2012

Nordic Contemporary Art

Date Of Issue 24.09.2012

Date Of Issue 24.09.2012

Nordic contemporary art - paraphrases

A double paraphrase

The idea for the two Faroese stamps comes from Niels Halm, director of the Nordic House in Tórshavn, and gives Posta Stamps an opportunity to play a part in the exciting world of contemporary Nordic art. Normally, only stamps by Faroese artists are released in the Faroe Islands. This time, however, the two new stamps feature a Swede’s paraphrase of a Faroese artist’s work and vice versa, making this a groundbreaking joint Nordic project.

The 13 kr. stamp is entitled “Mr. Walker on the Faroe Island”, and was created by the Swedish artist, Jan Hafström (b. 1937). The motif is a man turned half away from the viewer, disguised with a hat and a pair of dark sunglasses. He does not particularly look like a countryside rambler, but rather a comic figure – perhaps a detective who arrived in the Faroe Islands from the big city, wearing a chequered trench coat. He faces a typical Faroese landscape, which in fact is a section of “Favorite Campingspot”, a 2008 painting by Faroese colleague Edward Fuglø, which is owned by Tórshavn Municipality. This is a so-called paraphrase, i.e. a free interpretation of another artist’s work. Is the man frozen in an attempt to understand the grandeur of nature? Is he viewing the painting by Fuglø in a museum? Or perhaps he is honing in on one of the small houses that was the site of a recent murder he has come to the Faroe Islands to solve? We don’t know and the question will never be resolved, but it is clear that he is a stranger to the Faroe Islands, giving this ambiguous motif an eerie tension.

The small, light-green houses are located between a road and a waterfall that flows milky-white over the edge of a cliff. The fell stops abruptly at a characteristic vertical cliff, as seen so often in the Faroe Islands. We cannot see the sea, because the man is blocking our view, but everyone who has experienced the Faroe Islands can envision it outside of the picture frame. When you fly to the Faroe Islands, the beautiful green, grass-covered islands suddenly appear in the middle of the giant North Atlantic. Everyone who is familiar with these fantastic islands knows how important it is to be careful not to fall over the edge of the many cliffs.

The mystical man is “Mr. Walker”, Jan Håfström’s alter ego, who also shares a resemblance to his father, a travelling salesman who was often absent in his childhood. Hafström mostly saw his father from behind, as he ventured out into the world. In the summer of 2011, this “Walker” made it to the Faroe Islands during the “Cosmic Sleepwalker” exhibition at the Nordic House. Here, Hafström exhibited with Knud Odde and he created a lithograph with the motif in Jan Andersson’s graphic workshop in Tórshavn.

Jan Hafström has received numerous awards and has represented his country four times at the prestigious Venice Biennale. He is considered Sweden's greatest living artist.

Edward Fuglø: Egg Procession

Edward Fuglø was born in the Faroe Islands in 1965. He is an imaginative, surrealistic artist who has renewed Faroese art with his original works, which are driven by equal parts subtle humour and social criticism. He lives and works in Klaksvig and is well represented at the Faroe Islands Art Museum, Listasavn Føroya.

His motif for the 21 kr. stamp is a bird egg – a recurring motif in his artistic work, which includes a range of media and sometimes also comes to expression in three dimensions. It is a giant bird egg that can be seen partly as a national symbol of bird hunting, which is so prevalent in the Faroe Islands, and partly as a symbol of fertility, nature and hope for the future. The large egg is carried by a monk in a cowl, who leads a procession of three other monks in cowls. Two of the monks are holding a burning torch so close to the egg that it has become red hot – perhaps to speed up the hatching? The last monk is holding a long stick in his hand. The monks’ faces are completely covered and they seem mysterious and somehow uncanny.

Edward Fuglø’s stamp motif is also a paraphrase of a work by his Swedish colleague Jan Hafström, who in the above mentioned exhibition at the Nordic House depicted these monks and also had a procession of dancers in cowls perform a dance choreographed by performance artist Lotta Melin. The cowl-clad dancers began by dancing around the Nordic House and then continued indoors. But whereas the figures in the performance carried a child’s coffin, referring to the most tragic death of all, Fuglø’s figures are life-affirming and humorous because of the oversized and unwieldy giant egg, which could hold a myriad of young birds. Thus, Edward Fulgø’s motif is a visually appealing cross-pollination of both artists’ works and a tribute to his Swedish colleague, who also paid similar tribute to Fuglø in the stamp featuring the Faroese landscape.

Lisbeth Bonde

Art critic and author

A double paraphrase

The idea for the two Faroese stamps comes from Niels Halm, director of the Nordic House in Tórshavn, and gives Posta Stamps an opportunity to play a part in the exciting world of contemporary Nordic art. Normally, only stamps by Faroese artists are released in the Faroe Islands. This time, however, the two new stamps feature a Swede’s paraphrase of a Faroese artist’s work and vice versa, making this a groundbreaking joint Nordic project.

The 13 kr. stamp is entitled “Mr. Walker on the Faroe Island”, and was created by the Swedish artist, Jan Hafström (b. 1937). The motif is a man turned half away from the viewer, disguised with a hat and a pair of dark sunglasses. He does not particularly look like a countryside rambler, but rather a comic figure – perhaps a detective who arrived in the Faroe Islands from the big city, wearing a chequered trench coat. He faces a typical Faroese landscape, which in fact is a section of “Favorite Campingspot”, a 2008 painting by Faroese colleague Edward Fuglø, which is owned by Tórshavn Municipality. This is a so-called paraphrase, i.e. a free interpretation of another artist’s work. Is the man frozen in an attempt to understand the grandeur of nature? Is he viewing the painting by Fuglø in a museum? Or perhaps he is honing in on one of the small houses that was the site of a recent murder he has come to the Faroe Islands to solve? We don’t know and the question will never be resolved, but it is clear that he is a stranger to the Faroe Islands, giving this ambiguous motif an eerie tension.

The small, light-green houses are located between a road and a waterfall that flows milky-white over the edge of a cliff. The fell stops abruptly at a characteristic vertical cliff, as seen so often in the Faroe Islands. We cannot see the sea, because the man is blocking our view, but everyone who has experienced the Faroe Islands can envision it outside of the picture frame. When you fly to the Faroe Islands, the beautiful green, grass-covered islands suddenly appear in the middle of the giant North Atlantic. Everyone who is familiar with these fantastic islands knows how important it is to be careful not to fall over the edge of the many cliffs.

The mystical man is “Mr. Walker”, Jan Håfström’s alter ego, who also shares a resemblance to his father, a travelling salesman who was often absent in his childhood. Hafström mostly saw his father from behind, as he ventured out into the world. In the summer of 2011, this “Walker” made it to the Faroe Islands during the “Cosmic Sleepwalker” exhibition at the Nordic House. Here, Hafström exhibited with Knud Odde and he created a lithograph with the motif in Jan Andersson’s graphic workshop in Tórshavn.

Jan Hafström has received numerous awards and has represented his country four times at the prestigious Venice Biennale. He is considered Sweden's greatest living artist.

Edward Fuglø: Egg Procession

Edward Fuglø was born in the Faroe Islands in 1965. He is an imaginative, surrealistic artist who has renewed Faroese art with his original works, which are driven by equal parts subtle humour and social criticism. He lives and works in Klaksvig and is well represented at the Faroe Islands Art Museum, Listasavn Føroya.

His motif for the 21 kr. stamp is a bird egg – a recurring motif in his artistic work, which includes a range of media and sometimes also comes to expression in three dimensions. It is a giant bird egg that can be seen partly as a national symbol of bird hunting, which is so prevalent in the Faroe Islands, and partly as a symbol of fertility, nature and hope for the future. The large egg is carried by a monk in a cowl, who leads a procession of three other monks in cowls. Two of the monks are holding a burning torch so close to the egg that it has become red hot – perhaps to speed up the hatching? The last monk is holding a long stick in his hand. The monks’ faces are completely covered and they seem mysterious and somehow uncanny.

Edward Fuglø’s stamp motif is also a paraphrase of a work by his Swedish colleague Jan Hafström, who in the above mentioned exhibition at the Nordic House depicted these monks and also had a procession of dancers in cowls perform a dance choreographed by performance artist Lotta Melin. The cowl-clad dancers began by dancing around the Nordic House and then continued indoors. But whereas the figures in the performance carried a child’s coffin, referring to the most tragic death of all, Fuglø’s figures are life-affirming and humorous because of the oversized and unwieldy giant egg, which could hold a myriad of young birds. Thus, Edward Fulgø’s motif is a visually appealing cross-pollination of both artists’ works and a tribute to his Swedish colleague, who also paid similar tribute to Fuglø in the stamp featuring the Faroese landscape.

Lisbeth Bonde

Art critic and author

Monsters

Date Of Issue 30.04.2012

Date Of Issue 30.04.2012

The old folklore often deals with issues on the borders between the known universe and a threatening outher world which people feared - or between right and wrong, defined by secular regulation and laws or by common tradition.

The conceptions about the ”Niðagrísur” (The Child Ghost) derive from a serious crime. The fact that the ”Grýla” (The Monster) goes for the children, derives from the need to observe ecclesiastical orders. The Beach Trolls keep the children away from the beach and thereby great danger – and the conceptions about the Mare is a symtom of physical and mental stress, which most people experience during their lifetime.

The bogeyman – scary disguise

Celebrations involving dressing up in various disguises are a feature of cultures throughout the world, including Denmark. Among the celebrations with the richest traditions are various kinds of carnivals in connection with Shrovetide. On the Faroe Islands, children dress up in festive costumes and wear imaginative masks, after which they visit friends and family who typically give them treats or loose change. A kind of game, it is called to "walk like bogeymen" ("gå som grýla" in Faroese). This creature is otherwise known from folk beliefs to wander around ensuring that no children eat meat during the fast. A presumably ancient rhyme about this creature has survived. It carries a sack, into which it puts the children who have been so reckless as to breach the strict directive about fasting between Shrovetide and Easter, which we know from Catholic countries, for example.

A legend speaks of the filthy rich Gæsa, who owned half of the island Streymoy but was caught eating meat during the fast, for which he was sentenced to relinquish all of his earthly possessions.

This Catholic custom – both the carnival and probably also the fast – is widespread. The Rio Carnival is famous and has evolved into a huge tourist magnet. In most of the Southern European countries, Shrovetide is also celebrated with big carnivals and somewhat wild shenanigans.

An unavoidable consequence of our time is the commercialisation of popular customs. A significant amount of money is spent and made in connection with carnivals, and not least the media is eager to televise the colourful and spectacular parades in the streets of Rio and other cities. Another consequence of our time is the Anglo-Saxon influence. These days, the traditional masquerade at Shrovetide is being replaced by the Anglo-American Halloween, which originated as a Gaelic festival of light among carnival-like masquerades. It is interesting to note how this custom has gained ground in our Nordic culture without people giving much thought to the fact that similar celebratory customs have existed in our culture since the dawn of time. Perhaps it is also due to late autumn being a time for festivities and fun. Halloween is celebrated on 1 November , after all, while Shrovetide takes place in the spring and has to compete with the onset of the many summer activities.

The mare

The mare appears at night and sits or lies on sleeping people, disturbing their sleep, causing evil dreams, and suppressing their breathing. It often appears in the guise of a beautiful woman – but is in fact an abominable monster. It wants to stick its fingers into the sleeper’s mouth in order to count the teeth. If it succeeds, the sleeping individual will die.

Most people sleep badly from time to time and may experience chest tightness, be unable to exhale freely and have nightmares at night. There are many possible causes of disturbed sleep without sufficient rest: illness and worries are often the cause of disturbed sleep in the same way as overeating or eating something wrong can lead to those types of symptoms. Natural causes of these kinds have presumably given rise to the superstitious beliefs surrounding the mare.

We know of many good pieces of advice involving the mare. One could recite certain, often ritualistic verses or rhymes which were considered capable of keeping the mare away. One piece of advice was to wrap a knife in a cloth, or preferably a garter, and then move it around the person who feared the mare by letting it go from one hand to the other while reciting a mare verse. In a few places, it is advised to place one’s shoes in front of the bed with toes pointing outwards, as this will prevent the mare from getting into the bed.

The belief in a mare or similar creature features in all cultures, supposedly because disturbed sleep is a universal human phenomenon. In many places, people believed that some individuals were capable of transforming themselves into a mare in order to hurt their enemies. Mare stories with obvious sexual connotations also occur. These usually involve a mare in the guise of a woman who seeks out sleeping men, and, conversely, a male form who looks for sleeping women.

The belief in a mare has been strong in many cultures. The oldest Nordic Christian laws include fines for people who take on the form of a mare and seek out others in their homes.

The mare often appears in the form of a woman flying through the air. We therefore sometimes see a correlation with superstitious beliefs about witches. Indeed, it is believed that women flew to Bloksbjerg on broomsticks in order to indulge in wild excesses together with Satan. There is no original connection between these two popular beliefs.

Scarcely anyone living in our part of the world today believes in the mare, and yet we have preserved it in our language. We talk of having nightmares following a night of unsettling dreams and we refer to a problem that has proven to be difficult to solve as a mare .

The murdered child as a ghost

A common notion in folk beliefs is that when certain people die they are transformed into one animal form or another and can appear as ghosts. On the Faroe Islands and in many other places, there is thus the belief that children concealed at birth and murdered come back to haunt and show themselves to the living in one form or another. If we are to believe the Faroese belief, this ghost is small and chubby, bears a likeness to a child, and is no larger than a ball of yarn. The most common explanation for why they come back to haunt is that they want to have a name because they died without being christened.

A name is meaningful and to not have a name is an unhappy state of being. When a newborn baby is christened and given a name, it is also given its own place in the family and in society. It becomes a person. The name stays with that individual throughout his or her life and is entered into official registers, even after death, as proof that this person really did live. The little child murdered at birth is never given a place in life; it is not registered and no one ever becomes aware of its existence. It is unwanted and silently pushed away.

Should the unhappy child succeed in getting a name, its apparition will also disappear, never to be seen again. In Faroeses, this ghost is called a “niðagrísur”, which refers in part to it not having achieved a blessed life (niða means in the opposite direction of the blessed life) and in part to an animalistic form (grísur means pig) because it never became a person. Some researchers believe that this ghost originates from the time before Christ, specifically because what matters is the name and not the ritual of a church christening as a sacrament.

Near the village of Skála on the Faroe Islands, there is a boulder called Loddasasteinur (Lodda’s Boulder) . It was often possible to meet the ghost of a murdered child here. A man from the village once became so irritated when he came upon it that he shouted: “What a loddas!” No one has ever seen the ghost since. It was believed that it perceived the expression to be its name and thus found peace. (Incidentally, the meaning of the word ‘loddas’ is unclear.)

In the village of Virðareiði , a housemaid gave birth to a child in secret. She wrapped it in leg warmers and buried it. When the girl later married, the child turned up at the wedding as a ghost in the leg warmers, where it rolled around between the legs of the guests and sang a song about its cruel fate.

The beach troll

In the old days, people believed in trolls. They lived beyond the human domain in poorly accessible and impassable areas high up on the fells or deep in the mountains. The world of trolls was dark and scary and they belonged to the heathen world. They were dangerous and menacing.

There were many stories and legends about trolls, although opinions differ as to whether people genuinely believed in their existence. Many researchers believe that stories about dangerous trolls served a pedagogic purpose primarily and were intended to make children, and perhaps also a few adults, afraid of seeking out perilous places – especially in the dark.

A famous legend tells the story of a troll, who, at dusk one evening succeeded in abducting one of the children from the village of Hattarvík on Fugloy. An old man leapt after the troll and managed to save the child from the edge of the cliff down by the sea. The troll jumped into the sea and thus became known as a beach troll. The same village is the centre of another story about a beach troll, who could often be witnessed coming onto land at dusk. The troll is said to have been terrifying. Seaweed grew and pebbles hung all over its body. When it moved it sounded as if it was dragging millstones behind it and the ground came loose and spun around it. It was so large that it could be seen above the tallest houses. A man eventually succeeded in exorcising it, and no one has seen or heard from it since.

In the village of Hattarvík, the cliff facing the sea is quite steep in places, the beach below is narrow, and the surf is often rough. One can therefore easily imagine the adults worrying about their children and envisage them having reasons for scaring them into staying away from the dangers lurking down by the beach.

Eyðun Andreasen, Professor

The conceptions about the ”Niðagrísur” (The Child Ghost) derive from a serious crime. The fact that the ”Grýla” (The Monster) goes for the children, derives from the need to observe ecclesiastical orders. The Beach Trolls keep the children away from the beach and thereby great danger – and the conceptions about the Mare is a symtom of physical and mental stress, which most people experience during their lifetime.

The bogeyman – scary disguise

Celebrations involving dressing up in various disguises are a feature of cultures throughout the world, including Denmark. Among the celebrations with the richest traditions are various kinds of carnivals in connection with Shrovetide. On the Faroe Islands, children dress up in festive costumes and wear imaginative masks, after which they visit friends and family who typically give them treats or loose change. A kind of game, it is called to "walk like bogeymen" ("gå som grýla" in Faroese). This creature is otherwise known from folk beliefs to wander around ensuring that no children eat meat during the fast. A presumably ancient rhyme about this creature has survived. It carries a sack, into which it puts the children who have been so reckless as to breach the strict directive about fasting between Shrovetide and Easter, which we know from Catholic countries, for example.

A legend speaks of the filthy rich Gæsa, who owned half of the island Streymoy but was caught eating meat during the fast, for which he was sentenced to relinquish all of his earthly possessions.

This Catholic custom – both the carnival and probably also the fast – is widespread. The Rio Carnival is famous and has evolved into a huge tourist magnet. In most of the Southern European countries, Shrovetide is also celebrated with big carnivals and somewhat wild shenanigans.

An unavoidable consequence of our time is the commercialisation of popular customs. A significant amount of money is spent and made in connection with carnivals, and not least the media is eager to televise the colourful and spectacular parades in the streets of Rio and other cities. Another consequence of our time is the Anglo-Saxon influence. These days, the traditional masquerade at Shrovetide is being replaced by the Anglo-American Halloween, which originated as a Gaelic festival of light among carnival-like masquerades. It is interesting to note how this custom has gained ground in our Nordic culture without people giving much thought to the fact that similar celebratory customs have existed in our culture since the dawn of time. Perhaps it is also due to late autumn being a time for festivities and fun. Halloween is celebrated on 1 November , after all, while Shrovetide takes place in the spring and has to compete with the onset of the many summer activities.

The mare

The mare appears at night and sits or lies on sleeping people, disturbing their sleep, causing evil dreams, and suppressing their breathing. It often appears in the guise of a beautiful woman – but is in fact an abominable monster. It wants to stick its fingers into the sleeper’s mouth in order to count the teeth. If it succeeds, the sleeping individual will die.

Most people sleep badly from time to time and may experience chest tightness, be unable to exhale freely and have nightmares at night. There are many possible causes of disturbed sleep without sufficient rest: illness and worries are often the cause of disturbed sleep in the same way as overeating or eating something wrong can lead to those types of symptoms. Natural causes of these kinds have presumably given rise to the superstitious beliefs surrounding the mare.

We know of many good pieces of advice involving the mare. One could recite certain, often ritualistic verses or rhymes which were considered capable of keeping the mare away. One piece of advice was to wrap a knife in a cloth, or preferably a garter, and then move it around the person who feared the mare by letting it go from one hand to the other while reciting a mare verse. In a few places, it is advised to place one’s shoes in front of the bed with toes pointing outwards, as this will prevent the mare from getting into the bed.

The belief in a mare or similar creature features in all cultures, supposedly because disturbed sleep is a universal human phenomenon. In many places, people believed that some individuals were capable of transforming themselves into a mare in order to hurt their enemies. Mare stories with obvious sexual connotations also occur. These usually involve a mare in the guise of a woman who seeks out sleeping men, and, conversely, a male form who looks for sleeping women.

The belief in a mare has been strong in many cultures. The oldest Nordic Christian laws include fines for people who take on the form of a mare and seek out others in their homes.

The mare often appears in the form of a woman flying through the air. We therefore sometimes see a correlation with superstitious beliefs about witches. Indeed, it is believed that women flew to Bloksbjerg on broomsticks in order to indulge in wild excesses together with Satan. There is no original connection between these two popular beliefs.

Scarcely anyone living in our part of the world today believes in the mare, and yet we have preserved it in our language. We talk of having nightmares following a night of unsettling dreams and we refer to a problem that has proven to be difficult to solve as a mare .

The murdered child as a ghost

A common notion in folk beliefs is that when certain people die they are transformed into one animal form or another and can appear as ghosts. On the Faroe Islands and in many other places, there is thus the belief that children concealed at birth and murdered come back to haunt and show themselves to the living in one form or another. If we are to believe the Faroese belief, this ghost is small and chubby, bears a likeness to a child, and is no larger than a ball of yarn. The most common explanation for why they come back to haunt is that they want to have a name because they died without being christened.

A name is meaningful and to not have a name is an unhappy state of being. When a newborn baby is christened and given a name, it is also given its own place in the family and in society. It becomes a person. The name stays with that individual throughout his or her life and is entered into official registers, even after death, as proof that this person really did live. The little child murdered at birth is never given a place in life; it is not registered and no one ever becomes aware of its existence. It is unwanted and silently pushed away.

Should the unhappy child succeed in getting a name, its apparition will also disappear, never to be seen again. In Faroeses, this ghost is called a “niðagrísur”, which refers in part to it not having achieved a blessed life (niða means in the opposite direction of the blessed life) and in part to an animalistic form (grísur means pig) because it never became a person. Some researchers believe that this ghost originates from the time before Christ, specifically because what matters is the name and not the ritual of a church christening as a sacrament.

Near the village of Skála on the Faroe Islands, there is a boulder called Loddasasteinur (Lodda’s Boulder) . It was often possible to meet the ghost of a murdered child here. A man from the village once became so irritated when he came upon it that he shouted: “What a loddas!” No one has ever seen the ghost since. It was believed that it perceived the expression to be its name and thus found peace. (Incidentally, the meaning of the word ‘loddas’ is unclear.)

In the village of Virðareiði , a housemaid gave birth to a child in secret. She wrapped it in leg warmers and buried it. When the girl later married, the child turned up at the wedding as a ghost in the leg warmers, where it rolled around between the legs of the guests and sang a song about its cruel fate.

The beach troll

In the old days, people believed in trolls. They lived beyond the human domain in poorly accessible and impassable areas high up on the fells or deep in the mountains. The world of trolls was dark and scary and they belonged to the heathen world. They were dangerous and menacing.

There were many stories and legends about trolls, although opinions differ as to whether people genuinely believed in their existence. Many researchers believe that stories about dangerous trolls served a pedagogic purpose primarily and were intended to make children, and perhaps also a few adults, afraid of seeking out perilous places – especially in the dark.

A famous legend tells the story of a troll, who, at dusk one evening succeeded in abducting one of the children from the village of Hattarvík on Fugloy. An old man leapt after the troll and managed to save the child from the edge of the cliff down by the sea. The troll jumped into the sea and thus became known as a beach troll. The same village is the centre of another story about a beach troll, who could often be witnessed coming onto land at dusk. The troll is said to have been terrifying. Seaweed grew and pebbles hung all over its body. When it moved it sounded as if it was dragging millstones behind it and the ground came loose and spun around it. It was so large that it could be seen above the tallest houses. A man eventually succeeded in exorcising it, and no one has seen or heard from it since.

In the village of Hattarvík, the cliff facing the sea is quite steep in places, the beach below is narrow, and the surf is often rough. One can therefore easily imagine the adults worrying about their children and envisage them having reasons for scaring them into staying away from the dangers lurking down by the beach.

Eyðun Andreasen, Professor

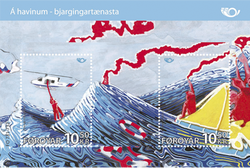

Rescue at Sea

Date Of Issue 21.03.2012

Nordic Issue

Date Of Issue 21.03.2012

Nordic Issue

It is widely accepted that the most dangerous of all workplaces is the sea.

Naturally, the effects of this fact are primarily felt by the countries most dependent on the sea, such as the Faroe Islands.

The biggest known accident at sea in the Faroe Islands occurred around the year 1600. A storm suddenly appeared from the northeast and 50 boats never returned home. It is believed that 200 to 300 fishermen were killed in the storm. Because the majority of the boats that did not return home were small, the use of small boats was then prohibited. Thus, this major accident resulted in the first known initiative to make the sea a safer workplace.

But there were still many maritime accidents that claimed the lives of many victims. There are no precise figures, but the victims were in the thousands, making a significant impact on a community as small as the Faroe Islands.

The lives of many fishermen were lost in the first half of the previous century. On more than one occasion, many crews of up to 23 men each disappeared at the same time.

There are also reports from this period of incredible rescue efforts. For example, in 1930 during a snowstorm, the schooner “Ernestine” crashed into a reef off the southern coast of Iceland. A member of the crew, Ziska Jacobsen, swam in the worst imaginable conditions to the shore with a line, enabling the rescue of 17 of the 26 crew members.

It would take another accident before an initiative was taken to establish an actual rescue service in the Faroe Islands. In 1957, the Icelandic trawler “Goðanes” crashed into a reef at the approach to Skálafjørð on the island of Eysturoy. Although there was a willingness to rescue the crew, the Faroe Islands were simply not equipped to handle such a situation. The captain of “Goðanes” died in the accident. Following this accident, the Icelandic rescue company, Slýsavarnafelag Íslands, donated equipment to the Faroese for rescuing crews from ships in distress, sparking the establishment of rescue associations around the Faroe Islands. These rescue associations have been very well equipped. And they have made great efforts when there has been a need for them.

It took some time before the Faroe Islands established a formal rescue service. This happened in 1976, in connection with the founding of the Fisheries Inspectorate. In addition to fisheries inspection, the inspectorate was also charged with the task of participating in search and rescue efforts at sea in cooperation with the MRCC, Maritime Rescue Coordination Center. The Fisheries Inspectorate also had a cooperation agreement with the large Faroese insurance company. This primarily involved towage and diving assistance. The Fisheries Inspectorate and Ships Inspectorate also cooperate on monitoring the conditions for crews on board ships. The Fisheries Inspectorate examines the crew documents, while the ships are fishing. It has the power to order ships into port if it finds violations of crewing and inspection regulations. The MRCC also cooperates to operate Tórshavn Radio, both agencies under the Ministry of Fisheries.

MRCC Tórshavn is responsible for initiating and coordinating search and rescue efforts in Faroese waters. Cooperation agreements have been established with various partners, including: Atlantic Helicopters, Island Command Faroes, the Fisheries Inspectorate and our neighbouring countries regarding assistance in emergencies.

MRCC Tórshavn also has the task of receiving notification of oil spills in Faroese waters, organising patient transports by helicopter, forwarding notifications of terrorist threats against Faroese ships (ISPS) and to formulate and announce marine warnings.

The MRCC’s area of operation is out to 200 nautical miles from land, or to the midline between our neighbouring countries. The station is staffed around the clock throughout the year.

For added security, it is required by law that anyone who goes to sea must have taken a safety course, so that crews are well prepared in case of an emergency situation. In addition, ships today are much better equipped for safety, making life at sea much safer today than in the past.

Therefore, work at sea can now be considered a safe occupation. Deaths at sea are now rare, although absolute safety can never be achieved. But when something does happen, everything that can possibly be done to save human lives is done.

It should be added that the Danish fisheries inspection is also part of this history. It has operated in Faroese waters since the beginning of the 20th century and has always been ready to assist when asked for help. The fisheries inspection became especially useful to the Faroese in the 1960s when it was equipped with a helicopter, which has carried out many search and rescue operations.

Óli Jacobsen

Naturally, the effects of this fact are primarily felt by the countries most dependent on the sea, such as the Faroe Islands.

The biggest known accident at sea in the Faroe Islands occurred around the year 1600. A storm suddenly appeared from the northeast and 50 boats never returned home. It is believed that 200 to 300 fishermen were killed in the storm. Because the majority of the boats that did not return home were small, the use of small boats was then prohibited. Thus, this major accident resulted in the first known initiative to make the sea a safer workplace.

But there were still many maritime accidents that claimed the lives of many victims. There are no precise figures, but the victims were in the thousands, making a significant impact on a community as small as the Faroe Islands.

The lives of many fishermen were lost in the first half of the previous century. On more than one occasion, many crews of up to 23 men each disappeared at the same time.

There are also reports from this period of incredible rescue efforts. For example, in 1930 during a snowstorm, the schooner “Ernestine” crashed into a reef off the southern coast of Iceland. A member of the crew, Ziska Jacobsen, swam in the worst imaginable conditions to the shore with a line, enabling the rescue of 17 of the 26 crew members.

It would take another accident before an initiative was taken to establish an actual rescue service in the Faroe Islands. In 1957, the Icelandic trawler “Goðanes” crashed into a reef at the approach to Skálafjørð on the island of Eysturoy. Although there was a willingness to rescue the crew, the Faroe Islands were simply not equipped to handle such a situation. The captain of “Goðanes” died in the accident. Following this accident, the Icelandic rescue company, Slýsavarnafelag Íslands, donated equipment to the Faroese for rescuing crews from ships in distress, sparking the establishment of rescue associations around the Faroe Islands. These rescue associations have been very well equipped. And they have made great efforts when there has been a need for them.

It took some time before the Faroe Islands established a formal rescue service. This happened in 1976, in connection with the founding of the Fisheries Inspectorate. In addition to fisheries inspection, the inspectorate was also charged with the task of participating in search and rescue efforts at sea in cooperation with the MRCC, Maritime Rescue Coordination Center. The Fisheries Inspectorate also had a cooperation agreement with the large Faroese insurance company. This primarily involved towage and diving assistance. The Fisheries Inspectorate and Ships Inspectorate also cooperate on monitoring the conditions for crews on board ships. The Fisheries Inspectorate examines the crew documents, while the ships are fishing. It has the power to order ships into port if it finds violations of crewing and inspection regulations. The MRCC also cooperates to operate Tórshavn Radio, both agencies under the Ministry of Fisheries.

MRCC Tórshavn is responsible for initiating and coordinating search and rescue efforts in Faroese waters. Cooperation agreements have been established with various partners, including: Atlantic Helicopters, Island Command Faroes, the Fisheries Inspectorate and our neighbouring countries regarding assistance in emergencies.

MRCC Tórshavn also has the task of receiving notification of oil spills in Faroese waters, organising patient transports by helicopter, forwarding notifications of terrorist threats against Faroese ships (ISPS) and to formulate and announce marine warnings.

The MRCC’s area of operation is out to 200 nautical miles from land, or to the midline between our neighbouring countries. The station is staffed around the clock throughout the year.

For added security, it is required by law that anyone who goes to sea must have taken a safety course, so that crews are well prepared in case of an emergency situation. In addition, ships today are much better equipped for safety, making life at sea much safer today than in the past.

Therefore, work at sea can now be considered a safe occupation. Deaths at sea are now rare, although absolute safety can never be achieved. But when something does happen, everything that can possibly be done to save human lives is done.

It should be added that the Danish fisheries inspection is also part of this history. It has operated in Faroese waters since the beginning of the 20th century and has always been ready to assist when asked for help. The fisheries inspection became especially useful to the Faroese in the 1960s when it was equipped with a helicopter, which has carried out many search and rescue operations.

Óli Jacobsen

All Issues Copyright Posta, www.stamps.fo