2010

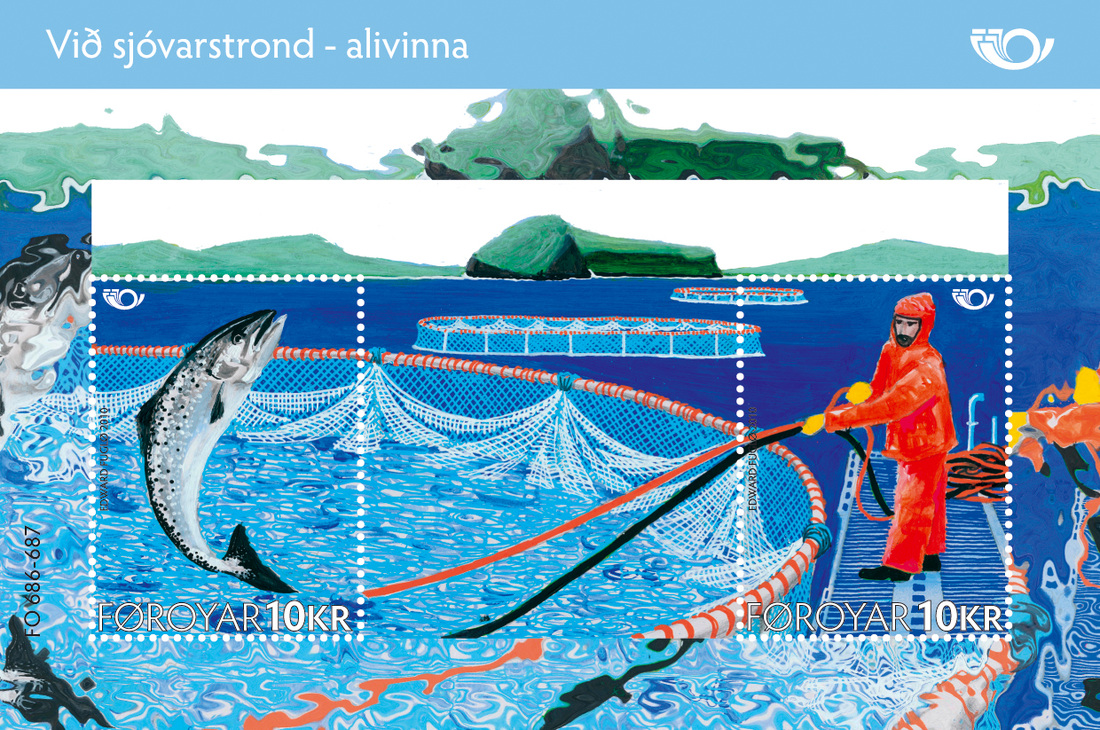

On The Seacoast – Aquaculture

Date Of Issue 24.03.2010

Date Of Issue 24.03.2010

Aquaculture is "farming", fishing is "hunting". Each of these two lifestyles represents its own social system and basic culture. We can recognise them even in the oldest known cultures. Societies that live by farming want to control nature by sowing, cultivating and reaping crops, whereas societies that live by hunting are unable to control nature and are obliged to adapt to it: people must follow the animals they hunt. But people are likely to be healthiest when they eat both meat and plants, so each type of society kept an eye on the other's way of life. The primitive societies that were based on hunting got their vegetable diet from plants that were collected where they were found by chance. Small animals were also hunted in the ancient agricultural societies, but their social systems were not organised around hunting.

Faroese society combined farming and fishing from the earliest times up to the second half of the 19th century. The people of the Faroes lived by farming and by catching fish, birds and whales. Then hunting developed to a greater extent than did farming, which almost disappeared. This development continued until about 40 years ago when a completely new type of farming arose: aquaculture.

Aqua culturists are the farmers of the sea. They do not catch fish as hunters do. Aquaculture has become the second-biggest business in the Faroes and will have superseded traditional fishing in a few years – depending on whether this is calculated by volume or turnover.

Aquaculture depends on modern technology and up-to-date research to a considerable extent and has therefore never before been possible. But the social system is the same as we are familiar with from ancient times: people want to control nature and adapt it to enable them to create permanent settlements. And even though modern fishing is also dependent on the latest technology and research, in principle it follows the time-honoured pattern of the hunter-gatherer society in that it follows the animals it hunts.

At times, fishing approaches its ultimate limits where quotas are concerned and aquaculture has also had a number of dramatic reverses when nature imposed its own limits through disease and mortality, for instance. Nevertheless, both occupations have flourished in recent years so that the combination of social systems than can be observed in the Faroes at present is rather reminiscent of the ancient social system, with the difference that we now "cultivate" fish rather than plants.

Eyðun Andreasen Aquaculture The clean, warm seas around the Faeroes are ideal for farming salmon. Initially, in the 1970s, rainbow trout were farmed but since then the industry has concentrated on farming salmon. Today there are about 25 fish farms in the fjords and straits around the islands and salmon farming accounts for almost one-third of total exports from the Faroes.

Faroese society combined farming and fishing from the earliest times up to the second half of the 19th century. The people of the Faroes lived by farming and by catching fish, birds and whales. Then hunting developed to a greater extent than did farming, which almost disappeared. This development continued until about 40 years ago when a completely new type of farming arose: aquaculture.

Aqua culturists are the farmers of the sea. They do not catch fish as hunters do. Aquaculture has become the second-biggest business in the Faroes and will have superseded traditional fishing in a few years – depending on whether this is calculated by volume or turnover.

Aquaculture depends on modern technology and up-to-date research to a considerable extent and has therefore never before been possible. But the social system is the same as we are familiar with from ancient times: people want to control nature and adapt it to enable them to create permanent settlements. And even though modern fishing is also dependent on the latest technology and research, in principle it follows the time-honoured pattern of the hunter-gatherer society in that it follows the animals it hunts.

At times, fishing approaches its ultimate limits where quotas are concerned and aquaculture has also had a number of dramatic reverses when nature imposed its own limits through disease and mortality, for instance. Nevertheless, both occupations have flourished in recent years so that the combination of social systems than can be observed in the Faroes at present is rather reminiscent of the ancient social system, with the difference that we now "cultivate" fish rather than plants.

Eyðun Andreasen Aquaculture The clean, warm seas around the Faeroes are ideal for farming salmon. Initially, in the 1970s, rainbow trout were farmed but since then the industry has concentrated on farming salmon. Today there are about 25 fish farms in the fjords and straits around the islands and salmon farming accounts for almost one-third of total exports from the Faroes.

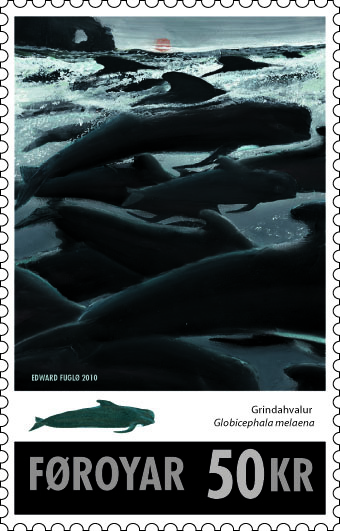

Long-finned Pilot Whale

Date Of Issue 22.02.2010

Date Of Issue 22.02.2010

The only terrestrial mammals on the Faroes are a few small rodents. Therefore, the only mammals that have been hunted regularly are seals, to be found in abundance along the coast. One exception is the hare, but it was introduced onto the islands in the 19th century. The capture of pilot whales is not hunting in the true sense of the word. They are not hunted. They are driven ashore when a pod happens to swim by.

On the Faroes there has always been free access to the resources of the sea. This also applies to pilot whales. On the other hand, catching them requires extensive social organisation. On account of the topography of the islands, there are only a few places where it is possible to drive a pod of whales ashore and slaughter them. Since 1832, legislation has governed where pilot whales may be caught. There were probably also rules on this earlier. However, the legislation does not give the inhabitants of a village with a specified catch site a preferential right to catch the whales. The meat and blubber of pilot whales is equally distributed among all inhabitants, whether newborn or elderly. Even visitors get their lawful share. For practical reasons, the country is divided into pilot whale districts, but over time there will be food for all. In this way, a unique distribution system has emerged in connection with the exploitation of this important resource.

Everyone is entitled to participate in the catch. However, it has not been common to have women in the boats as the Faroese were previously very superstitious about women at sea. Things are probably different now. There have been no gender differences in connection with the distribution of the catch.

Some foreigners have often been fascinated by the capture of pilot whales in the Faroes. These include the Danish official Chr. Pløyen, who composed the poem Grindevise in 1832. This enthusiastic poem of homage is in the style of a traditional ballad and has been in common use for the traditional pilot whale dance, a chain dance, often outdoors after a successful catch while people waited for distribution by the sheriff, celebrated the catch and needed to keep warm. The pilot whale dance is hardly danced any more.

In this way, the capture of pilot whales has also assumed a visible position in cultural life. A number of Faroese poets have also written about the capture of pilot whales in their poetry, in particular patriotic and regional poetry. These include Hans Andreas Djurhuus, Mikkjal á Ryggi and Jóannes Patursson.

In pictorial art, the capture of pilot whales has assumed an almost iconic position via the works of the well-known painter Sámal Joensen-Mikines. The slaughter of pilot whales is one of his main motifs and his works in this genre are among those that have made him best known. In recent years, there has been occasionally severe international criticism of the traditional capture of pilot whales. The method of capture is criticised as being cruel to the animals and it is alleged that pilot whales are an endangered species. The Faroese maintain that, as the annual catch only represents just over 0.01% of the total population, it can hardly be said that they are under threat of extinction. On the other hand, significant improvements have been made to the method of slaughter. It is strictly monitored and governed by detailed rules to eliminate animal suffering.

The Faroese have kept to their traditional capture of pilot whales despite the criticism and most still greatly appreciate a good meal of pilot whale meat and blubber. However, there is some indication that the youngest generation do not fully share their parents’ taste, so we may find that the conflict between time-honoured tradition and modern philosophy of nature will be resolved entirely of its own accord in the not too distant future.

Eyðun Andreasen, Professor

On the Faroes there has always been free access to the resources of the sea. This also applies to pilot whales. On the other hand, catching them requires extensive social organisation. On account of the topography of the islands, there are only a few places where it is possible to drive a pod of whales ashore and slaughter them. Since 1832, legislation has governed where pilot whales may be caught. There were probably also rules on this earlier. However, the legislation does not give the inhabitants of a village with a specified catch site a preferential right to catch the whales. The meat and blubber of pilot whales is equally distributed among all inhabitants, whether newborn or elderly. Even visitors get their lawful share. For practical reasons, the country is divided into pilot whale districts, but over time there will be food for all. In this way, a unique distribution system has emerged in connection with the exploitation of this important resource.

Everyone is entitled to participate in the catch. However, it has not been common to have women in the boats as the Faroese were previously very superstitious about women at sea. Things are probably different now. There have been no gender differences in connection with the distribution of the catch.

Some foreigners have often been fascinated by the capture of pilot whales in the Faroes. These include the Danish official Chr. Pløyen, who composed the poem Grindevise in 1832. This enthusiastic poem of homage is in the style of a traditional ballad and has been in common use for the traditional pilot whale dance, a chain dance, often outdoors after a successful catch while people waited for distribution by the sheriff, celebrated the catch and needed to keep warm. The pilot whale dance is hardly danced any more.

In this way, the capture of pilot whales has also assumed a visible position in cultural life. A number of Faroese poets have also written about the capture of pilot whales in their poetry, in particular patriotic and regional poetry. These include Hans Andreas Djurhuus, Mikkjal á Ryggi and Jóannes Patursson.

In pictorial art, the capture of pilot whales has assumed an almost iconic position via the works of the well-known painter Sámal Joensen-Mikines. The slaughter of pilot whales is one of his main motifs and his works in this genre are among those that have made him best known. In recent years, there has been occasionally severe international criticism of the traditional capture of pilot whales. The method of capture is criticised as being cruel to the animals and it is alleged that pilot whales are an endangered species. The Faroese maintain that, as the annual catch only represents just over 0.01% of the total population, it can hardly be said that they are under threat of extinction. On the other hand, significant improvements have been made to the method of slaughter. It is strictly monitored and governed by detailed rules to eliminate animal suffering.

The Faroese have kept to their traditional capture of pilot whales despite the criticism and most still greatly appreciate a good meal of pilot whale meat and blubber. However, there is some indication that the youngest generation do not fully share their parents’ taste, so we may find that the conflict between time-honoured tradition and modern philosophy of nature will be resolved entirely of its own accord in the not too distant future.

Eyðun Andreasen, Professor

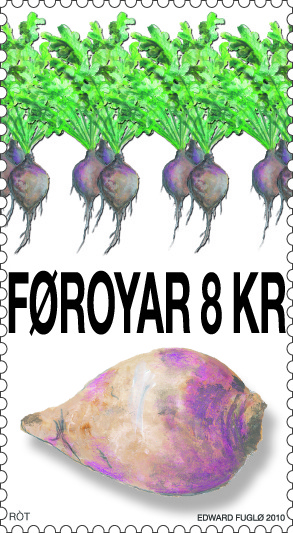

Potatoes and root vegetables

Date Of Issue 20.09.2010

Date Of Issue 20.09.2010

Root vegetables are an old food on the Faroe Islands and much older that potatoes, which did not become common until the mid-19th century. Two types of root vegetable were grown: Faroese turnips (Brassica napus) and Norwegian turnips (Brassica rapa), which used to be commonest. Faroese turnips grew down into the soil, so far down that a spade was needed to dig them up, whereas Norwegian turnips grew close to the surface and were easy to pick by hand. The place where root vegetables were grown was called the rótakál. Root vegetables were mainly used for soup, but also for bread, as well as being cooked for dinner together with poultry, for example.

Later on the Faroe Islanders also started growing other root vegetables such as kohlrabi, different turnip varieties and carrots, as the seeds were now available in the shops. From around 1920 there was a growing interest in kitchen gardens among the population, and people began cultivating various sorts of greens in addition to root vegetables. Before the arrival of potatoes, only root vegetables were served with dinner.

For one reason or another stealing root vegetables used to be very common. Therefore, people who grew root vegetables often tried to hide them by planting them among their potatoes so that the potato shoots would conceal the shoots of their root vegetables.

Kohlrabi, which is often called Faeroese turnip, is now available in the shops. It comes from foreign seed cultivated in the Faroe Islands, but the conditions mean that it does not grow as big and so has a much better flavour.

Potatoes made their first appearance in Denmark in 1719. As far as the Faroe Islands are concerned, we know that root vegetables were being grown in Torshavn in 1775 and 1799, but it was not until the mid-19th century that it became common to grow potatoes. Many people on the islands can remember Hans Marius Debes's story about the first potatoes arriving in Gjógv in 1835.

To begin with potatoes were cultivated in the same way as cereals and root vegetables, but people soon started earthing them up. They used a mattock or shovel to dig a furrow a foot deep, put fertiliser in the bottom and then planted the potatoes in it before creating a ridge. On Mykines it was long thought that potatoes could only be grown in the infield close to the village, where the weather was particularly good. This spot was called the Land of Canaan. No one tried growing them anywhere else and people who did not own land there ate more root vegetables than potatoes. This changed when people started growing turf, as it turned out that potatoes could actually be cultivated everywhere.

Some places were particularly well suited to earthing up potatoes, however, including Oyran in Sørvágur and the beach in Sandur, where earthing-up continued. The same piece of land was often cultivated every year, with cow manure or artificial fertiliser being used to enrich the soil.

The beach was so deep that it was possible to keep potatoes in what was called a potato pit until well into the spring. People would dig a square hole that was deep enough to be frost-free. To enable them to find the potato pit again, they drew a map of the piece of land and marked the pit. The potato pit did the same job as the turf potato clamps, which were more or less buried in the ground. Some people also kept potatoes in their cellars, but it had to be cool enough or the potatoes would start to sprout prematurely.

Potato cultivation on the Faroe Islands only really got going after a man from Miðvágur on Vágar discovered a new growing method. The potatoes were grown under turf that had been turned upside down, i.e. with the grass facing down. This method of growing potatoes was also called Vágaveltan. It was a very easy way to grow potatoes. They were placed on a narrow strip of grass, then the turf was laid on top, grass to grass, with the soil facing up. This is now the commonest method of growing potatoes, with just a single handful of artificial fertiliser being used between each potato plant.

After 1925, and in the lean thirties in particular, potatoes became very important in Faroese households and dinner was not dinner unless it included potatoes.

So many potatoes were grown in some villages that they could be sold to other villages, which is what happened in Sandur, among other places. In the village of Tvøroyri, for example, there were many people who did not own land and so had no choice but to buy potatoes. These days most people buy imported potatoes in the shops because it is easier, but many people still enjoy growing their own potatoes, which taste much better than the shop-bought variety of course.

Jóan Pauli Joensen , Professor

Later on the Faroe Islanders also started growing other root vegetables such as kohlrabi, different turnip varieties and carrots, as the seeds were now available in the shops. From around 1920 there was a growing interest in kitchen gardens among the population, and people began cultivating various sorts of greens in addition to root vegetables. Before the arrival of potatoes, only root vegetables were served with dinner.

For one reason or another stealing root vegetables used to be very common. Therefore, people who grew root vegetables often tried to hide them by planting them among their potatoes so that the potato shoots would conceal the shoots of their root vegetables.

Kohlrabi, which is often called Faeroese turnip, is now available in the shops. It comes from foreign seed cultivated in the Faroe Islands, but the conditions mean that it does not grow as big and so has a much better flavour.

Potatoes made their first appearance in Denmark in 1719. As far as the Faroe Islands are concerned, we know that root vegetables were being grown in Torshavn in 1775 and 1799, but it was not until the mid-19th century that it became common to grow potatoes. Many people on the islands can remember Hans Marius Debes's story about the first potatoes arriving in Gjógv in 1835.

To begin with potatoes were cultivated in the same way as cereals and root vegetables, but people soon started earthing them up. They used a mattock or shovel to dig a furrow a foot deep, put fertiliser in the bottom and then planted the potatoes in it before creating a ridge. On Mykines it was long thought that potatoes could only be grown in the infield close to the village, where the weather was particularly good. This spot was called the Land of Canaan. No one tried growing them anywhere else and people who did not own land there ate more root vegetables than potatoes. This changed when people started growing turf, as it turned out that potatoes could actually be cultivated everywhere.

Some places were particularly well suited to earthing up potatoes, however, including Oyran in Sørvágur and the beach in Sandur, where earthing-up continued. The same piece of land was often cultivated every year, with cow manure or artificial fertiliser being used to enrich the soil.

The beach was so deep that it was possible to keep potatoes in what was called a potato pit until well into the spring. People would dig a square hole that was deep enough to be frost-free. To enable them to find the potato pit again, they drew a map of the piece of land and marked the pit. The potato pit did the same job as the turf potato clamps, which were more or less buried in the ground. Some people also kept potatoes in their cellars, but it had to be cool enough or the potatoes would start to sprout prematurely.

Potato cultivation on the Faroe Islands only really got going after a man from Miðvágur on Vágar discovered a new growing method. The potatoes were grown under turf that had been turned upside down, i.e. with the grass facing down. This method of growing potatoes was also called Vágaveltan. It was a very easy way to grow potatoes. They were placed on a narrow strip of grass, then the turf was laid on top, grass to grass, with the soil facing up. This is now the commonest method of growing potatoes, with just a single handful of artificial fertiliser being used between each potato plant.

After 1925, and in the lean thirties in particular, potatoes became very important in Faroese households and dinner was not dinner unless it included potatoes.

So many potatoes were grown in some villages that they could be sold to other villages, which is what happened in Sandur, among other places. In the village of Tvøroyri, for example, there were many people who did not own land and so had no choice but to buy potatoes. These days most people buy imported potatoes in the shops because it is easier, but many people still enjoy growing their own potatoes, which taste much better than the shop-bought variety of course.

Jóan Pauli Joensen , Professor

All Issues Copyright Posta, www.stamps.fo