2016

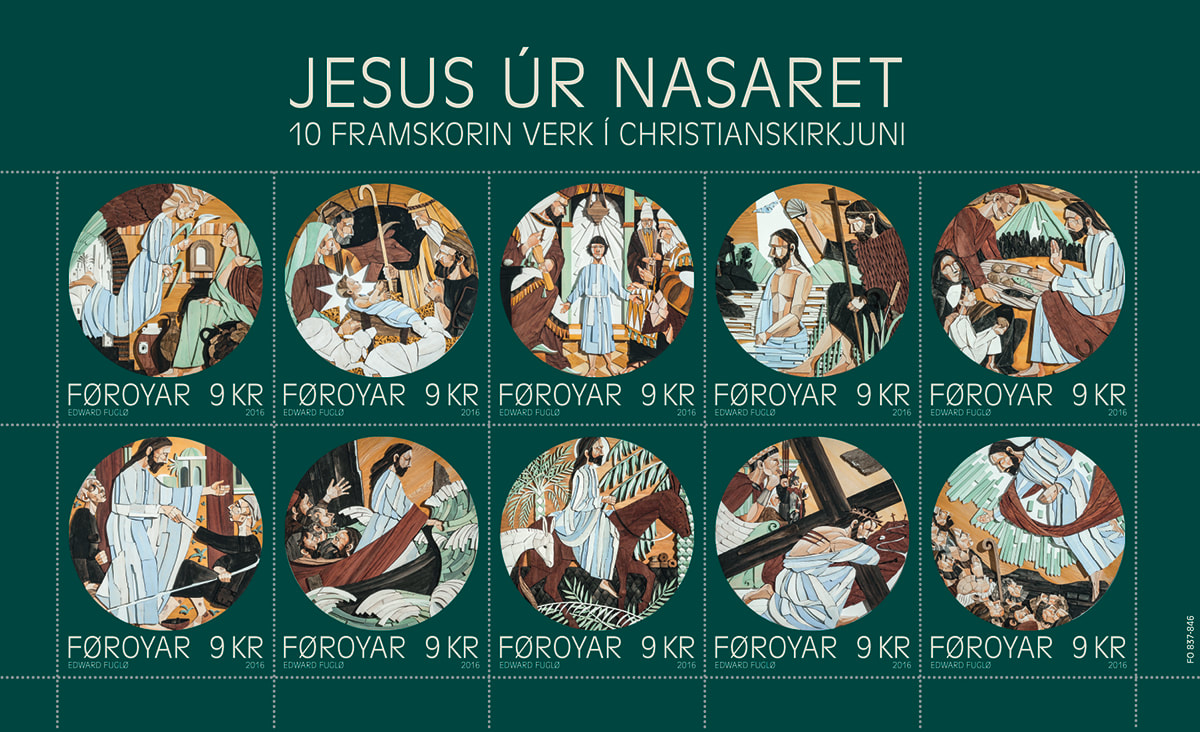

The Message of the Wood

Date Of Issue 26.09.2016

Date Of Issue 26.09.2016

The Message of the Wood

On Edward Fuglø's Decoration in The Christian's Church

In the Spring of 2013, Edward Fuglø created ten, mixed-media wood and acrylic ornamental reliefs for Christianskirkjan, Christian’s Church, in Klaksvík, Faroe Islands. The reliefs depict scenes from the life of Jesus. The medium wood is quite appropriate when we think of the Saviour as the foster son of Joseph, the carpenter.

Another reason for the use of wood as the medium is its frequent use in the Church, where the mighty wooden structure of the nave is reminiscent of the great halls of the Viking Era. The round shields mounted alongside Viking ships have also influenced Edward Fuglø's choice of a circular shape for his reliefs.

Unlike painted pictures, the reliefs surge forward in space, creating deep shadows. They serve as decoration of a wide meeting room with a low ceiling situated below the sanctuary of the Church. Thus, the powerful effect of the reliefs as a collective whole can also be seen as a response to this demanding environment.

The circular form is an old symbol of the eternal, which makes it particularly appropriate in a religious narrative. However, it also poses an artistic challenge: The images must adapt to the circular form, while resisting it at the same time. Edward Fuglø has resolved this dilemma in a masterly fashion. Some of his figures bow humbly beneath the curved frame, whereas others rise against it, as if it did not exist.

The storytelling is brief and dramatic, revolving around the calm and dignified persona of Christ Jesus. Like the eye of a hurricane, He is surrounded by a violent cascade of movement and the expectant and lively faces of His disciples and the crowds of His followers, which are a masterwork of expressionism.

In the spirit of Pop Art, Edward Fuglø does not shy away from banalities. The style is "biblical": simple, clear and direct. This particular Biblical treatment has had a long and checkered history, but at one time it was revolutionary and powerful, especially in the Italian Renaissance art of Giotto and his followers. Their art also inspired Joakim Frederik Skovgaard's altarpiece in Christianskirkjan, a fresco of The Great Feast (1901), to which Fuglø's reliefs therfore connect.

The reliefs are not only retro. They are reminiscent of three-dimensional maps with contour lines. The displacements are so extensive that the whole assumes a dissolved, cubist look when the work is seen at close quarters or from the side. Simplicity and complexity go hand-in-hand, and the story is enriched by the decoration of the abstract pieces, often in robust rhythms.

Amidst the wood and acrylic reliefs, strange foreign elements appear, such as a light switch, a fish hook, a lock, a rivet, all of which endow the reliefs with a touch of collage. These are items that people have given the artist. As objects with special meaning for the donators, Edward Fuglø has incorporated them into his work as a local commentary on a sacred history. Thus, the life and passion of Jesus becomes uniquely present and personal.

The order of the narrative is also interesting. For example, the relief of Jesus Calms the Storm appears later than it should and so provides additional drama to the Passion of Christ. Likewise, The Ascension also reflects His Return on Judgement Day.

A wealth of thought-provoking details meets the eye. In Jesus Enters Jerusalem, Jesus rides alone without the traditional jubilant crowd; he meets his fate alone. In The Baptism of Christ, a tiny deer appears in the background, an allusion to the words of David, Psalm 42: “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God”. As Christian art of old, the reliefs offer both good storytelling and satisfying nourishment for the mind and soul.

The reliefs were developed in close co-operation with Sjúrður Sólstein, a cabinetmaker and instructor at Klaksvík Technical School, which provided the workspace for the crafting of the individual reliefs. Sólstein was responsible for the difficult and demanding work of carving the numerous components of the individual reliefs, following Edward Fuglø's detailed, 1:1 ratio designs.

With their magical mix of simplicity and complexity, narrative and decoration, old and new, imagination and handicraft, Edward Fuglø's reliefs constitute a brilliant contribution to Faroese church art. The Carpenter of Nazareth would have nodded in appreciation.

And to conclude, some facts:

Each relief consists of a 2 cm thick birch plate with a diameter of 135 cm, edged by 2 cm of brass, which originally was the brass baseboards of earlier, now replaced, pews of the Church.

Varnished, painted (acrylic) or unfinished wooden pieces have been glued onto the base plate. The materials are spruce, African bubinga and zebrawood, and, not least, pine, which comes mainly from the former stretcher of the Church's altarpiece. To this is added driftwood, used metal parts, etc.

The motifs - clockwise from left - are as follows:

1. The Annunciation (Luke 1: 26-38)

2. The Adoration of the Shepherds (Luke 2: 8-21)

3. Jesus at the Age of Twelve in the Temple (Luke 2: 41-52)

4. The Baptism of Christ (Matthew 3: 13-17, Mark 1: 9-11, Luke 3: 21-22, John 1: 29-34)

5. Jesus Feeds the Multitude of Five Thousand (Matthew 14: 13-21, Mark 6: 30-44, Luke 9: 10-17, John 6: 1-15)

6. The Healing of the Ten Lepers (Luke 17: 11-19)

7. Jesus Calms the Storm (Matthew 8: 23-27, Mark 4: 35-41, Luke 8: 22-25)

8. Jesus Enters Jerusalem (Matthew 21: 1-11, Mark 1: 1-11, Luke 19: 28-40 John (12: 12-19)

9. Jesus Carries His Cross (Matthew 27:32, Mark, 15:21, Luke 23: 26-32, John 19:17)

10. The Ascension (Luke 24: 50-53, Acts 1: 9-12)

Accompanying the ornamentation are also six, small vignettes, which are mounted between the windows of the Church. They consist of carved and painted shapes that function as close-ups of details from the reliefs themselves: a star, a lamb, a column, a fish, a jug and a dove.

On Edward Fuglø's Decoration in The Christian's Church

In the Spring of 2013, Edward Fuglø created ten, mixed-media wood and acrylic ornamental reliefs for Christianskirkjan, Christian’s Church, in Klaksvík, Faroe Islands. The reliefs depict scenes from the life of Jesus. The medium wood is quite appropriate when we think of the Saviour as the foster son of Joseph, the carpenter.

Another reason for the use of wood as the medium is its frequent use in the Church, where the mighty wooden structure of the nave is reminiscent of the great halls of the Viking Era. The round shields mounted alongside Viking ships have also influenced Edward Fuglø's choice of a circular shape for his reliefs.

Unlike painted pictures, the reliefs surge forward in space, creating deep shadows. They serve as decoration of a wide meeting room with a low ceiling situated below the sanctuary of the Church. Thus, the powerful effect of the reliefs as a collective whole can also be seen as a response to this demanding environment.

The circular form is an old symbol of the eternal, which makes it particularly appropriate in a religious narrative. However, it also poses an artistic challenge: The images must adapt to the circular form, while resisting it at the same time. Edward Fuglø has resolved this dilemma in a masterly fashion. Some of his figures bow humbly beneath the curved frame, whereas others rise against it, as if it did not exist.

The storytelling is brief and dramatic, revolving around the calm and dignified persona of Christ Jesus. Like the eye of a hurricane, He is surrounded by a violent cascade of movement and the expectant and lively faces of His disciples and the crowds of His followers, which are a masterwork of expressionism.

In the spirit of Pop Art, Edward Fuglø does not shy away from banalities. The style is "biblical": simple, clear and direct. This particular Biblical treatment has had a long and checkered history, but at one time it was revolutionary and powerful, especially in the Italian Renaissance art of Giotto and his followers. Their art also inspired Joakim Frederik Skovgaard's altarpiece in Christianskirkjan, a fresco of The Great Feast (1901), to which Fuglø's reliefs therfore connect.

The reliefs are not only retro. They are reminiscent of three-dimensional maps with contour lines. The displacements are so extensive that the whole assumes a dissolved, cubist look when the work is seen at close quarters or from the side. Simplicity and complexity go hand-in-hand, and the story is enriched by the decoration of the abstract pieces, often in robust rhythms.

Amidst the wood and acrylic reliefs, strange foreign elements appear, such as a light switch, a fish hook, a lock, a rivet, all of which endow the reliefs with a touch of collage. These are items that people have given the artist. As objects with special meaning for the donators, Edward Fuglø has incorporated them into his work as a local commentary on a sacred history. Thus, the life and passion of Jesus becomes uniquely present and personal.

The order of the narrative is also interesting. For example, the relief of Jesus Calms the Storm appears later than it should and so provides additional drama to the Passion of Christ. Likewise, The Ascension also reflects His Return on Judgement Day.

A wealth of thought-provoking details meets the eye. In Jesus Enters Jerusalem, Jesus rides alone without the traditional jubilant crowd; he meets his fate alone. In The Baptism of Christ, a tiny deer appears in the background, an allusion to the words of David, Psalm 42: “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God”. As Christian art of old, the reliefs offer both good storytelling and satisfying nourishment for the mind and soul.

The reliefs were developed in close co-operation with Sjúrður Sólstein, a cabinetmaker and instructor at Klaksvík Technical School, which provided the workspace for the crafting of the individual reliefs. Sólstein was responsible for the difficult and demanding work of carving the numerous components of the individual reliefs, following Edward Fuglø's detailed, 1:1 ratio designs.

With their magical mix of simplicity and complexity, narrative and decoration, old and new, imagination and handicraft, Edward Fuglø's reliefs constitute a brilliant contribution to Faroese church art. The Carpenter of Nazareth would have nodded in appreciation.

And to conclude, some facts:

Each relief consists of a 2 cm thick birch plate with a diameter of 135 cm, edged by 2 cm of brass, which originally was the brass baseboards of earlier, now replaced, pews of the Church.

Varnished, painted (acrylic) or unfinished wooden pieces have been glued onto the base plate. The materials are spruce, African bubinga and zebrawood, and, not least, pine, which comes mainly from the former stretcher of the Church's altarpiece. To this is added driftwood, used metal parts, etc.

The motifs - clockwise from left - are as follows:

1. The Annunciation (Luke 1: 26-38)

2. The Adoration of the Shepherds (Luke 2: 8-21)

3. Jesus at the Age of Twelve in the Temple (Luke 2: 41-52)

4. The Baptism of Christ (Matthew 3: 13-17, Mark 1: 9-11, Luke 3: 21-22, John 1: 29-34)

5. Jesus Feeds the Multitude of Five Thousand (Matthew 14: 13-21, Mark 6: 30-44, Luke 9: 10-17, John 6: 1-15)

6. The Healing of the Ten Lepers (Luke 17: 11-19)

7. Jesus Calms the Storm (Matthew 8: 23-27, Mark 4: 35-41, Luke 8: 22-25)

8. Jesus Enters Jerusalem (Matthew 21: 1-11, Mark 1: 1-11, Luke 19: 28-40 John (12: 12-19)

9. Jesus Carries His Cross (Matthew 27:32, Mark, 15:21, Luke 23: 26-32, John 19:17)

10. The Ascension (Luke 24: 50-53, Acts 1: 9-12)

Accompanying the ornamentation are also six, small vignettes, which are mounted between the windows of the Church. They consist of carved and painted shapes that function as close-ups of details from the reliefs themselves: a star, a lamb, a column, a fish, a jug and a dove.

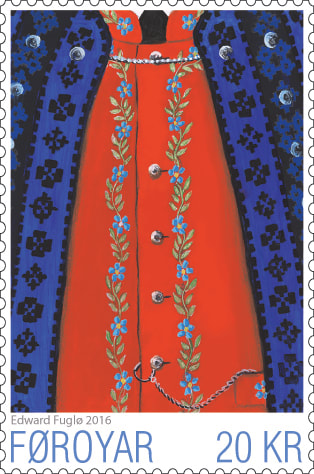

The Faroese National Costume I

Date Of Issue 26.09.2016

Date Of Issue 26.09.2016

The Faroese National Costume I

Visitors to the Faroe Islands have hardly failed to notice that many Faroese wear national costumes at parties and town festivals. They will see men wearing breeches and the distinct Faroese hats and women in full-length skirts with beautifully embroidered aprons and shawls, with elegantly made silver jewellery.

In actuality, the Faroese national costume tradition is not very old. The costumes are based on the way everyday clothing looked up until the mid-19th century, and it was only during the national revival in the late 18th century that they started becoming different from the commoner's clothing. The term "føroysk klæðir" (Faroese attire) should be compared to the concept "donsk klæðir" (Danish attire), which designated clothes bought in shops - and does not necessarily denote formal wear. Gradually, as it became more customary to dress in "shop's clothing" as most Europeans did, the traditional attire came to occupy a class by itself. In my childhood we still could see men, especially of the older generation, using breeches, knitted sweaters and hats in everyday life.

Over time, and especially during the national romantic revival in the late 18th century, the Faroese attire began assuming its current status for festive occasions. There have been a number of changes made from the original attire and a certain standardization of both female and male dresses has taken place, so that one can now talk about a genuine national costume. After World War II the use of the national costume gradually increased, but in the last two or three decades it has come back with a vengeance, partly because of nationalism flourishing due to the severe financial crisis in the Faroe Islands in the nineties.

In three annual stamp issues we will illustrate aspects of both the female and male costumes.

Torso - the female costume

The knitted blouse that goes with the female costume is short and tight. It is open in front and has a wide neckline. Traditionally the blouse is red with tiny black patterns or, more rarely, blue with dark blue patterns. Recently, designers have started experimenting with colours - violet, green or yellow, to name just a few.

A detachable bosom is worn underneath the open front of the blouse. The bosom originates in the old festive apparel called "stakkur" and was not being commonly used for this costume in the past. In days of old the bosom was woven or knitted in wool, then fulled or felted, while nowadays being made of lined velvet or similar fabric. The bosom serves two functions - the first as a compensation, let's say if the woman gets a little bigger, enabling her to use the same blouse. Its second function is to serve as an underlay, enhancing the costume's silver ornament.

In order to tighten the blouse against the body, use is made of a silver chain, a so-called "stimi". The stimi is pulled through the eyelets, "malja" in Faroese, on both sides of the blouse opening. A silver needle called "sproti" is at the end of the stimi which is fastened to the blouse after insertion. A source reports that formerly the stimi went up under the bust in order to accentuate it - but now it goes up on the bust of the dress.

Around the waist women wear a wide black belt with ornamented silver buckles. In rare cases, the entire belt is composed of ornamented silver pieces.

A large ornamented silver brooch is on top of the detachable bosom, used to hold the shawl in place. The brooch and belt buckles should preferably match with each other.

On the whole, silver ornamentation plays an important role in the national costume. There are women who, while their daughters are still young, start collecting the single silver pieces which at some point in the future will become a complete set. The silver ornamentation is also often passed on from mother to daughter. The design of the brooch and the silver buckles varies. In recent years Faroese decorative motifs have become more frequent.

Torso - the male costume

Men dressing in the national costume generally wear a white shirt next to the body. Over the shirt they wear a waistcoat with six silver buttons, two small pockets and intricate floral embroideries. The waistcoat is either red or black in front. There is also a white waistcoat variant used by bridegrooms at weddings.

Over the waistcoat men wear a buttoned knitted sweater, open in front with silver buttons on both sides. The sweater is mostly worn open in front, held together at the top by a short silver chain with silver buttons at each end. The buttoned sweater is either uni-coloured dark blue and made of knitted and felted wool - or, as shown on the stamp, light blue with a dark blue pattern.

Visitors to the Faroe Islands have hardly failed to notice that many Faroese wear national costumes at parties and town festivals. They will see men wearing breeches and the distinct Faroese hats and women in full-length skirts with beautifully embroidered aprons and shawls, with elegantly made silver jewellery.

In actuality, the Faroese national costume tradition is not very old. The costumes are based on the way everyday clothing looked up until the mid-19th century, and it was only during the national revival in the late 18th century that they started becoming different from the commoner's clothing. The term "føroysk klæðir" (Faroese attire) should be compared to the concept "donsk klæðir" (Danish attire), which designated clothes bought in shops - and does not necessarily denote formal wear. Gradually, as it became more customary to dress in "shop's clothing" as most Europeans did, the traditional attire came to occupy a class by itself. In my childhood we still could see men, especially of the older generation, using breeches, knitted sweaters and hats in everyday life.

Over time, and especially during the national romantic revival in the late 18th century, the Faroese attire began assuming its current status for festive occasions. There have been a number of changes made from the original attire and a certain standardization of both female and male dresses has taken place, so that one can now talk about a genuine national costume. After World War II the use of the national costume gradually increased, but in the last two or three decades it has come back with a vengeance, partly because of nationalism flourishing due to the severe financial crisis in the Faroe Islands in the nineties.

In three annual stamp issues we will illustrate aspects of both the female and male costumes.

Torso - the female costume

The knitted blouse that goes with the female costume is short and tight. It is open in front and has a wide neckline. Traditionally the blouse is red with tiny black patterns or, more rarely, blue with dark blue patterns. Recently, designers have started experimenting with colours - violet, green or yellow, to name just a few.

A detachable bosom is worn underneath the open front of the blouse. The bosom originates in the old festive apparel called "stakkur" and was not being commonly used for this costume in the past. In days of old the bosom was woven or knitted in wool, then fulled or felted, while nowadays being made of lined velvet or similar fabric. The bosom serves two functions - the first as a compensation, let's say if the woman gets a little bigger, enabling her to use the same blouse. Its second function is to serve as an underlay, enhancing the costume's silver ornament.

In order to tighten the blouse against the body, use is made of a silver chain, a so-called "stimi". The stimi is pulled through the eyelets, "malja" in Faroese, on both sides of the blouse opening. A silver needle called "sproti" is at the end of the stimi which is fastened to the blouse after insertion. A source reports that formerly the stimi went up under the bust in order to accentuate it - but now it goes up on the bust of the dress.

Around the waist women wear a wide black belt with ornamented silver buckles. In rare cases, the entire belt is composed of ornamented silver pieces.

A large ornamented silver brooch is on top of the detachable bosom, used to hold the shawl in place. The brooch and belt buckles should preferably match with each other.

On the whole, silver ornamentation plays an important role in the national costume. There are women who, while their daughters are still young, start collecting the single silver pieces which at some point in the future will become a complete set. The silver ornamentation is also often passed on from mother to daughter. The design of the brooch and the silver buckles varies. In recent years Faroese decorative motifs have become more frequent.

Torso - the male costume

Men dressing in the national costume generally wear a white shirt next to the body. Over the shirt they wear a waistcoat with six silver buttons, two small pockets and intricate floral embroideries. The waistcoat is either red or black in front. There is also a white waistcoat variant used by bridegrooms at weddings.

Over the waistcoat men wear a buttoned knitted sweater, open in front with silver buttons on both sides. The sweater is mostly worn open in front, held together at the top by a short silver chain with silver buttons at each end. The buttoned sweater is either uni-coloured dark blue and made of knitted and felted wool - or, as shown on the stamp, light blue with a dark blue pattern.

Europa 2016: Think green

Date Of Issue 09.05.2016

Date Of Issue 09.05.2016

Europa 2016: Think green

Renewable energy is on everyone's mind these days. There are definite limits to the earth's fossil fuel resources. Oil and coal-fired power plants are contributing excessively to the total CO2 emissions, already affecting the global climate to such an extent that we now are able to physically measure the negative consequences. Then there is the unsettling conclusion of Murphy's Law stating that "anything that can go wrong, will go wrong" – something that repeatedly has been confirmed by the otherwise efficient nuclear power plants.

In the Faroe Islands it was the topography of the country, the steep mountain sides and the vast amounts of rain, which from the very beginning spurred the interest in renewable energy.

The pioneer

Already back in 1907, Ólavur á Heygum, a farmer and a businessman, attempted to have a hydroelectric plant built in his hometown of Vestmanna. He had an idea of stemming the precipitous river Fossá, conducting the water down to a turbine located on the shore. Ólavur started a simple damming of the river, but lack of interest and funding meant that the project had to be abandoned. Until his dying day in 1923 Ólavur tried to win support for his plans, but political bickering and personal bankruptcy due to his idealistic undertakings, put an effective end to his pioneering efforts.

In Botn

Instead, it was due to efforts by insightful local businessmen and the municipal council in Vágur in Suðuroy that the first hydroelectric plant in the Faroes was built. By damming up two mountain lakes in the mountains north of the village and conducting the water in pipes down to the turbines at the base of the steep valley "in Botn" on the west coast, an efficient power plant eventually started producing electricity for the entire island. The hydropower plant was commissioned in 1921 and is still operative.

In the same year that the hydroelectric power plant "in Botn" started producing electricity, an engine power plant was commissioned in Torshavn, where topographic conditions for hydroelectric plants are non-existent. In 1931 a hydroelectric power plant started operating "Norðuri á Strond", close to the booming fishing town of Klaksvík on Borðoy island. In the years that followed small and major water and engine power plants began operation in various locations – but it was not until after the Second World War that efforts were made to coordinate an effective production of electric power.

SEV

In 1946 19 municipalities in the centrally located islands of Streymoy, Eysturoy and Vágar, founded a public electric production company named SEV. The company was tasked to coordinate and fund a joint effort in electric power production and in 1951 a large-scale project was initiated with the aim of realizing Ólavur á Heygum's vision of a hydropower plant in Vestmanna. Dams were built in mountain creeks and the water was channelled in pipes down to a power station on the banks of the river Fossá. On May 5th 1954, the Fossá power plant became operative. In a period of nine years following the Fossá project, two more hydroelectric plants were built at Vestmanna.

In 1963 power production capacities across the country were transferred to SEV, power producer and distributor. Consequently SEV assumed control over the local hydro- and engine plants. The distribution network was streamlined and smaller engine power plants around the islands were taken out of service.

Throughout the sixties energy needs in the Faroes increased constantly, especially in the central regions. It was therefore decided to build a power plant operating on crude oil in the Sund region north of Tórshavn. In 1975, two large machines in the Sund power plant became operative. The plant was further expanded in the late seventies and early eighties and now comprises five machines. Functioning mainly as a backup the Sund power plant is capable of supplying the entire Faroe Islands with electric power if, for some reason, the rest of the plants should become inoperative.

The Eiði Hydropower Plant

The Sund power plant turned out to be an expensive affair even before it was finished. The oil crises in the early and late seventies opened the eyes of the decision-makers to the fact that renewable energy was the way forward. A decision was made to further expand hydropower plants - this time exploiting major water resources in a mountain lake called Eiðisvatn, south of the village of Eiði in Eysturoy.

The project called for the construction of a power plant and dam to increase the capacity of Eiðisvatn. In addition, tunnels were drilled in several phases to rivers in the area. The first turbine in the Eiði power plant became operative in 1987, and in 2014 the power plant was finally finished with the installation of three powerful turbines.

Wind power

Already back in the seventies private experiments were made with wind power in the Faroe Islands. As strange as it sounds, wind power poses an array of complex predicaments in the islands where there otherwise is no shortage of wind. The problem consists in the constantly changing wind speed - from gentle breezes to winds of hurricane strength, combined with violent gusts of wind caused by the rugged topography of the land. This calls for robust wind turbines and levelling techniques to match the surroundings.

In 1993 SEV erected a wind turbine in Neshagi in the south of Eysturoy. In 2003 the company made an agreement with the privately owned company "Røkt" to buy electric power from the company's three wind turbines at Vestmanna.

Two years later, in 2005, SEV erected three more wind turbines in Neshagi on a trial basis. These turbines were huge and could be seen from far and wide - immediately earning the place the colloquial nickname "Calvary". During a hurricane at the turn of 2011/12, two of these mills were destroyed. The third one was taken down, and in 2012 two new wind turbines were erected at the site, as well as three more, further south in the area. These new turbines are equipped with features that can withstand very high winds and produce energy in wind forces reaching up to 34 meters per second.

In 2014 the wind energy sector gained additional capacity when SEV’s Húsahagi wind farm came officially online with 13 large wind turbines. Experiments are also made with battery capacities designed to reduce irregularities in wind energy supply. Technological progress has led to a greater yield of wind energy in the total energy production.

In 2015 renewable energy sources, hydro- and wind power, constituted 60% of the total energy production in the Faroe Islands - while the remaining 40% is based on fossil fuels. A 2014 study of energy production countries revealed that of all countries which do not have natural energy sources (as for example Iceland with its hot springs), Denmark was at the top of the list with a green energy production of 40%, followed by Germany with approximately 30%. That same year the Faroe Islands, which were not included in the study, had a hydro- and wind power production of 51%, which is significantly higher than that of Denmark and Germany. In just one year, an additional 10% was added to the production.

According to power producer SEV, the goal is that renewable energy production will reach 100% in 2030.

Renewable energy is on everyone's mind these days. There are definite limits to the earth's fossil fuel resources. Oil and coal-fired power plants are contributing excessively to the total CO2 emissions, already affecting the global climate to such an extent that we now are able to physically measure the negative consequences. Then there is the unsettling conclusion of Murphy's Law stating that "anything that can go wrong, will go wrong" – something that repeatedly has been confirmed by the otherwise efficient nuclear power plants.

In the Faroe Islands it was the topography of the country, the steep mountain sides and the vast amounts of rain, which from the very beginning spurred the interest in renewable energy.

The pioneer

Already back in 1907, Ólavur á Heygum, a farmer and a businessman, attempted to have a hydroelectric plant built in his hometown of Vestmanna. He had an idea of stemming the precipitous river Fossá, conducting the water down to a turbine located on the shore. Ólavur started a simple damming of the river, but lack of interest and funding meant that the project had to be abandoned. Until his dying day in 1923 Ólavur tried to win support for his plans, but political bickering and personal bankruptcy due to his idealistic undertakings, put an effective end to his pioneering efforts.

In Botn

Instead, it was due to efforts by insightful local businessmen and the municipal council in Vágur in Suðuroy that the first hydroelectric plant in the Faroes was built. By damming up two mountain lakes in the mountains north of the village and conducting the water in pipes down to the turbines at the base of the steep valley "in Botn" on the west coast, an efficient power plant eventually started producing electricity for the entire island. The hydropower plant was commissioned in 1921 and is still operative.

In the same year that the hydroelectric power plant "in Botn" started producing electricity, an engine power plant was commissioned in Torshavn, where topographic conditions for hydroelectric plants are non-existent. In 1931 a hydroelectric power plant started operating "Norðuri á Strond", close to the booming fishing town of Klaksvík on Borðoy island. In the years that followed small and major water and engine power plants began operation in various locations – but it was not until after the Second World War that efforts were made to coordinate an effective production of electric power.

SEV

In 1946 19 municipalities in the centrally located islands of Streymoy, Eysturoy and Vágar, founded a public electric production company named SEV. The company was tasked to coordinate and fund a joint effort in electric power production and in 1951 a large-scale project was initiated with the aim of realizing Ólavur á Heygum's vision of a hydropower plant in Vestmanna. Dams were built in mountain creeks and the water was channelled in pipes down to a power station on the banks of the river Fossá. On May 5th 1954, the Fossá power plant became operative. In a period of nine years following the Fossá project, two more hydroelectric plants were built at Vestmanna.

In 1963 power production capacities across the country were transferred to SEV, power producer and distributor. Consequently SEV assumed control over the local hydro- and engine plants. The distribution network was streamlined and smaller engine power plants around the islands were taken out of service.

Throughout the sixties energy needs in the Faroes increased constantly, especially in the central regions. It was therefore decided to build a power plant operating on crude oil in the Sund region north of Tórshavn. In 1975, two large machines in the Sund power plant became operative. The plant was further expanded in the late seventies and early eighties and now comprises five machines. Functioning mainly as a backup the Sund power plant is capable of supplying the entire Faroe Islands with electric power if, for some reason, the rest of the plants should become inoperative.

The Eiði Hydropower Plant

The Sund power plant turned out to be an expensive affair even before it was finished. The oil crises in the early and late seventies opened the eyes of the decision-makers to the fact that renewable energy was the way forward. A decision was made to further expand hydropower plants - this time exploiting major water resources in a mountain lake called Eiðisvatn, south of the village of Eiði in Eysturoy.

The project called for the construction of a power plant and dam to increase the capacity of Eiðisvatn. In addition, tunnels were drilled in several phases to rivers in the area. The first turbine in the Eiði power plant became operative in 1987, and in 2014 the power plant was finally finished with the installation of three powerful turbines.

Wind power

Already back in the seventies private experiments were made with wind power in the Faroe Islands. As strange as it sounds, wind power poses an array of complex predicaments in the islands where there otherwise is no shortage of wind. The problem consists in the constantly changing wind speed - from gentle breezes to winds of hurricane strength, combined with violent gusts of wind caused by the rugged topography of the land. This calls for robust wind turbines and levelling techniques to match the surroundings.

In 1993 SEV erected a wind turbine in Neshagi in the south of Eysturoy. In 2003 the company made an agreement with the privately owned company "Røkt" to buy electric power from the company's three wind turbines at Vestmanna.

Two years later, in 2005, SEV erected three more wind turbines in Neshagi on a trial basis. These turbines were huge and could be seen from far and wide - immediately earning the place the colloquial nickname "Calvary". During a hurricane at the turn of 2011/12, two of these mills were destroyed. The third one was taken down, and in 2012 two new wind turbines were erected at the site, as well as three more, further south in the area. These new turbines are equipped with features that can withstand very high winds and produce energy in wind forces reaching up to 34 meters per second.

In 2014 the wind energy sector gained additional capacity when SEV’s Húsahagi wind farm came officially online with 13 large wind turbines. Experiments are also made with battery capacities designed to reduce irregularities in wind energy supply. Technological progress has led to a greater yield of wind energy in the total energy production.

In 2015 renewable energy sources, hydro- and wind power, constituted 60% of the total energy production in the Faroe Islands - while the remaining 40% is based on fossil fuels. A 2014 study of energy production countries revealed that of all countries which do not have natural energy sources (as for example Iceland with its hot springs), Denmark was at the top of the list with a green energy production of 40%, followed by Germany with approximately 30%. That same year the Faroe Islands, which were not included in the study, had a hydro- and wind power production of 51%, which is significantly higher than that of Denmark and Germany. In just one year, an additional 10% was added to the production.

According to power producer SEV, the goal is that renewable energy production will reach 100% in 2030.

Seasons

(Sepac 2016)

Date Of Issue 22.02.2016

(Sepac 2016)

Date Of Issue 22.02.2016

Seasons

One day when my soul was so tired and sad,

I walked towards the shore in the west

Then I heard your ”klip”, this familiar sound

You most beloved summer guest...

Winter storms, drizzle and sleet, the ocean's relentless hammering on the coast and - the almost permanent winter darkness. Although the merciful Gulf Stream guarantees relatively mild winters, temperature wise, here in the North Atlantic and we rarely suffer from extreme cold, winter is a tough time of year to go through. Rain, snow and hail, combined with winter darkness and the harsh Atlantic gales, can faze even the strongest.

It is therefore no wonder that the Faroese rural dean, nationalist and poet, Jákup Dahl (1878 - 1944), probably on a stroll in the hometown Vágur, was torn out of his depression by the sound of the oystercatcher's calling - and inspired to write one of the most beloved Faroese songs: "Tjaldur, ver vælkomið" - a welcome hymn to the Faroese national bird, the oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus).

As a matter of fact, spring in the Faroe Islands is heralded, even before it physically manifests, by the arrival of the oystercatchers, from wintering in the British Isles and the French Atlantic coast. The symbolic significance of this particular bird's arrival is not only a cultural condition – the oystercatcher's first call, the characteristic “klip, klip,” also affects the instincts, the unconscious computer, which detects and combines the small signs of oncoming changes. Just like the arrival of the first lams, a couple of months later, the first calling of the oystercatcher is something that people notice and talk about.

So, although the stormy winter season is not over yet, Saint Gregory's Day on the 12th of March is celebrated for the arrival of the oystercatcher and the oncoming spring. All over the country, scouts march, people gather at public meetings and listen to speeches about springtime – and sing Dahl's popular song about the beloved summer visitor.

The next couple of months, the spirit of winter gradually fades out from the rugged landscape. Just nine days after Saint Gregory's Day, Spring Equinox appears and the light hours start to accelerate, until they at summer solstice are so dominant, that night is reduced to a vague shadow of itself. The colours of the islands shift from the khaki yellow winter costume, into an orgy of green. Alongside the countless streams in the meadows, broad yellow belts of marsh marigold (Caltha palustris L) appear – the national flower, which the Faroese love almost as much as the oystercatcher.

It is high summer, and nature exploits the long daylight to its extent. In the outback, sheep and lams are grazing, while the oystercatcher and other birds of the outback are busy hatching and feeding their young. Down in the meadows, the faint breeze makes waves in the juicy grass, while eider ducks and their hardy ducklings gently float in lazy waves in fiords and straits. A surprised tourist may stop on a path, puzzled by the sound of playing children at eleven o'clock in the evening – a pretty common occurrence in the Faroese summer. And generally sounds are carried wide and far in the bright evening hours, when the noise from man's daily work has subsided. The cry of the seabirds, wading birds calls and warnings and the smaller birds song in gardens and meadows. This is the happy season, the children's season, the festival season.

After the last town festival, the national festival Ólavsøka, in late July, comes the next major change in the cultural landscape. Farmers and smallholders have to secure the winter feed for sheep and cattle, and begin to harvest hay in the meadows. Slowly but surely bright rectangles appear on the slopes, until the meadows finally resemble an oversized patchwork. The landscape loses its fresh green color - and out of the Atlantic, the first low-pressure storms come rolling toward the islands. The urban gardens change color as shrubs and trees first turn yellow and then red and brownish - autumn has arrived and nature slowly shuts down.

In September the oystercatchers start to congregate in large flocks on the beach - and in the middle of the month, the first birds take off and start the long journey to the British Isles and the Atlantic coast of France.

This is the melancholic season, the beginning of winter, when people see the last oystercatchers migrate southeast. Ahead lies stormy months with rain, sleet and snow.

But that is the price for living on these beautiful but rugged islands. And we pay it without complaint, knowing that sooner or later, the oystercatcher's “klip, klip”, again will herald the coming of spring.

One day when my soul was so tired and sad,

I walked towards the shore in the west

Then I heard your ”klip”, this familiar sound

You most beloved summer guest...

Winter storms, drizzle and sleet, the ocean's relentless hammering on the coast and - the almost permanent winter darkness. Although the merciful Gulf Stream guarantees relatively mild winters, temperature wise, here in the North Atlantic and we rarely suffer from extreme cold, winter is a tough time of year to go through. Rain, snow and hail, combined with winter darkness and the harsh Atlantic gales, can faze even the strongest.

It is therefore no wonder that the Faroese rural dean, nationalist and poet, Jákup Dahl (1878 - 1944), probably on a stroll in the hometown Vágur, was torn out of his depression by the sound of the oystercatcher's calling - and inspired to write one of the most beloved Faroese songs: "Tjaldur, ver vælkomið" - a welcome hymn to the Faroese national bird, the oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus).

As a matter of fact, spring in the Faroe Islands is heralded, even before it physically manifests, by the arrival of the oystercatchers, from wintering in the British Isles and the French Atlantic coast. The symbolic significance of this particular bird's arrival is not only a cultural condition – the oystercatcher's first call, the characteristic “klip, klip,” also affects the instincts, the unconscious computer, which detects and combines the small signs of oncoming changes. Just like the arrival of the first lams, a couple of months later, the first calling of the oystercatcher is something that people notice and talk about.

So, although the stormy winter season is not over yet, Saint Gregory's Day on the 12th of March is celebrated for the arrival of the oystercatcher and the oncoming spring. All over the country, scouts march, people gather at public meetings and listen to speeches about springtime – and sing Dahl's popular song about the beloved summer visitor.

The next couple of months, the spirit of winter gradually fades out from the rugged landscape. Just nine days after Saint Gregory's Day, Spring Equinox appears and the light hours start to accelerate, until they at summer solstice are so dominant, that night is reduced to a vague shadow of itself. The colours of the islands shift from the khaki yellow winter costume, into an orgy of green. Alongside the countless streams in the meadows, broad yellow belts of marsh marigold (Caltha palustris L) appear – the national flower, which the Faroese love almost as much as the oystercatcher.

It is high summer, and nature exploits the long daylight to its extent. In the outback, sheep and lams are grazing, while the oystercatcher and other birds of the outback are busy hatching and feeding their young. Down in the meadows, the faint breeze makes waves in the juicy grass, while eider ducks and their hardy ducklings gently float in lazy waves in fiords and straits. A surprised tourist may stop on a path, puzzled by the sound of playing children at eleven o'clock in the evening – a pretty common occurrence in the Faroese summer. And generally sounds are carried wide and far in the bright evening hours, when the noise from man's daily work has subsided. The cry of the seabirds, wading birds calls and warnings and the smaller birds song in gardens and meadows. This is the happy season, the children's season, the festival season.

After the last town festival, the national festival Ólavsøka, in late July, comes the next major change in the cultural landscape. Farmers and smallholders have to secure the winter feed for sheep and cattle, and begin to harvest hay in the meadows. Slowly but surely bright rectangles appear on the slopes, until the meadows finally resemble an oversized patchwork. The landscape loses its fresh green color - and out of the Atlantic, the first low-pressure storms come rolling toward the islands. The urban gardens change color as shrubs and trees first turn yellow and then red and brownish - autumn has arrived and nature slowly shuts down.

In September the oystercatchers start to congregate in large flocks on the beach - and in the middle of the month, the first birds take off and start the long journey to the British Isles and the Atlantic coast of France.

This is the melancholic season, the beginning of winter, when people see the last oystercatchers migrate southeast. Ahead lies stormy months with rain, sleet and snow.

But that is the price for living on these beautiful but rugged islands. And we pay it without complaint, knowing that sooner or later, the oystercatcher's “klip, klip”, again will herald the coming of spring.