickened colostrum served with cinnamon and sugar. Drýlur and bread were not eaten with supper, but it was common to eat wind-dried fish before the soup. People generally drank water, milk, milk mixed with water, tea or coffee.

No one started the day’s work on an empty stomach. Breakfast was therefore a slice of drýlur and a drink of milk, a little soup or leftovers from the previous day’s supper.

For tea people drank milk, tea or coffee accompanied by a slice of bread or, occasionally, pancakes. White bread or cake has gradually become more common.

Food was generally boiled. Every household had at least two pots: one for oily or greasy food such as blubber, liver, etc., and one for everything else. There were three types of food bowl: a meat bowl, a fish bowl and a snyktrog (for greasy or oily food). As well as their pots, people also kept large ladles (sleiv), slotted spoons (soðspón) and various “sticks” for stirring porridge (greytarsneis) and whipping milk or cream (a milk beater or tyril) in their one-roomed hut, which served as kitchen, workshop, living room and bedroom.

Times have changed, with the result that we now eat a lot of food bought in shopping centres – most of it foreign. The Faroe islanders have acquired an international cuisine, with vegetables, fruit and spices being a normal part of everyday life. But old Faroese food is still eaten with great relish and is regarded as a real delicacy.

Climate has been crucial in terms of the type of food it was possible to produce. Living in tropical countries and having to survive in the polar regions will always be different, of course.

The original food on the Faroes came for the most part from the animal population on the island, mainly sheep in the upland pastures, birds on the bird cliffs and fish in the sea. The climate is not the best for cultivating cereals, vegetables, etc., so they were not of great importance.

Potatoes did not become a regular ingredient in the daily diet until the late 19th century, although people had long been familiar with them. Instead they used to boil Faroese swedes (Brassica) for dinner, for example.

The seasons set their stamp on eating habits. Fish was more or less available all year round, but mostly in the spring, when it provided roe in addition to liver. The opportunity to eat other fresh food arrived at the same time as spring fishing (March – April). Cows usually calved in spring, so there was most milk in summer. Birding and egg collecting (nest plundering on the bird cliffs) were also part of the summer, while the chances of catching pilot whales are greatest in August, when people could also go out into the potato fields and pick new potatoes. In autumn the men went up into the mountains to bring the sheep in for slaughtering. Nearly every bit of a slaughtered sheep was put to good use. As well as the meat, people used the head, trotters, liver, lungs, heart, stomach and blood (the collective Faroese word for which is avroð).

Since ancient times the only way to keep most foodstuffs was to salt or dry them. Salt was in short supply for a long time, so drying was the commonest method for preserving food. There were two salting methods, pickling in brine and dry-curing, with barrels being used for both.

Meat, whale, fowl and fish were all dried. Once gutted, sheep were hung up to dry in the wind in a single piece. Before birds were hung up, they were split along the back and tied together in pairs. Fish too were hung up to dry in pairs, while whale meat was cut into loops before hanging.

The autumn weather had a major impact on whether what had been hung up to dry tasted right. The drying process itself can be divided into three stages: visnað (lightly dried), ræst (semi-dried/seasoned) and dried. These terms refer to flavour, appearance and smell. What we can call “lightly dried” is achieved in just a few days and is much faster for fish than for whale meat. The word visnað is not generally used about meat.

The change to ræst is slow, but if the air suddenly turns cold, whatever has been hung up to dry can jump this stage and never gets the real semi-dried/seasoned flavour. If, on the other hand, the air is too warm, the dried meat can become too ræst and so end up with a harsh or rank flavour. Meat is normally dried until Christmas.

Mutton, fish, fowl and whale meat are eaten at all three stages of the process (and fresh too, of course). Visnað and ræst have to be cooked. Dried meat is eaten as it is. For food to have the best possible flavour, it has to be treated correctly, of course. In particular you have to make sure that flies are kept away, especially in mild autumn weather, or there is a risk of the food being spoiled by maggots.

Mealtimes vary from country to country. In days gone by there were three main mealtimes on the Faroe Islands: morgunmatur (lunch) at around 9 – 10 am, døgurði (dinner) at around 2 – 3 pm and nátturði (supper) at 9 pm or later. Normally there were also two smaller mealtimes: ábit (breakfast), which people ate when they got up early in the morning, and millummáli (tea), which came between dinner and supper.

For lunch people used to eat drýlur (cylindrical, unleavened bread, originally baked in the embers of the fire). Later, rye bread made from rye and wheat flour became more common. An accompaniment would be served with the unleavened bread. These days it is sliced meats and the like, but back then it was most likely to be a piece of mutton.

Dinner usually consisted of boiled fish, whale meat and blubber or fowl. In the late 19th century it became common for people to eat potatoes for dinner. On Sundays and festivals those who could (i.e. farmers) would have ræst meat and súpan – soup, specifically meat soup (made from preserved meat with flour or grains, etc., added). Cooked fish was also considered to be a good Sunday meal.

Supper nearly always took the form of spoon food, i.e. milk products of various sorts in summer and soup in winter. When the cow had calved there would be ketilost, a cold dish of heat-thickened colostrum served with cinnamon and sugar. Drýlur and bread were not eaten with supper, but it was common to eat wind-dried fish before the soup. People generally drank water, milk, milk mixed with water, tea or coffee.

No one started the day’s work on an empty stomach. Breakfast was therefore a slice of drýlur and a drink of milk, a little soup or leftovers from the previous day’s supper.

For tea people drank milk, tea or coffee accompanied by a slice of bread or, occasionally, pancakes. White bread or cake has gradually become more common.

Food was generally boiled. Every household had at least two pots: one for oily or greasy food such as blubber, liver, etc., and one for everything else. There were three types of food bowl: a meat bowl, a fish bowl and a snyktrog (for greasy or oily food). As well as their pots, people also kept large ladles (sleiv), slotted spoons (soðspón) and various “sticks” for stirring porridge (greytarsneis) and whipping milk or cream (a milk beater or tyril) in their one-roomed hut, which served as kitchen, workshop, living room and bedroom.

Times have changed, with the result that we now eat a lot of food bought in shopping centres – most of it foreign. The Faroe islanders have acquired an international cuisine, with vegetables, fruit and spices being a normal part of everyday life. But old Faroese food is still eaten with great relish and is regarded as a real delicacy.

All Issues Copyright Posta, www.stamps.fo